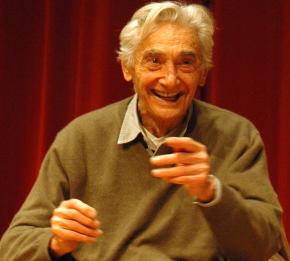

The people’s historian

pays tribute to a historian who helped make history.

HOWARD ZINN, an activist and author for half a century and probably the best-known voice of the U.S. left, died January 27 at the age of 87.

Howard was a fixture of countless struggles for justice and equality in the U.S. over many long decades. He was as determined in his 80s as he was many years before as a witness and participant in the great battles of the civil rights movement and the fight against the Vietnam War.

He died of a heart attack in Santa Monica, Calif., where he was enjoying a few days' vacation. But according to friends, he was also looking forward to his next speaking event in a week's time--to a packed audience, as always.

Howard is best remembered for A People's History of the United States, which taught millions about the hidden tradition of protest, resistance and rebellion in America. A People's History has sold over 2 million copies--it's almost unique in the publishing world for continuously selling more copies each year than it did the year before.

In 2004, Howard and coauthor Anthony Arnove produced a companion volume--Voices of a People's History of the United States, which compiled speeches, articles and essays, poetry and song lyrics from those who were a part of the struggles chronicled in A People's History. Voices brought the words of Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Eugene V. Debs, Fannie Lou Hamer and many, many more to a new generation.

In December, Voices was brought to film in a magnificent two-hour program seen by millions of people on The History Channel. Selections from the book were performed by a remarkable cast of actors like Morgan Freeman, Matt Damon and Marisa Tomei; musical artists like John Legend and Bruce Springsteen; and poets like Staceyann Chin.

Besides A People's History and Voices, there were so many other books. SNCC: The New Abolitionists reported from the front lines of the civil rights struggle in the early 1960s. A range of writings over decades, from Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal to Terrorism and War, challenged militarism and imperialism.

Zinn also showed off his talents as a playwright--among his plays were Emma, about anarchist Emma Goldman, and Marx in Soho, which brought Karl Marx back to life in modern-day Soho in New York City to reflect on the relevance of socialist ideas today.

"His writings," Noam Chomsky wrote in a passage quoted by the Boston Globe, "have changed the consciousness of a generation, and helped open new paths to understanding and its crucial meaning for our lives."

BUT CHOMSKY rightly went on to add: "When action has been called for, one could always be confident that he would be on the front lines, an example and trustworthy guide."

If Howard gained his greatest renown as a historian, his own life displayed the same courage and commitment as the struggles that he chronicled--he lived his life as a part of the fight for a better world.

Howard was born in 1922 in New York City, the son of working-class Jewish immigrants. After attending school, he went to work in the Brooklyn Navy Yards, where he was an agitator on the shop floor from the start.

He joined the Army Air Force during the Second World War and served as a bombardier--a mission in 1945 involved one of the first uses of napalm. The experience informed his opposition to war in the years after--as he often pointed out in speeches, the stated claim that the "good war" was about defeating fascism was in conflict with the U.S. government's ruthless pursuit of political and business interests.

After the war, Howard was able to attend New York University on the GI Bill, studying history. In 1956, he was hired to be a professor at Atlanta's Spelman College, a historically Black women's college.

The civil rights movement was brewing as he and his wife Rosyln arrived in the South. Howard was a witness to its battles, serving as an adviser to young student activists, some of whom went on to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. But he was also a participant in sit-ins and marches.

After being fired for championing the protests of Spelman students against the conservative college administration, Howard came north to teach at Boston University.

There, he was part of the early movement against the Vietnam War. In 1968, as liberation fighters launched the Tet Offensive, Howard visited the North Vietnamese capital of Hanoi with another leading activist, Rev. Daniel Berrigan. In the U.S., Howard helped publicize the Pentagon Papers--a damning indictment of U.S. war plans leaked by military insider Daniel Ellsberg. His lean frame was a familiar sight on the speakers' platform at antiwar protests on Boston Common and around the country.

Howard's commitment to protest continued throughout his life, whether the cause was opposing U.S. wars in the Middle East, challenging the criminal injustice system, defending the rights of union workers, or speaking up for the victims of government repression. He was selfless with his time, answering countless invitations from many different movements and struggles.

At the heart of it was Howard's understanding that it was possible to achieve justice, but only if ordinary people fought for it. As he put it in a speech a year ago that was published at SocialistWorker.org:

We are citizens. We must not put ourselves in the position of looking at the world from [the politicians'] eyes and say, "Well, we have to compromise, we have to do this for political reasons." We have to speak our minds.

This is the position that the abolitionists were in before the Civil War, and people said, "Well, you have to look at it from Lincoln's point of view." Lincoln didn't believe that his first priority was abolishing slavery. But the anti-slavery movement did, and the abolitionists said, "We're not going to put ourselves in Lincoln's position. We are going to express our own position, and we are going to express it so powerfully that Lincoln will have to listen to us."

And the anti-slavery movement grew large enough and powerful enough that Lincoln had to listen. That's how we got the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th and 14th and 15th Amendments.

That's been the story of this country. Where progress has been made, wherever any kind of injustice has been overturned, it's been because people acted as citizens, and not as politicians. They didn't just moan. They worked, they acted, they organized, they rioted if necessary.

IN A country with a long record of violently suppressing resistance and then erasing it from the history books, the importance of what Howard contributed can't be overstated. As Nation columnist and SocialistWorker.org contributor Dave Zirin wrote in tribute to Howard:

With his death, we lose a man who did nothing less than rewrite the narrative of the United States. We lose a historian who also made history.

Anyone who believes that the United States is immune to radical politics never attended a lecture by Howard Zinn. The rooms would be packed to the rafters, as entire families, black, white and brown, would arrive to hear their own history made humorous as well as heroic. "What matters is not who's sitting in the White House. What matters is who's sitting in!" he would say with a mischievous grin. After this casual suggestion of civil disobedience, the crowd would burst into laughter and applause. Only Howard could pull that off because he was entirely authentic.

Howard was an inspiration to all of us on the left, especially in the times when we were fighting difficult battles and not winning many. His writings taught us that the resistance to oppression lives on--and that the struggles of ordinary people have the potential to change the world.

They also taught us something else: that every high point of struggle is only possible because of the smaller battles that came before it--ultimately, that it matters what individuals do now to oppose injustice and to organize for the future.

The words that end Howard's autobiography, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train, are the best tribute to his extraordinary life:

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness.

What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places--and there are so many--where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of the world in a different direction.

And if we do act, in however small a way, we don't have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory.