Testifying against evictions

reports on a town hall meeting that brought together Cook County residents personally affected by foreclosure and eviction.

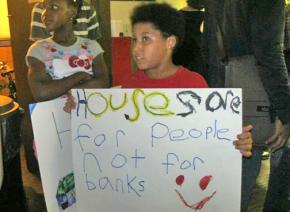

THE CHANT, "Fight, fight, fight! Housing is a human right!" roared around the wood-paneled walls of a 100-year-old union hall on Chicago's Near West Side on August 9.

Nearly 200 outraged Cook County residents directly and indirectly affected by foreclosure and eviction stood shoulder to shoulder to demand that Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle and Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart implement a one-year moratorium on economically motivated foreclosures and evictions in the county.

The two officials were pressured into attending the public meeting after a successful housing action in May that drew more than 300 protesters to the sheriff's office.

The Cook County Sheriff's Department, which oversees Chicago and multiple surrounding suburbs, evicts people from their homes at a rate of nearly 100 a day, as the world's largest banks commit massive foreclosure fraud and get bailed out by the government.

On top of this, evictions are carried out in the shadow of more than 400,000 vacant housing units in Cook County.

These are the facts that fueled the call for a one-year moratorium by residential homeowners facing foreclosure, Section 8 housing residents subject to the eviction whims of profit hungry slumlords, and public housing residents living in underfunded and dilapidated developments that are under constant threat of demolition.

The three groups of residents designated six representatives each to summarize and share their personal struggle against eviction and foreclosure in front of Dart and Preckwinkle. The two officials sat behind large name placeholders in the front corner of the hall.

"PUBLIC HOUSING has made me a better person, we are valuable people, Sheriff Dart," said Sandra Cornwell, a low-income public housing resident living in Lathrop Homes. "We need a moratorium so we can save public housing!"

At Lathrop Homes, there has been a dramatic spike in one-strike evictions--in which a resident is accused of just one infraction and served with an eviction notice--while pressure mounts on residents to take Section 8 vouchers as the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) prepares to implement the next phase of the Plan for Transformation. Low occupancy resulting from the one-strike policy makes it easier for CHA to justify the demolition of developments.

CHA's Plan for Transformation has been destroying public housing developments for more than a decade in Chicago. A one-year moratorium on evictions would allow public housing residents, like the ones living at Lathrop, to continue their fight for safe and affordable housing.

Merlene Robinson-Parsons, a resident of Northpoint, a privatized housing development that accepts Section 8 vouchers, told the crowd:

I have had custody of my 3-year-old grandniece for two years, ever since her 10-month-old sister drowned in a bathtub. If I am evicted from Northpoint, she will be taken by the state. Sheriff Dart, please give us this moratorium so families won't be split up.

Gloria Harris, a senior, said she was kicked out of her home despite being granted a modification. Harris said:

They gave me a modification, and I paid that modification for 10 months. [After] 10 months, they came up with the excuse, "Oh, that wasn't a modification. Here's your money back." I was like, "What? What's this all about."

Of the money allocated from the Illinois Hardest Hit Fund, a $7.6 billion aid program for families in states with the largest home-price declines, only $351 million had been spent to assist just 43,580 U.S. homeowners by the end of June 2012, according to a recent audit.

The Cook County sheriff sat in the corner for most of the evening with his chin resting on his palm. Dart has enforced two moratoriums since 2008 in response to the robo-signing scandal and allegations of predatory lending by the major banks.

After the housing panelists finished their testimony, Dart addressed the audience:

I received advice from the state's attorney [Anita Alvarez] to end the last moratorium because I was told that I was opening the county up to a lawsuit from the [bailed-out] banks...I believe the housing crisis is a horrific tragedy, but I can't re-institute another moratorium without more political support.

Dart sheepishly looked to Preckwinkle, who was sitting to his right and finished, "And by support, I don't necessarily mean from the Cook County board president."

Preckwinkle now had her turn to speak. She missed the first hour of the meeting, citing a conflicting event. As her constituents spoke in the first part of the meeting, she rarely looked up from the table she sat at. When she did, she looked bored. "My job is mostly centered around health care and incarceration issues," she said. "If I were to endorse a moratorium, I would need the support of the other board members."

Of the 13 Cook County board members who were invited to the public meeting, only one showed up. "I am here to listen," Preckwinkle said. "And I can't make any commitments on your demands." The crowd booed and resumed their chants: "What do we want?" "A one-year moratorium!" "When do we want it?" "Now!"

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, one of the emcees of the event, concluded the meeting:

When it comes to making a demand for a moratorium on evictions, activists cannot begin with whether or not it's "realistic." Our goals are based on what is just, not what is possible. If ordinary people who have made historic changes in the past had based whether or not to act on what was realistic and possible, they never would have taken the first step.

The audience erupted in applause and chants, as organizers and attendees made it clear that they would continue their fight for a one-year moratorium on economically motivated evictions in Cook County, despite the unmoved politicians.