School reform fails in test score scandal

, a former public school teacher in New York, looks at the issues raised by the big downward revision of student test scores in the city.

A SCANDAL over miscalculated test scores in New York City has highlighted everything that's wrong with the national obsession over equating teacher effectiveness with test scores.

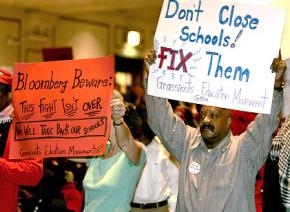

The issue heated up when an outraged group of parents shut down the city's Panel for Education Policy (PEP) meeting August 30 over a dramatic drop in the student scores on state tests after the results were recalculated.

After a presentation by the PEP on the downward revisions to the test scores, panel member Patrick Sullivan made a motion to let the 100-plus parents and the supporters at the meeting to speak on what he called "one of the worst debacles in the history of the public school system."

Though another panel member seconded the motion, the PEP chairperson refused to let the public participate immediately and decreed that they would have to wait until the end of the meeting to speak. At that point, the furious crowd erupted with jeers and began chanting, "Let us speak!" The crowd kept up the pressure, drowning out the speakers on the stage and eventually forcing the meeting to adjourn.

After members of the PEP left the stage, parents held their own meeting at the front of the auditorium, where they testified about the false promises, misinformation and lack of accountability of Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Schools Chancellor Joel Klein. The meeting ended when the parents marched out, chanting, "We'll be back!"

The parents' protest, organized in part by the Coalition for Educational Justice (CEJ), comes in response to New York State's recently released standardized test scores, which showed a precipitous drop in achievement in city schools. Bloomberg and Klein have trumpeted the revival of public education in New York City primarily through the supposedly meteoric rise in test scores during their stewardship of the school system.

Those state test scores are the basis of report card evaluations that Bloomberg and Klein use to rate public schools. But earlier this year, the New York State Education Department, responsible for administering the tests, admitted that the tests had become easier over time, promising to change the grading method to "raise standards."

What that meant, however, was a total reversal of fortune for schools and students, who had previously perceived they were making progress on the exams. Citywide, the proficiency rate in math fell from 82 percent last year to 54 percent this year. In English, the drop was from 69 percent to 42 percent.

As the New York Times reported, in some schools, the reversal of fortune was even more dramatic. At Public School 85 in the Bronx, third-grade math proficiency went from 81 percent last year to 18 percent this year. At Harlem Promise Academy, a charter school, third grade math proficiency dropped from 100 percent to 56 percent.

THE PEP's attempt to spin these numbers as business as usual was challenged by the noisy CEJ action. In the mainstream press, the parents were heavily criticized for the "disruption" they caused. For example, the Times wrote in an August 18 editorial headlined "Parents need to know":

Parents in New York City are understandably worried about the performance of students on this year's state math and reading tests. But an angry, jeering community group, equipped with a bullhorn, did children no favors when it disrupted a meeting this week where city education officials tried to calm fears about the new approach to testing.

But this blame-the-parents perspective obscures the real nature of the debate. First, the parents' bullhorn can't even be compared to the administration's access to media outlets like the New York Post, which faithfully publishes pro-Bloomberg editorials and frequently provides space for Klein himself to publish articles.

Furthermore, while ostensibly established to provide a democratic balance to Bloomberg's control of New York City schools, the PEP has historically operated more like a rubber stamp than a counterweight to the mayor's policies.

In fact, PEP is made up of a permanent majority of mayoral appointees. The first mayoral appointees to the panel made the mistake of voting against one of Bloomberg's proposals and were promptly removed from their positions.

In January 2010, after 2,000 parents, students and teachers showed up to protest the closing of 19 public schools and gave nine hours of testimony as to why the schools shouldn't be closed, Bloomberg's appointees to the panel voted unanimously to continue with the closings in accordance with the mayor's policies.

As Diane Ravitch, a former official in the federal Department of Education--appointed by George H.W. Bush, no less--turned critic of school reform, points out in her scathing Washington Post blog post on mayoral control of schools:

When Mayor Bloomberg first ran for office, he said that the legislature should give him control of the school system with minimal checks or balances. He promised accountability. If anything went wrong, the public would know whom to hold accountable; not some faceless board, but he, the mayor, would be accountable.

Cities that have implemented mayoral control of schools cannot show progress significantly better than cities without mayoral control. Further, as communities in cities with mayoral control have found out, they no longer have a say in what goes on in their neighborhood school. What mayoral control has meant in practice is less parent involvement, less accountability, more union busting, more privatization and more "blame-the-teacher" rhetoric than you could fill a textbook with.

Ravitch also pointed out that "the achievement gap among students of different racial and ethnic groups grew larger, as large as it was when the mayor took office."

Indeed, in an independent study of the New York City DOE's figures, the Coalition for Educational Justice found that 76 percent of students in the top 10 percent of schools by income passed the eighth grade math exam, while only 33 percent in the bottom 10 percent of schools by income passed the exam.

To take a specific example, scores at PS 192, in the better-off neighborhood of Borough Park in Brooklyn, remained essentially unchanged. There, proficiency in third grade math went to 99 percent from 100 percent last year, and the fourth-grade English proficiency rating went to 96 percent from 99 percent last year.

The controversy forced Schools Chancellor Klein to use the New York Post to publish an op-ed article claiming:

On both state and national tests, as well as with respect to high-school graduation and college attendance, the Bloomberg administration has made undeniable progress in closing these gaps in our public schools. Our entire student body has made major gains, but African-American and Hispanic students in particular have outpaced the progress of their white peers in the city and nationwide.

Leonie Haimson, executive director of the advocacy group Class Size Matters, deconstructed Klein's editorial in an e-mail message to the NYC Education News listserve:

Though Klein tries to slip in a novel comparison here--the gap between NYC Black and Hispanic students and white students nationwide--this is not the definition used in any other analysis. He also uses the 2002 instead of the 2003 date, when his reforms began. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, there has been no significant closing of the achievement gap among NYC students, in any grade or any subject, either white-black or white-Hispanic since 2003, when the Klein reforms began; even if you use his comparisons, the figures aren't correct.

THE NEW York test scores scandal is a powerful example of everything wrong with the education "reform" agenda being pushed by the Obama White House through its "Race to the Top" education program.

"Race to the Top" forces states to compete for education funding by awarding them points for creating plans to satisfy the bill's reforms. For example, states can get up to 138 points in the sub-section titled, "Great Teachers and Leaders"--the largest percentage of those points (58 points) coming from "improving teacher and principal effectiveness based on performance."

"Effectiveness based on performance" has largely been interpreted by the states to mean linking teacher evaluations to their student's performance on standardized tests, a method of evaluation known as the "value-added model." In this approach, a student's average gain on standardized tests in considered the norm, and a teacher is rated by comparing the amount of progress the student made relative to their average gain.

The value-added model has gotten a lift most recently from Michele Rhee, chancellor of the Washington, D.C., public schools, when she fired teachers this year whose "value-added" scores were purportedly too low. More recently, the Los Angeles Times recently published its own calculation of value-added scores of LA public school teachers using data from students' state test scores.

Ideologically, the "value-added" model rests on the assumption that the most important factor in determining student achievement is the effectiveness of their teacher. Therefore, the best way to improve achievement in public schools is to create incentives for "effective" teachers and fire the ineffective ones.

The test score scandal in New York City, however, highlights how absurd and arbitrary it is to use such tests to evaluate teachers. Despite the attempt of "experts" to scapegoat teachers as the problem with our education system, the best predictor of student achievement on tests is, and always has been, social class--not the performance of individual teachers.

None of the proposed reforms adequately address the issues that most dramatically effect poor students' performance in school: homelessness, hunger and lack of access to health care.

As a former public school teacher, I knew a bill for universal health care would have had an infinitely more direct and positive effect on my inner-city students' performance than any fiddling with standardized tests could. The same goes for food stamps, which the government recently cut by billions, and homelessness, long a challenge faced by urban teachers and now exacerbated by the ongoing crisis in jobs and mortgages.

It's clear who should be held accountable for an education system that has consistently and historically failed to provide an adequate education to poor students here in New York and across the nation: the administrators of that system, not the workers. It is teachers who dedicate their lives to working in chronically challenging conditions with the neediest students.

Only a movement of teachers, parents and students will be strong enough to wrest control of our schools from the hands of the people responsible for their mismanagement and put forward our own version of education reform--democratic control of our schools.