The struggle that set the stage for a Civil War

The opening shots of the American Civil War were fired 150 years ago today--but as explains, the abolitionists' war on slavery began decades before.

APRIL 12 will be the 150th anniversary of the event generally seen as the start of the American Civil War--the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, a U.S. government fort guarding the entrance to Charleston Harbor in South Carolina.

In fact, Fort Sumter had been besieged for months by the South Carolina state government, backed up by the newly forming Confederate Army, and was within days of running out of food and other supplies.

South Carolina had been the first Southern state to secede from the U.S. following the victory of anti-slavery Republican Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election. It was followed into the Confederacy within weeks by six more states: Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. After Sumter was bombed and Lincoln called for the mobilization of 75,000 soldiers to restore federal power in the South, four more states seceded: Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina.

Lincoln had attempted to placate the Southern states even after the secessions began. In his Inaugural Address, he proposed a constitutional amendment to guarantee that slavery would remain legal in the states where it existed at the time--it would have been the 13th Amendment, the one that today bans slavery.

Thus, as the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, the Civil War began at Fort Sumter with both sides fighting "in the interest of slavery...The South was fighting to take slavery out of the Union, and the North was fighting to keep it in the Union."

But Douglass foresaw--as did a German socialist living in England at the time by the name of Karl Marx--that the war would have to confront slavery head-on. As Douglass wrote in his newspaper The North Star, "The American people and the government at Washington may refuse to recognize it for a time, but the inexorable logic of events will force it upon them in the end--that the war now being waged in this land is a war for and against slavery."

Thus, the coming of the Civil War was celebrated by opponents of slavery, North and South--by the Black slaves still subject to the rule of the plantation owners; by free Blacks like Douglass who were the heart of the movement against slavery; and by the hundreds of thousands of white Northerners devoted to the cause of abolition.

There will be many more articles to come about Civil War anniversaries, on this website and others, as the 150-year milestones are ticked off. This one is an introduction to the struggle that came before the war, reaching back over decades--the struggle of the abolitionists.

THE UNITED States was formed with a contradiction at its heart.

The American Revolution was fought to end the rule of Britain's monarchy in its North American colonies, and the rebellion's Declaration of Independence was an expression of the era's highest democratic ideals, such as "all men are created equal."

But of course, all men weren't equal in America--at the time of the revolution, there were more than 1 million African slaves in the colonies.

The horrors of slavery are impossible to overstate--from the kidnapping of Africans and the barbaric "Middle Passage" across the Atlantic, to the sale of human beings on the auction block in Southern cities like Charleston. As Frederick Douglass recounted in his autobiography:

We worked all weathers. It was never too hot or too cold; it could never rain, blow, snow or hail too hard for us to work in the field...I had neither sufficient time in which to eat, or to sleep, except on Sundays. The overwork and the brutal chastisements of which I was the victim, combined with the ever-gnawing and soul-devouring thought--"I am a slave, and a slave for life, a slave with no rational ground to hope for freedom"--rendered me a living embodiment of mental and physical wretchedness.

Among at least a minority of whites, there was moral opposition to this monstrous injustice from before the 1776 revolution, and it was at first as likely to be found in Southern states, where slavery was largely confined by the time of independence, as Northern ones.

But this changed with the growing economic importance of cotton--a crop suited to the plantation agriculture system of the South, which would become the crucial raw material for the textile mills of England as the Industrial Revolution was taking off. Exports of cotton grew from almost nothing at all in 1790 to a majority of U.S. overseas trade in 20 years.

Cotton became the cornerstone of great business empires in Europe and the financial fortunes of the Southern plantation owners--and slave labor was at the heart of it all. By 1820, there were 1.5 million slaves out of a U.S. population of 9.5 million. So around one in every six people in the "land of the free" was owned.

With so much money to be made, even moral opposition to slavery could no longer be tolerated in the Southern states--abolitionism was driven out, both ideologically and physically.

The divide between North and South hardened as the two economic systems--one based on slave labor in the South, and the other on small farming and wage labor in the factories of the North--pulled in different direction. The "irrepressible conflict" between North and South, as abolitionist William Seward called it, spawned political battles on questions ranging from tariffs and free trade to foreign policy.

The U.S. political system had always reflected this tension. As the late socialist and historian Peter Camejo put it, the wealthy plantation owners and merchants who wrote the Constitution had two chief concerns--to insulate their power from the mass of small farmers and propertyless urban dwellers on the one hand, and to navigate the questions that divided them.

Thus, the Constitution, with its elaborate "checks and balances," both "kept popular rule to a minimum and gave the two wings of the ruling class a system for working together while protecting their separate interests," Camejo wrote. As a result, the North-South conflict was papered over by a series of compromises, many of them revolving around the status of slavery in the new states admitted into the U.S.

Thanks to the Constitution's "three-fifths" rule--that slaves would be counted as three-fifths of a person when it came to allocating political representation, but allowed no rights--the South dominated the federal government before the Civil War. As the new industrial system developed and spread in the North--thanks to the growing reach of the railroads and an influx of immigration from Europe to provide labor for the factories, among other factors--the Northern capitalists chafed under the South's dominance.

But economic interests alone wouldn't have brought the "irrepressible conflict" to the breaking point. Even as Northern industry developed, the U.S. economy as a whole remained shaped by cotton production before the Civil War--the same Northern merchants who invested in the new factories helped finance and export Southern cotton, Midwestern farmers who resented the power of the plantation owners raised food that was sent south to feed the slaves.

A political struggle was also necessary before the Northern system would assert itself against the South. And the vanguard of that struggle were those who were determined to oppose not just the political power of the slave owners, but the vile institution of slavery itself--and to see it abolished at any cost.

IN 1820, John Quincy Adams--the son of 1776 revolutionary John Adams, an outspoken opponent of slavery, and at that point U.S. Secretary of State--foresaw the Civil War to come 40 years later in this entry in his diary:

If slavery be the destined sword in the hand of the destroying angel which is to sever the ties of this Union, the same sword will cut in sunder the bonds of slavery itself. A dissolution of the Union for the cause of slavery would be followed by a servile war in the slave-holding States, combined with a war between the two severed portions of the Union. It seems to me that its result must be the extirpation of slavery from this whole continent; and calamitous and desolating as this course of events in its progress must be, so glorious would be its final issue that, as God shall judge me, I dare not say that it is not to be desired.

This revolutionary attitude is all the more amazing considering that Adams would occupy the White House in a few years' time! But among abolitionists, such a view was still the exception. Most opposition to slavery remained a matter of moral sentiment, not of action--and the consensus was still that slavery would eventually fade out of existence.

The most important factor in transforming abolitionism was the action and agitation of Blacks themselves.

On the Southern plantations, slaves showed their determination to be free. Resistance on a small and informal scale--such as avoiding work in the fields or breaking tools--was continuous. Organized slave rebellions, like the one led by Nat Turner in 1831, struck fear into the hearts of the slave owners, and were only put down through the utmost violence.

The Underground Railroad helped slaves escape to the North--by one estimate, 100,000 fled bondage this way by 1850. Most of the "conductors" on the Railroad were Black, especially in the decades approaching the Civil War, and the passengers who gained their freedom provided the most powerful testimony to the horrors of the slave system. Former slaves like Douglass became enthusiastic organizers and agitators. As historian Herbert Aptheker wrote:

Without the initiative of the Afro-American people, without their illumination of the nature of slavery, without their persistent struggle to be free, there would have been no national Abolitionist movement. And when the movement did appear, the participation of Black people in every aspect was indispensable to its functioning and its eventual success.

William Lloyd Garrison, a white Massachusetts printer and journalist who would devote his life to the struggle against slavery, is often credited with being the "father of abolitionism." But Garrison had to be educated about the question--he at first accepted the idea that the answer to slavery was for free Blacks to emigrate to a territory on the West coast of Africa. He later credited his Black friends with convincing him about abolition.

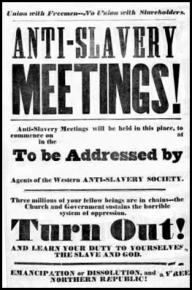

GARRISON'S CONVERSION had an important effect on the abolitionist movement. He founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society--and in 1831, he launched a weekly anti-slavery newspaper called The Liberator that would prove to be a lightning rod for abolitionists, Black and white, who were breaking from the conception that emancipation had to come gradually. As Garrison wrote in an editorial in the paper's first edition:

On this subject, I do not wish to think, or to speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen; but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest--I will not equivocate--I will not excuse--I will not retreat a single inch--AND I WILL BE HEARD.

This absolute refusal to compromise is important to keep in mind in understanding the philosophy of Garrison and his followers--which included every prominent radical abolitionist, including Douglass, for at least some period of time.

The Garrisonians rejected any involvement in politics. They believed that slavery must be overthrown by building overwhelming moral pressure against the slave owners, that the movement would have to be nonviolent in contrast to the violence of slavery, and that Northern states would be better off seceding from the U.S. than maintaining any association with the South.

Such ideas might seem strange today, but they represented a hard-won advance for the abolitionist movement against the dominant belief that emancipation would come gradually and inevitably, through existing institutions. The Garrisonian hostility to political involvement was really a response to the corruption of a U.S. political system that produced endless compromises with the Southern slaveocracy--a system in which the Constitution itself was "infected with the pestilence of slavery."

Against this backdrop, The Liberator was a badly needed call to action for all those who yearned to do more than wait for slavery to fade away. As Douglass later recalled:

The paper became my meat and my drink. My soul was set all on fire. Its sympathy for my brethren in bonds--its scathing denunciations of slaveholders--its faithful exposures of slavery--and its powerful attacks upon the upholders of the institution--sent a thrill of joy through my soul, such as I had never felt before!

Above all, these new abolitionists were devoted to the cause, no matter what the sacrifice. Another leading voice of the movement, Wendell Phillips, recalled that he first laid eyes on Garrison in 1835 when the Liberator editor was being dragged through the streets of Boston by a mob of anti-abolitionists who wanted to see him lynched. John Brown, who would lead a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in Virginia in the hopes of sparking a slave insurrection, decided he had to act on his anti-slavery beliefs when he learned about Rev. Elijah Lovejoy, who was murdered in downstate Illinois by pro-slavery vigilantes while defending his abolitionist printing press.

Under the influence of leaders like Garrison, Douglass and Phillips, a more vibrant abolitionist movement began to develop practices that will seem familiar to socialists and activists today.

In the late 1830s, abolitionists spread out through the North to collect 1 million signatures on a petition to repeal the gag rule that barred Congress from discussing anti-slavery resolutions. Newspapers like The Liberator were eagerly distributed, and scores of pamphlets sold in the hundreds of thousands.

In cities and towns, people would pack into lecture halls to hear abolitionist agitators. According to the editor of Frederick Douglass' speeches and writings, a "partial" list of speaking events for Douglass in January 1855 included at least 21 addresses, in cities from Maine and Massachusetts to New York and Pennsylvania. All told, between 1855 and 1863, Douglass gave more than 500 known speeches in the U.S., Britain and Canada.

Herbert Aptheker's Abolitionism describes a "school" organized to train activists in November 1836:

Theodore Weld had recruited about 50 people prepared to devote themselves to spreading the movement's message. Most of them attended what might well be called, in modern terms, a cadre-training school in New York City. From November 15 through December 2, these volunteer students heard the questions most commonly asked of abolitionists; suggesting appropriate answers were experts Theodore Weld, the Grimké sisters--Angelina and Sarah--William Lloyd Garrison, James G. Birney and others.

THROUGH SUCH efforts, abolitionism became a mass movement. As early as November 1837, Garrison estimated that the number of local anti-slavery societies was "not less than 1,200"--with a total membership of 100,000 people.

Meanwhile, events themselves were driving abolitionists to more and more radical conclusions.

In the mid-1840s, pro-slavery President James Polk launched a war on Mexico with the clear aim of seizing new territories in the West that could then be brought into the U.S. as slave states. In 1850, another compromise about Western expansion was brokered in Congress--but one provision was the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, which put the power of the federal government behind the South's "slave-catchers."

Even moderate opponents of slavery were infuriated. "This filthy enactment was made in the 19th century by people who could read and write," wrote the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. "I will not obey it, by God."

The Garrisonian orthodoxies--about nonviolence, for example--made less and less sense when agents of the plantation owners had basically been empowered to kidnap Blacks.

In 1854, for example, Anthony Burns, a former slave living in Boston, was ordered to be returned to slavery. A mass attempt to free him from the jail where he was being held barely failed. The next day, Burns had to be guarded by hundreds of police and soldiers as he was brought to the harbor to be put on board a ship bound for the South. As one resident recalled, "We went to bed one night old-fashioned conservative Compromise Union Whigs, and waked up stark mad abolitionists."

Douglass had already broken with Garrison and launched his own newspaper, The North Star, but the Fugitive Slave Act reinforced that direction. "The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter," Douglass wrote, "is to make a half-dozen or more dead kidnappers."

Douglass' words reflected the growing support, even among previous advocates of nonviolence, for slave insurrection and direct action against the slave owners. In July 1856, Gerrit Smith, a wealthy philanthropist and veteran of the movement, spoke for many others when he said there might have been a time in the past "when slavery could have been ended by political action. But that time has gone by--and, as I apprehend, forever. There was not virtue enough in the American people to bring slavery to a bloodless termination; and all that remains for them is to bring it to a bloody one."

The radicalization of the abolitionists emerged on other social and political questions. As Aptheker points out, the movement against slavery helped propel the movement for women's rights. Abolitionism, he wrote "was the first great social movement in U.S. history in which women fully participated in every capacity: as organizers, propagandists, petitioners, lecturers, authors, editors, executives and especially rank-and-filers."

Many abolitionists were also determined to challenge racism among Northerners who opposed the Southern slave power, but also opposed equality and democratic rights for freed slaves. The Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1838 adopted a resolution proposed by Sarah Grimké that insisted:

It is the duty of Abolitionists to identify themselves with these oppressed Americans, by sitting with them in places of worship, by appearing with them in our streets, by giving them our countenances in steamboats and stages, by visiting them in their homes, and encouraging them to visit us, receiving them as we do our fellow citizens.

Beyond this, the leading figures of the movement saw themselves as connected to other struggles around the world--the revolutions for democracy in Europe, for example. Thus, John Brown--who has gone down in history as a violent fanatic after the Harpers Ferry raid--had a world view that extended beyond slavery, as one man who camped with Brown learned during a late-night political discussion:

One of the most interesting things in [Brown's] conversation that night, and one that marked him as a theorist, was his treatment of our forms of social and political life. He thought that society ought to be organized on a less selfish basis; for while material interests gained something by the deification of pure selfishness, men and women lost much by it. He said that all great reforms, like the Christian religion, were based on broad, generous, self-sacrificing principles. He condemned the sale of land as a chattel, and thought that there was in indefinite number of wrongs to right before society would be what it should be, but that in our country, slavery was the "sum of all villainies," and its abolition the first essential work.

By this point, abolitionism had become a revolutionary movement, as the 20th century Marxist and historian CLR James wrote. Its supporters were ready:

to tear up the roots and foundation of the Southern economy and society, wreck Northern commerce, and disrupt the Union irretrievably...They renounced all traditional politics...They openly hoped for the defeat of their own country in the Mexican War...They preached and practiced Negro equality. They endorsed and fought for the equality of women.

ANOTHER GARRISONIAN principle that radicals like Douglass came to question was non-involvement in politics. Douglass came to the conclusion that if the North mobilized its political power--if control of the White House and Congress was won by an anti-slavery party--the federal government could be transformed from a tool of compromise and cooperation with slavery into a weapon against it.

Douglass supported a series of third-party challenges to the dominant Democrats and Whigs--the Liberty Party, the Free Soil Party and finally the Republican Party, which formed in 1854 as the political battles between North and South reached a new level.

The Republicans were not an abolitionist party, though anti-slavery figures were prominent within it. But it also included other political forces, including anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic Nativists. The point of unity was opposition to the political power of the Southern slaveocracy. The different elements of the party at least agreed on opposition to the expansion of slavery into new territories--and potential new states--in the West.

For the 1860 presidential election, more prominent abolitionist voices were passed over for the presidential nomination in favor of Abraham Lincoln. Personally, Lincoln abhorred slavery, but he opposed taking action in the name of abolition--like challenging the Fugitive Slave Act, for example. He won the nomination because he was at the middle point between the factions of the Republican Party.

Douglass zeroed in on the contradictions of Lincoln and the Republicans:

The Republican Party...is opposed to the political power of slavery, rather than to slavery itself. It would arrest the spread of the slave system...and defeat all plans for giving slavery any further guarantee of permanence. This is very desirable, but it leaves the great work of abolishing slavery...still to be accomplished. The triumph of the Republican Party will only open the way for this great work.

Nevertheless, Douglass disagreed with calls from other abolitionists to boycott the 1860 election--because he recognized that a victory for Lincoln would "open the way for this great work." As he wrote a few months before the election:

I cannot fail to see that the Republican Party carries with it the anti-slavery sentiment of the North, and that a victory gained by it in the present canvass will be a victory gained by that sentiment over the wickedly aggressive pro-slavery sentiment of the country...The slaveholders know that the day of their power is over when a Republican president is elected.

Those words were prophetic. Lincoln's victory over a divided pro-slavery opposition spurred the Southern secessions that began within two months of the election. As timid as it may have seemed to the radical abolitionists, the Republicans' declaration that they would oppose the expansion of slavery would inevitably undermine the South's dominant position in the federal government--and that would be the beginning of the end for the slaveocracy.

The South chose to fight sooner than later, and the Civil War began. Because the North entered the war with a policy of merely keeping the Union together, the Confederacy was initially successful. But as Douglass foresaw, the war to "save the Union" eventually became a war to end slavery.

Again, the abolitionists--including Black abolitionists, and especially Black slaves--played the critical role in this transformation. For example, once Lincoln finally agreed to the formation of Black units, former slaves and free Blacks streamed into the Union Army. By the time the South surrendered in 1865, there were 166 Black regiments, comprising about one-eighth of Union soldiers. The Union Army had become an army of liberation.

The Civil War may have begun at Fort Sumter with both sides, in Douglass' words, fighting for slavery, but it ended four bloody years later as a war that destroyed slavery--thanks in no small measure to the long struggle of the abolitionists in the decades before.