Inside the soldiers’ resistance

Independent journalist documented the day-to-day brutality of life under U.S. occupation in a way no mainstream media sources did in his 2007 book Beyond the Green Zone: Dispatches from an Unembedded Journalist in Occupied Iraq.

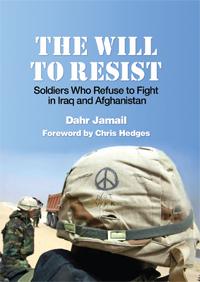

In his new book, The Will to Resist: Soldiers Who Refuse to Fight in Iraq and Afghanistan, Jamail looks inside the resistance developing within the American military.

This is the first comprehensive look at dissent within the ranks of world's most powerful military, documenting the fight for justice inside the belly of the beast. Below, we reprint the Introduction to The Will to Resist.

AS AN independent reporter working at different points during the first six years of the occupation of Iraq, I had some of the most disturbing experiences of my life. The U.S. military, which I had been raised to admire, had for me morphed into the enemy. Reporting from the Iraqi perspective on a brutal, chaotic, violent occupation that was destroying millions of lives with the indiscriminate randomness of a hurricane, my sense of outrage had transformed into an anger that I often aimed at those same soldiers I had admired as a child.

This feeling of being violated and betrayed increased with my continued coverage of widespread military operations; the use of white phosphorous against civilians in Fallujah; the collective punishment of entire cities by cutting off their water, electricity, and medical supplies; the widely prevalent torture of Iraqis; and ongoing home raids. To date, the occupation has managed to displace one out of every six Iraqis from their homes, and has, directly or indirectly, killed more than 1.2 million people.

I felt a solidarity with the Iraqis because I had no difficulty imagining how I would feel if my country had been invaded and occupied. My direct experience of this extremely unethical behavior, very common among those in the U.S. military in Iraq, and my rage at the heedless and deliberate devastation I saw them wreak upon the people of Iraq, fueled my rage and transformed my childhood heroes into beasts. I was dehumanized by the occupation.

On returning home, in the course of delivering lectures and presenting slideshows and providing testimony at various forums, I started to meet soldiers who had deployed to Iraq. As I got to know them, I was surprised to discover within them a familiar anguish. I found the same survivor guilt, the ongoing burden of living a normal life without while carrying the knowledge within that Iraq is burning and her people are struggling to survive on a daily basis. I could see in their eyes the same angst that I felt--the utter inability to reconcile what we had seen in Iraq with the fact of our own relatively secure existence in a country whose government was responsible for causing irreparable damage there.

This compelled me to dig deeper. I realized a desire to meet more of these veterans who had been placed in an untenable situation and examine the roots and implications of their resistance to what was happening in Iraq. Through conversations, I learned quickly that there was active resistance within the ranks to what the troops were being ordered to do in Iraq.

I found men and women to interview who had spent time in Iraq doing patrols, working on bases, running supply convoys, and even acting as snipers. Others worked as intelligence operatives gathering information by spying on cell phone conversations. Along the way, talking with these men and women, I realized the bond I shared with them had become, in many ways, as strong as my bond with the Iraqis I interviewed abroad, a bond that inspires me to risk my life to work there time and time again.

WHILE THERE is a widespread, mostly subterranean resistance movement in the military today, admittedly it is not yet nearly on the scale of that which played a critical role in bringing an end to the Vietnam War. More than ever, due to the faltering U.S. economy, people are joining or staying in the military because of financial necessity, despite the risks this decision entails.

In fall 2008, I spoke with David Cortright, a Vietnam War veteran who has served as consultant or adviser to agencies of the United Nations, international think tanks, and the foreign ministries of Canada, Japan, and several European countries. He has authored 16 books, including Soldiers in Revolt (Haymarket Books, 2005), which is about the massive GI resistance movement against the Vietnam War. I was interested to know how he viewed the growing resistance movement in the military today. Cortright said he feels soldiers are not being as overt today when speaking out against what is happening to the military because "there is much more to lose now by being punished by the brass. I see that as the most fundamental change--the nature of the military today as an all-volunteer force, economic conscription."

Another factor that serves to dampen GI resistance today is that nearly 50 percent of those serving are married, and many of them have children to support. This, according to Cortright, constricts the nature and scope of the movement. Another key difference between Vietnam and current-era GIs, he feels, is that today when someone joins the military, they tend to stay with their unit for their career. "Now there is much emphasis on unit loyalty and solidarity. You bond with these people, and these social horizontal linkages have an effect of binding people to each other within the military community...I talk with lots of guys who hate the war, yet they go back for a second or third tour out of their duty to support their fellow soldiers. They think they are helping their buddies." That has been my experience, too. I have had occasion to speak with veterans and active-duty soldiers totally opposed to the occupation who nevertheless agree to redeploy for the sake of their "buddies."

Cortright also underscores the lack of substantial civilian support as a reason for today's GI antiwar movement not being on par with the Vietnam-era movement. "During Vietnam there wasn't a real GI movement until 1968, so it took a few years, but that was supported by civilians who made enormous sacrifices to help them. At the time we had a couple of legal defense organizations set up to defend GIs which don't exist today. Then we had groups like the Young Socialist Alliance, among others, that would back those of us who spoke up in those days--we knew we could get access to lawyers."

However, a network is gradually building up, of groups tasked with helping those in the military who choose to resist. Two such groups, the Military Law Task Force and the Center on Conscience and War, which are both successors to similar groups from the Vietnam era are examples. Cortright is convinced that "though we haven't seen as widespread a phenomenon as during Vietnam," there is no denying that resistance exists and is spreading. "We've also seen individual cases of resistance, and the work that many veterans have done in reaching out to active-duty military personnel has been successful. This is another expression of the underlying sentiment in the military that the war is illegal and unjust."

With each passing day, more soldiers are speaking out against the occupation, and are receiving support from civilians. This was a key component of the resistance during Vietnam, says Cortright. "People in the military have great authority and legitimacy in speaking to the broader public in the political arena, and the more we as civilians can support them in doing this, the more effective they will be in bringing awareness to the movement and the need to end the war."

Of course, times have changed. During Vietnam, there was one main Winter Soldier event--when Vietnam veterans returning from the front lines held a weekend press conference in Detroit on January 31, 1971, to tell the media what was really happening in the war and why it should end immediately. "Winter soldiers" is a reference to what Thomas Paine, America's founding father, called people who stand up for the soul of their country, even in its darkest hours.

Today, we've seen several of these Winter Soldier events, sponsored by a group called Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW). Such events are spreading across the country, as well as internationally. By spring 2009, Winter Soldier events had occurred in Maryland, Washington, Florida, Wisconsin, California, Illinois, New York, Oregon, Texas, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C., and were scheduled for Georgia, as well as Germany.

DURING THE writing of this book, I was consistently and deeply moved and awed by the courage and fortitude of the veterans who were taking a stand, despite the long odds against them and the brute force the military is able to exert upon them for doing so. I learned from them that, as perpetrators, their post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is far more incurable and difficult to treat than that of people like me who had only witnessed the horrors they had been instrumental in inflicting. They have to live with the consciousness of having killed Iraqis, participated in their torture, raided their homes with women sobbing in the background.

Surpassed only by average Iraqis, members of the U.S. military who have been deployed to Iraq are paying the highest price for the occupation--both while in Iraq and when they come back home. They are now part of an unfortunate, tragic segment of U.S. society that has been maligned and tossed aside, neglected, forgotten. Today, more U.S. war veterans are killing themselves than are dying in open combat while overseas. One thousand veterans who are receiving care from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) are attempting suicide every single month, and eighteen veterans kill themselves daily. Not all of these veterans served in Iraq, but what these figures bode for the future is inconceivable, when we consider that 1.7 million soldiers have so far served in the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan.

As if surviving their deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan is not enough, upon their return home, soldiers face another battle--to obtain the services they are entitled to receive from the VA. A valid discharge from the military entitles all soldiers to medical care from the agency. In the six months leading up to March 31, 2008, 1,467 veterans died while waiting to learn whether their disability claims were going to be approved by the government. Veterans who appeal a VA decision to deny a disability claim must wait an average of nearly four and a half years for their answer. As of March 25, 2008, 287,790 war veterans from the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan had filed disability claims with the VA.

These facts partially explain the growing resistance within the military not just against the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, but also against the horrendous toll they are taking on troops, who suffer while they serve there and suffer even more upon returning home. Being virtually abandoned by the government they swore an oath to protect and serve often becomes the proverbial last straw for the veterans, forcing them to resort to suicide.

The deeper one digs, the more apparent it becomes that the military is in a state of near collapse. For years now, one retired general after another has appeared in the media to denounce the occupation of Iraq, and to expose what it is doing to destroy the military. With the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, more than 565,000 troops have been deployed more than once.9By December 2006, it was estimated that 50 percent of troops in Iraq were serving their second tour, and another 25 percent were on their third or fourth tour.

A horrific example of how this is affecting soldiers in Iraq occurred on May 11, 2009, at 2 p.m. Baghdad time, when a U.S. soldier gunned down five fellow soldiers at a stress-counseling center at a U.S. base in Baghdad. Admiral Mike Mullen, the chairman of the U.S. military's Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters at a news conference at the Pentagon that the shootings occurred in a place where "individuals were seeking help." Admiral Mullen added, "It does speak to me, though, about the need for us to redouble our efforts, the concern in terms of dealing with the stress...It also speaks to the issue of multiple deployments."

The military is so overstretched that troops being redeployed often have traumatic brain injury (TBI) from surviving roadside bombs in previous deployments, and more than 43,000 troops listed as medically unfit have been deployed anyway. Soldiers already diagnosed with PTSD and other severely debilitating mental health conditions that accompany it are being redeployed as the military dredges up troops to keep enough boots on the ground in Iraq. By October 2007, the army reported that approximately 12 percent of combat troops in Iraq were coping by taking antidepressants and sleeping pills. By January 2009, the army announced that suicides among U.S. soldiers had risen in the previous year to the highest level in decades. The suicide rate for 2008 was calculated roughly at 20.2 per 100,000 soldiers, which for the first time since the Vietnam War is higher than the adjusted civilian rate.14In addition, more active-duty marines committed suicide in 2008 than in any year since the U.S. invasion of Iraq was launched in 2003, at a rate of 16.8 per 100,000 troops.

Prior to the recent and ongoing collapsing of the U.S. economy, which by raising national unemployment has driven more people to join the military, the armed forces were so short of troops that more than 58,000 troops have been "stop-lossed" since September 11, 2001. Under this policy, soldiers who have fulfilled their contracts are frozen into the military and redeployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Further deepening this crisis, more than a quarter of a million National Guard men and women, who joined the guard to provide aid at home in times of national emergencies such as hurricanes and earthquakes, have been deployed overseas.

Attempting to keep enough boots on the ground for both occupations, on June 22, 2006, the army increased the permissible enlistment age to 42, from a previous limit of 40. This follows a previous rise in the age limit from 35 to 40 in March 2005. By summer 2007, the army had grown so desperate for recruits that it began to recruit indiscriminately in violation of its own criteria. It accepted individuals with health and weight issues, lower academic test scores, and even those with criminal records.

By July 2007, the number of incoming soldiers with prior felony arrests or convictions had more than tripled over the previous five years, and in the first half of 2007, the army had accepted an estimated 8,000 recruits with rap sheets. Former army Private Steve Green is one such example. He was awarded a waiver for previous involvement in criminal activity and was found guilty of raping a 14-year-old Iraqi girl, Abeer Qasim Hamza al-Janabi, and murdering her and three of her family members in the village of Mahmudiyah.

Economics continues to work in favor of the military, assisted in no small measure by its all-out efforts at recruiting. By October 2008, the Army and Marine Corps had spent nearly $640 million in recruitment bonuses. By the end of 2008, the military was once again making its recruiting goals. As unemployment rises, the military lures the desperate offering a sure method of obtaining a paycheck. In addition, the military has resorted to a tried and tested tactic of enticing foreigners into the ranks by offering citizenship after service in the military. For example, on March 3, 2009, 251 U.S. soldiers from 65 countries became U.S. citizens in a ceremony held in one of Saddam Hussein's old palaces in Baghdad. Since 2004, active-duty immigrant soldiers can apply for citizenship without the normal three-year waiting period and without being inside the United States.

THE DRAMATIC change in the political climate of the country following the election of Barack Obama as president, and his promises to bring the troops home, has expectedly caused the population to lose what interest they still retained in Iraq, despite the tardy coverage by the mainstream media. While President Obama promises to bring troops home, he aims to leave behind at least 50,000 as a "residual" and "training" force indefinitely. The end of either occupation definitely does not seem to be in sight.

Most veterans I spoke with while working on this book feel, despite a large section of the populace being opposed to the occupation of Iraq, that the consenting majority in the United States has been complicit in pushing U.S. soldiers into an unsustainable position by not doing enough to end the war. Today antiwar veterans have to muster all the support and resources they can, not only in an attempt to rebuild their lives, but also to affirm and intensify their dual resistance to the ongoing occupation of Iraq and to the inherently dehumanizing nature of the U.S. military system.

I have been impressed by the courage and inspired by the persistence of these veterans. I recognize the risk their resistance entails. Their actions jeopardize benefits they have earned, including health care and funds for college, and can even lead to incarceration.

Working on this book has made me privy to the individual as well as collective transformation that has taken place in a section of the population that is commonly known for its rigidity and subservience to authority. While it was not my initial plan, the voices of resistance in this work have led me to remain more of an observer in the book. By often quoting their words at length, I have attempted to retain the rage, despair, and rawness of their feelings without interjecting my own.

The environment in the United States today is not one that can support and sustain a GI resistance movement of significant proportions, giving it enough power to directly affect the foreign policy of the country, as it did so effectively in the Vietnam era. There is much in the military to prohibit a GI resistance movement from growing anywhere near the proportion that helped end the U.S. war in Vietnam. Military discipline is much more repressive than in the past, which makes organizing more difficult. There is less radicalization of the GI movement, as compared to that in the late 1960s and early 1970s; therefore, passive resistance against the command is more common than direct resistance. There is a much lower level of political awareness and analysis among soldiers as compared to that during Vietnam, when there were hundreds of underground newspapers that served to inform troops while criticizing the military apparatus. The all-volunteer military, rather than a draft, is also responsible for stifling broader dissent.

Despite these factors, dissent in the ranks is happening on a daily basis. While overall violence in Iraq has dropped, it is escalating dramatically in Afghanistan, as President Obama begins to "surge" 30,000 troops into that occupation. The overstretched military is in a state of disrepair, full of demoralized, bitter soldiers whose reasons for staying in are based on economics and loyalty to their friends rather than nationalism or patriotism.

These elements, accompanied by the continuing neglect that soldiers experience upon their return home, are driving larger numbers toward dissent.

This is a book about average soldiers and their brave acts of dissent against a system that is betraying them. I decided to focus on the rank-and-file members who actually served in Iraq, rather than those giving the orders from within safe compounds. I believe it is those who have followed the orders who have had to pay the highest price. My main objective in presenting this book is to highlight the reality that oppressed and oppressors alike suffer the dehumanizing effects of military action. For soldiers and war journalists like myself who have lived with this, struggled with PTSD, and reintegrated ourselves into society, a light at the seemingly endless dark tunnel of the U.S. occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan is the possibility of the shifting of these individual acts of resistance into a broader, organized movement toward justice--both in the military and in U.S. foreign policy.