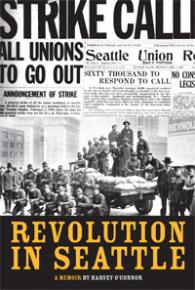

“Labor will feed the people”

Long omitted from the history books, the Seattle General Strike of 1919 offers an inspiring view of what it would look like if workers took power in the U.S. In Revolution in Seattle, newly republished by Haymarket Books, radical journalist and labor historian chronicles the general strike, along with the history of radicalism in the Pacific Northwest that came before it.

O'Connor based this memoir on the accounts of workers and revolutionaries he organized with throughout his life--in addition to radical and union newspapers of the day. As O'Connor, a lifelong radical who was sentenced for contempt for defying the McCarthyite witch-hunt of the 1950s, writes in the foreword, "For many years, I have been increasingly concerned lest one of the most dramatic chapters in the labor history of the United States go unrecorded."

Here, we reprint an excerpt from this classic book.

ON ARMISTICE Day, 1918, the lid blew off the Seattle labor movement. Nearly two years of pent-up frustration were released in a storm of emotion. In that respect, Seattle was no different from the rest of the world. Revolution was the order of the day in Central Europe; the Soviets were battling counterrevolutionaries and Allied intervention; France and Italy were convulsed; in Britain reconstruction of society was the concern of the Labour Party. In the United States, great strikes broke out in steel, focus of industrial feudalism, and in the coalmines and on the railroads. The same pattern was to be repeated after the Second World War.

Foremost cause of the unrest which swept the country was the constantly soaring cost of living, up 50 percent in three years. Wages in the basic industries had been held under governmental control but there were few countervailing controls on prices. Huge shipments of food and supplies were being sent to starving Europe and the shortages resulting in this country led enterprisers to charge all that the traffic would bear. At the same time profits were soaring, too, and it was unbearable to thinking workers that the costs of the war should be piled on them while their employers never had it so good.

In Seattle, the high cost of living was an especially exasperating prod. The Pacific Northwest had always been a high-price region, far off the beaten track of American commerce; costs of transport whether by ship or rail were padded by the extra profits extracted. Even more than in other sections, the Pacific Northwest regarded itself as in a colonial position, exploited by the Eastern captains of industry. The abnormal price situation was exaggerated by the influx of thousands of workers, straining the city's housing and public facilities to the breaking point. Landlords reaped a bonanza by heaping men and families into the scant housing available.

Seattle was exceptional also because of the advanced organization of labor--with a total population of 250,000, there were some 60,000 members in unions, flanked as in few other communities by radical wings of the socialists and IWW. If a speedy reaction to the release of wartime controls on the right to strike were to be found anywhere in the country, it would logically be in Seattle. And that was the fact, proudly reported by Anna Louise Strong just back from the Mooney convention in Chicago. In the Union Record, she wrote that "Seattle is on the map...the place where big constructive ideas come from." She was proud that the Mooney meeting had had its genesis in Seattle.

The 30,000 shipyard workers in the city had been bound by the national A.F. of L. agreement with the War Labor Board which exchanged union recognition for the right to strike in wartime. While the Metal Trades Council held an overall agreement with the yards, neither that Council nor its 21 constituent unions had any final authority in wartime over the wage scales. That authority rested with the Shipbuilding Labor Adjustment Board, usually called the Macy Board, after its chairman, V. Everit Macy. This had been formed by agreement among the U.S. Emergency Fleet Corporation in charge of shipbuilding, the Navy Department, and the international presidents of the unions involved. The Seattle unions complained vehemently that the international unions, in violation of their own constitutions, had taken control over wages from the rank and file.

The Macy Board twice authorized wage increases in 1917. The unions better organized before the war won an average 60 cents a day rise; those representing mainly the unskilled and semi-skilled, much less. The increase for some of around 12.5 percent contrasted with a rise in living costs during the period of 31 percent. The top wage for shipyard laborers was $4.16 a day, or a little under $100 a month. The Board's scales were said to be the minimum but in practice they became the maximum and employers were discouraged from paying more. The Board also tried to equalize wages nationally, which of course was detrimental to the Pacific Northwest, where both wages and prices were traditionally higher than on the East and Gulf coasts.

Immediately after the Armistice, the Metal Trades Council demanded a general wage readjustment. Its president, James A. Taylor, went to Washington to confer with Charles Piez, director of the Emergency Fleet Corporation, and with the Macy Board. When that Board's appeal committee split on the Seattle wage issue, Taylor returned to Seattle confident that he had permission to negotiate directly with the shipyards, provided that wage increases did not increase the price of shipping to the government. A strike vote, preliminary to negotiations, was authorized by the Metal Trades Council in November, 1918, and majorities were received in most unions.

On January 16, 1919, negotiations opened on demands for an $8 scale for mechanics, $7 for specialists, $6 for helpers, and $5.50 for laborers. The Council calculated that its wage demands would leave a profit of $200,000 on each ship, as against the existing $286,000 profit, based on an 8,800-ton ship costing $1,350,000 and sold to the government for $1,636,000. The owners offered increases to the skilled trades but nothing for the unskilled. The skilled trades joined with the mass of the workers in rejecting the splitting tactic.

A WESTERN Union messenger boy helped to precipitate the strike. He bore a telegram addressed to the Metal Trades Association, the employers' body; by mistake he took it to the Metal Trades Council. Its contents were explosive. Director Piez of the Emergency Fleet Corporation had cut through any hope of further negotiation by informing the employers that they would get no more steel if they agreed to any wage increases. Did Piez act on his own initiative, or was it a double-play between him and the companies? Were the unions up against the government as well as the companies? The Metal Trades Council promptly repudiated the agreement, signed illegally, it claimed, by the chiefs of the national unions without consultation or agreement by the local unions.

On January 16, 1919, the Council authorized a strike, to begin January 21. On that day, 30,000 men downed tools, augmented by 15,000 in nearby Tacoma. The yards made no effort to reopen; the unions banned demonstrations, parades, or gatherings, and an unearthly quiet enveloped the yards. To scotch rumors that many of the men were opposed to the strike, Local 104 of the Boilermakers, which comprised nearly half of all strikers, called a meeting to which 6,000 members responded. Dan McKillop, an official, denounced the ship-owners who had taken the credit for the ships built by the workers. "If they think they can build ships, let them go ahead and build them." As for the threat to build ships only in the East, "Well," said McKillop, "let them try it. If they want to start a revolution, let 'em start it."

To bring pressure on the strikers, the Retail Grocers Association decreed that no credit would be extended. The Cooperative Food Products Association, a cooperative formed by unions and the Grange, answered that food would be available to any striker. Thereupon the "dry squad" raided the co-op on a liquor warrant. This was an excuse to go through the co-op's correspondence and business files, which were confiscated in an effort to put it out of business.

The stalemate was complete. The men were adamant; many of the yard bosses had gone to California for a vacation; the government, far from being eager for a settlement, was bombarding the yards with messages to stand firm and resist labor's demands.

The idea of a general strike swept the ranks of organized labor like a gale. If labor was prepared to strike for Tom Mooney, certainly it could strike in support of the shipyard workers. If the general strike was labor's ultimate weapon, certainly here and now was the time to use it, to break the impending coastwise assault on unionism. Possibly there had never been a more dramatic meeting of the Central Labor Council than that which convened January 22, the floor jammed with delegates from some 110 local unions, and the gallery filled with unionists.

Every reference to the general strike was cheered to the echo; the cautions of the conservatives that such a strike was in violation of many international union rules and of contracts with employers were hooted down. It has been urged since that the absence of some 40 delegates returning from the Mooney convention gave the "radicals" dominance in the Council's deliberations. But most of the Mooney delegates were from the very same shipyard unions that were calling for a general strike; if they were willing to go to Chicago to plan a national strike for Mooney, they would hardly have been reluctant to counsel a general strike in Seattle in support of their own fellow workers.

If anything, the conservative influence was stronger in the Council that night than usual because the delegates who went to Chicago represented the moderate and radical unions. The conservatives weren't so concerned about Mooney as to travel 2,000 miles to agitate a general strike for him.

The Council's vote that night to hold a referendum among all local unions on the issue of a general strike won the approval of all delegates but one. Scholars, writing a generation later, refer to the "mysterious snowball" of assent that was registered on the very next night in eight local union meetings, whose galleries if any were certainly not "packed" by Wobblies; "the unanimity of sentiment and the rapidity of assent were astonishing." Perhaps now it seems astonishing, but in post-Armistice Seattle it was natural and inevitable--this great emotional wave.

By the weekend, it was so obvious that the strike votes would carry in most of the locals that a special meeting was called for Monday, January 26. There it was agreed that if the votes continued overwhelmingly in favor, another special meeting of union representatives should be called for Sunday, February 2, to decide on action. The strike votes in the metal trades unions of course were favorable; most of their members were already on strike. The crucial votes were in the old-established locals of the building, teaming, printing, and service trades. But the painters and carpenters and teamsters and cooks also voted "Yes."

In this they had the unanimous if left-handed support of the business press, which was busy taunting the "radical" leaders of the Central Labor Council that the rank and file, being patriotic Americans, would not strike against the government. Editorialized the Times: "A general strike directed at WHAT? The Government of the United States? Bosh! Not 15 percent of Seattle laborites would consider such a proposition." But consider it they did, and with the greatest enthusiasm! Edwin Selvin's Business Chronicle, spokesman for the open-shop interests which included most of industry and commerce, helped too. Selvin began inserting lurid advertisements in the business dailies proposing that all radicals be arrested and deported or jailed, that "the most labor-tyrannized city in America" be converted pronto into a bastion of the open shop. "Here is Seattle's solution to its labor problem: As fast as men strike, replace them with returned soldiers." Even conservative unionists who doubted the wisdom of the general strike recoiled when confronted by such evidence from the implacable class enemy.

On February 2, the special meeting of union representatives, three from each union, voted to set the strike date for Thursday, February 6. This group constituted itself the General Strike Committee and took over from the Central Labor Council complete authority for the strike. This relieved the Council of direct responsibility for an action which was thoroughly disapproved of by its chartering body, the A.F. of L., and which could result possibly in the revocation of its charter. Already the international unions were sending in their officials to hold back local unions which had voted to strike. An executive committee of 15 was chosen by the general committee to plan the details of the strike.

On the same day, an industrial relations committee of businessmen, clergy, and unionists negotiating with the shipyard owners got a promise to raise laborers to $5 a day minimum, but with no raise for the skilled trades. The Metal Trades Council spokesmen indicated that the offer could be discussed; but Piez was adamant. Not a ton of steel would be furnished the shipyards if the Macy award were altered.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY the relevancy of Lenin's speech on management, which had aroused so much discussion among workers, became apparent. If the strike were to be completely effective, the life of a city of 300,000 would grind to a sudden halt, with catastrophic consequences. If essential services such as light and power, fire protection, hospitals, were to continue, it was up to the Committee of 15 to cope with the problem of civic "management." Thousands of single workers ate in restaurants; were they to starve during the strike? How about milk for babies? And how was the strike to be policed? Certainly the unionists had little faith in the impartiality of the custodians of law and order.

An even more crucial question came up at the Committee of 15 meeting on Tuesday, February 4. How long would the strike last? Was this a demonstration of sympathetic support for the shipyard unions, to be ended as soon as labor had shown where its heart was? Or should it continue until the shipyard owners and the government agreed to confer? The leaders of the Central Labor Council, including Secretary Duncan, Editor Ault, Robert B. Hesketh (a city councilman), and others urged that a time limit be fixed--whether of one day or one week was less important than fixing some terminal date. But such was the wave of emotion that the proposal was defeated; the General Strike Committee was not yet ready to talk about ending a strike that had not even begun.

As a matter of cold fact, just what were the aims of the strike? Most unionists saw it as a demonstration of sympathy, calculated to strengthen the arm of the shipyard unions. Others felt that the first general strike in America would be so conclusive in its show of strength that the walls of Jericho would come tumbling down--not the walls of capitalism, but the walls of pitiless hostility to the earnest demands of the shipyard workers. For the proposed strike slogan, "We have nothing to lose but our chains and a world to gain," the Committee substituted, "Together we win."

As if to answer the question about aims of the strike, the Union Record on Tuesday, February 4, published the most famous editorial of its entire history--excerpts of which were read by millions across the country, who by now had their eyes riveted on what some were already proclaiming to be a revolutionary situation. The editorial, written by Anna Louise Strong and approved by Editor Ault and the Metal Trades Council, read, in part:

ON THURSDAY AT 10 A.M.

There will be many cheering, and there will be some who fear.

Both these emotions are useful, but not too much of either.

We are undertaking the most tremendous move ever made by LABOR in this country, a move which will lead--NO ONE KNOWS WHERE.

We do not need hysteria.

We need the iron march of labor.

LABOR WILL FEED THE PEOPLE.

Twelve great kitchens have been offered, and from them food will be distributed by the provision trades at low cost to all.

LABOR WILL CARE FOR THE BABIES AND THE SICK.

The milk-wagon drivers and the laundry drivers are arranging plans for supplying milk to babies, invalids and hospitals, and taking care of the cleaning of linen for hospitals.

LABOR WILL PRESERVE ORDER.

The strike committee is arranging for guards, and it is expected that the stopping of the cars will keep people at home.

A few hot-headed enthusiasts have complained that strikers only should be fed, and the general public left to endure severe discomfort. Aside from the inhumanitarian character of such suggestions, let them get this straight--

NOT THE WITHDRAWAL OF LABOR POWER, BUT THE POWER OF THE STRIKERS TO MANAGE WILL WIN THIS STRIKE...

The closing down of Seattle's industries, as a MERE SHUTDOWN, will not affect these eastern gentlemen much. They could let the whole northwest go to pieces, as far as money alone is concerned.

BUT, the closing down of the capitalistically controlled industries of Seattle, while the WORKERS ORGANIZE to feed the people, to care for the babies and the sick, to preserve order--THIS will move them, for this looks too much like the taking over of POWER by the workers.

Labor will not only SHUT DOWN the industries, but Labor will REOPEN, under the management of the appropriate trades, such activities as are needed to preserve public health and public peace. If the strike continues, Labor may feel led to avoid public suffering by reopening more and more activities,

UNDER ITS OWN MANAGEMENT.

And that is why we say that we are starting on a road that leads NO ONE KNOWS WHERE.

It could be said that the editorial contained no clear-cut answers to the questions about the purpose of the strike. Or rather it might be more correct to say that people could draw their own answers, to please their own interpretation. To most unionists the editorial stated plainly what was intended: that the city would be shut down but that essential services for life and security would continue. But others could read in ominous ideas that the workers, having shut down the industries, would reopen them on their own terms. Most of all the phrase that "we are starting on a road that leads--NO ONE KNOWS WHERE," created an alarm that Seattle labor was leading down the road to revolution. But the sentence meant exactly what it said--this was the first use of the general strike weapon anywhere in America, and who could foretell the outcome?