I will remember everything I have seen

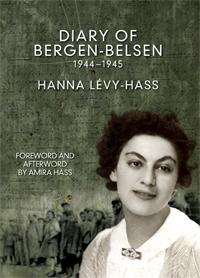

kept a journal while she was imprisoned at the Nazi interment camp Bergen-Belsen. Her writings have been collected in Diary of Bergen-Belsen, which provides a never-read-before view from a Jewish resistance fighter. Chronicling the last year inside the notorious concentration camp, Lévy-Hass tells her Holocaust survivor's story with clarity and attention to political and social divisions inside Bergen Belsen.

Amira Hass, Levy-Hass' daughter, who is renown today as the only Israeli journalist living and writing from the Occupied Territories, provides the introduction and afterword to this book, addressing the meaning of the Holocaust for Israelis and Palestinians today.

Here, we reprint several entries from Diary of Bergen-Belsen.

August 16, 1944

My whole being seems paralyzed and with each passing day I feel more apathetic about the world outside, less suited to life as it is now. If our goals and political aims don't materialize, if the world remains as it is now, if new social relations don't emerge and substantially change human nature--well, then, I will finally become and forever remain a clumsy, incompetent, damned creature, a failure.

Up to now I have frequently--even constantly--looked inside myself to find the causes of my misery and unhappiness--in my being, my character, my background. I've always struggled to understand the necessity behind human destiny, individual fate, and to explain such things in light of atavism, heredity, education, childhood, and any number of psychological factors. And I've done the same to understand and explain my own life. The method is sound, no doubt.

But recently it's becoming clearer to me that one's faults aren't something to look for solely in oneself or in one's personal life; they are largely hidden in the world around us. Today, I understand quite well that the endless string of bad days, the dark thoughts, and the extremely difficult situations I've lived through in my life were directly caused by none other than external vicissitudes, the absurdity of the current social structure, and human nature as it is today.

This becomes glaringly obvious today, right here, in this camp, and in the atrocious servitude that binds us to each other. And so I've learned to link my own particular destiny closely to the more general question that will determine the outcome to the current social and international upheaval, and I've learned to envision the solution to my own personal problems, above and beyond all else, within the context of the solution to global problems. So I've decided to stop being the victim of my previous convictions, to free myself from the clutches of individual fatalism that used to throw me defenselessly into an imminent, inevitable, predestined, eternal, and necessarily fatal unhappiness. It goes without saying that in spite of everything, my personal unhappiness flows from these kinds of things, in a sense; but that unhappiness is not a definitive and stable feature, since it must, since it can't not vary within the general context of the social and global transformations taking place today.

August 19, 1944

People from different social classes are crammed together here, but it's the standard petty-bourgeois type that predominates. There are also a few typical capitalist individuals, moderately decadent types. In general, everyone continues to display mean and petty habits, selfishness, and narrow-mindedness. Out of this come endless conflicts of interest, friction and cases of bigotry on top of it all.

The atmosphere is suffocating. The fact that we were all deported here from every corner of the world and that you hear no fewer than twenty-five languages being spoken is not the worst of it. If only we were united by one determined, common consciousness! But this is not the case. This human mass is heterogeneous. It is piled together here, by force, by violence, in this small patch of dirty, humid ground, forced to live in the most humiliating conditions and to endure the most brutal deprivations, such that all human passions and weaknesses have unleashed themselves, sometimes taking on beastly forms.

What a disgrace! What a sad spectacle! A common misery uniting beings who barely tolerate each other and who add their own lack of social consciousness, mental blindness, as well as those incurable ills of isolated souls, to these distressing objective conditions. Certain selfish instincts have found in this place an ideal ground for their own justification to the point of being grotesque. Nonetheless, it would be wrong to generalize all these problems. But the high moral values that you can sense in some people, their moral and intellectual honesty, remain in the shadows, powerless.

November 8, 1944

I would love to feel something pleasant, aesthetic, to awaken nobler, tender feelings, dignified emotions. It's hard. I press my imagination, but nothing comes. Our existence has something cruel, beastly about it. Everything human is reduced to zero. Bonds of friendship remain in place only by force of habit, but intolerance is generally the victor. Memories of beauty are erased; the artistic joys of the past are inconceivable in our current state. The brain is as if paralyzed, the spirit violated.

The moral bruises run so deep that our entire being seems atrophied by them. We have the impression that we're separated from the normal world of the past by a massive, thick wall. Our emotional capacity seems blunt, faded. We no longer even remember our own past. No matter how hard I strive to reconstruct the slightest element of my past life, not a single human memory comes back to me.

We have not died, but we are dead. They've managed to kill in us not only our right to life in the present and for many of us, to be sure, the right to a future life...but what is most tragic is that they have succeeded, with their sadistic and depraved methods, in killing in us all sense of a human life in our past, all feeling of normal human beings endowed with a normal past, up to even the very consciousness of having existed at one time as human beings worthy of this name.

I turn things over in my mind, I want to...and I remember absolutely nothing. It's as though it wasn't me. Everything is expunged from my mind. During the first few weeks, we were still somewhat connected to our past lives internally; we still had a taste for dreams, for memories. But the humiliating and degrading life of the camp has so brutally sliced apart our cohesion that any moral effort to distance ourselves in the slightest from the dark reality around us ends up being grotesque--a useless torment. Our soul is as though caught in a crust that nothing can soften or break.

And to think that this is only our fifth month here and that we are in a camp that, if you believe the Germans, is not among the worst...And yet, what a deadly night!

I will definitely remember everything I have seen, experienced and learned, everything that human nature has revealed to me. From this moment on it is encrusted in the depths of my soul. And in normal life (but what is in essence normal? All this, this eternalized anguish--or rather what is beyond, before and after?) I will never again be able to forget, I believe, the findings and verdicts arrived at here: I will measure each man against the criteria of today's reality, from the perspective of what he was or could have been in these conditions of ours. To form an opinion of someone, to have a high opinion of him or not, to like him or not, everything will depend first and foremost on knowing what his behavior, his physical, moral and psychological reaction was or might have been during these dark years characterized by great trials--the force of his character, his emotional endurance. I will no longer be able to separate my thoughts from my understanding of war's events; the two will be intimately linked forever in my mind.