When the cops are the rapists

and report on revelations about incidents of rape and sexual assault perpetrated by Chicago police--and what it will take to get justice.

RECENT INCIDENTS of alleged rape and sexual assault by Chicago police officers are causing outrage--and leaving many Chicagoans to ask how we can ever be safe if those with such power can get away with violating us.

In May, a 22-year-old woman (who remains anonymous) filed a federal lawsuit alleging that she was raped by two Chicago police officers on March 30.

According to the Chicago Tribune, "The suit alleged that the abuse was facilitated by a 'code of silence' among officers and an unwillingness by supervisors to investigate wrongdoing. 'Chicago police officers accused of sexual misconduct against citizens can be confident that the city will not investigate those accusations in earnest,' the lawsuit charged."

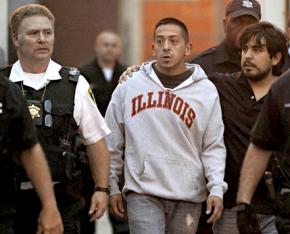

Although relieved of their duties on March 31 after the victim made her complaint, it wasn't until May 12 that officers Paul Clavijo and Juan Vasquez were finally charged with sexual assault and official misconduct in the case.

According to prosecutors, on a Wednesday night in Chicago in late March, the young woman left a friend's apartment in the North Side Wrigleyville neighborhood, intoxicated and upset after an argument.

Clavijo and Vasquez reportedly spotted her sobbing into her phone as she walked down the street and offered her a ride home. She accepted--likely because a ride home with police seemed safer than the 2 a.m. ride on the train. But according to the victim, from the start, the cops appeared to have something else in mind.

Prosecutors allege that when the woman tried to get into the back of the patrol car, the veteran officers--both 38 years old--told her she wasn't allowed to sit in the back seat and would need to sit in front, on one of the cops' laps. Instead of driving her straight home, the on-duty police officers reportedly drove to a liquor store. Vasquez went inside to buy a bottle of vodka, while Clavijo proceeded to sexually assault the woman in the passenger seat of the police SUV.

While many media reports referred to this as the victim "having sex" with Clavijo, Assistant State's Attorney Patti Sudendorf correctly described the incident as an assault, explaining, "The victim believed she could not say no to Clavijo's sexual advances and had to do whatever the police officer asked her to do."

"These are on-duty police officers," stated Jon Loevy, who represents the woman in her civil suit. "They were armed with guns. She was a young woman who was not in a situation where she had a choice."

The two officers then reportedly drove the woman to her apartment in Rogers Park--several miles outside of their jurisdiction--where they followed her inside. They subsequently began drinking and coerced the victim into playing strip poker. While being sexually assaulted by both officers, the woman screamed for help and started banging on her walls in an attempt to wake her neighbors.

Managing to escape, the victim ran out of her apartment, yelling and knocking on her neighbors' doors as she passed. One neighbor woke up and called 911. Another opened his door in time to see one man running down the hall naked, and a second man in uniform walking away.

According to a neighbor who found the victim in the hall, "She was in shock--traumatized." When the neighbor told the victim that the police were on the way, she replied, "It was the cops who did this to me!"

When police arrived on the scene, the young woman was taken to a nearby hospital, and parts of the two officers' uniforms and one of their cell phones were recovered from her apartment. Tests showed that her blood alcohol level was .38 percent--nearly five times the legal limit to drive--a fact that shows the absurdity of claims that the victim could have legally consented to sex.

THE CASE is causing outrage in Chicago--where police misconduct is rampant.

After the victim came forward, it was discovered that weeks earlier, Clavijo had been accused of attacking a different woman. According to reports, in that case, the same two officers picked up a 26-year-old woman in Wrigleyville, gave her a ride home and then asked to come inside to use the bathroom. While Vasquez was in the bathroom, Clavijo reportedly followed the woman into her bedroom and raped her.

Why were these officers allowed to stay on the force? According to the Tribune:

Prosecutors have said the first victim did not immediately report the sexual assault because she was intimidated, but the lawsuit contended she had told investigators before the second alleged sexual assault.

"This other victim reported the rape, yet the Chicago Police Department allowed (Clavijo and Vasquez) to retain their employment as patrol officers, thus enabling them to commit a similar crime...less than one month later," the lawsuit said.

Unfortunately, such crimes are not at all unusual in Chicago--although few reports of misconduct made against the police ever see the light of day, and victims are often pressured against submitting such reports in the first place.

In a case from last summer that only recently received national media attention, police came to the home of Tiawanda Moore and her boyfriend to question them about a domestic disturbance call. The couple was separated for interrogation, and Moore was interviewed by herself in her bedroom. Once they were alone, she alleges, the cop groped her and hit on her--leaving her his personal phone number.

According to Moore, when she went to report the case to internal affairs at the police department on August 18, officers tried to scare her out of it. "They keep giving her the run-around, basically trying to discourage her from making a report," said Moore's attorney Robert Johnson.

After getting frustrated with the lack of respect she was getting, Moore reportedly started to record the exchange on her Blackberry in order to document the lack of police cooperation.

Then, to add insult to injury, when officers discovered Moore was taping them, they arrested her. Moore was charged with two counts of eavesdropping--a Class I felony in the state of Illinois, and one that is being increasingly used by police against people who dare to record officers engaging in misconduct.

Now, Moore faces a possible prison sentence of four to 15 years for recording a police officer--while the department still has not charged the officer who assaulted her. "Before they arrested me for it," Moore told the New York Times, "I didn't even know there was a law about eavesdropping. I wasn't trying to sue anybody. I just wanted somebody to know what had happened to me."

"I'm scared," Moore told the reporter who visited her in jail--where she remains after another domestic dispute with her boyfriend. "I don't know what's going to happen now. I don't want to be in jail. I want to make my parents happy and proud of me."

THESE CASES, which gained greater exposure thanks in part to the budding women's rights movement, have helped bring to light an underlying epidemic of police abuse in Chicago.

According to a study by the University of Chicago Law School, there were over 10,000 reports of police misconduct in the years from 2002-2004. Only 124 of these cases were investigated at all, and shockingly only 19 resulted in any sort of meaningful discipline for the officers involved.

In other words, less than 0.2 percent of reports of police misconduct carried repercussions for the officers involved.

In these two years, there were 111 cases reported of sexual harassment, abuse and rape by Chicago police officers. Of these 111 cases, only two resulted in disciplinary action for the officers involved.

Repeat offenses seem to be the norm--Officer Clavijo's case is far from unique in this way. From 2001 to 2006, there were 662 cops who received 11 or more complaints against them, 33 cops with 30 or more complaints, and four cops with 50 or more complaints. Astonishingly, these officers were all allowed to continue to serve in the same positions, without repercussions, after multiple cases of misconduct had been brought against them.

Cops continue to assault and abuse ordinary people because they think they can get away with it, and they usually do. Such dramatic statistics show that police are not accountable to the communities that they claim to serve.

But it is possible to fight back. For years, activists have been organizing to hold Chicago police--in particular, former Commander Jon Burge and his men--responsible for the torture and wrongful conviction of African American suspects. Although far less than he deserved, Burge was recently sentenced to prison for perjury and obstruction of justice related to the police torture ring. His conviction was only possible because of the work of victims of police brutality, family members and activists.

Now, activists will have to fight to make sure that these latest victims of abuse at the hands of police receive the support they deserve--and that criminal cops are taken off the street once and for all.