Ways of (not) seeing

, an artist and at-large editor for Red Wedge magazine, comments on the latest bizarre turn at CounterPunch, in an article written for Red Wedge.

IN MID-May, CounterPunch published a politically crude article "Of Privilege, Health Care and Tits: Angelina Jolie Under the Knife," by Ruth Fowler. The article attempted to critique an op-ed article by Jolie--about her recent double preventative mastectomy--in order to provide a gender and class analysis of women's health care. The article woodenly counterposed gender and class concerns and then poured a perplexing level of vitriol and scorn on Jolie. Fowler's class anger is certainly understandable--although her targeting is off.

CounterPunch editors, Jeffrey St. Clair and Joshua Frank, then decided to make matters worse when they promoted Fowler's article--and channeled their inner-frat boys--with a mass e-mail reading "Ruth Fowler unsnaps Jolie's bra and exposes privilege, health care and tits."

Things continued to escalate after SocialistWorker.org columnist and CounterPunch contributor Sharon Smith submitted an article critical of Fowler and CounterPunch. Instead of publishing Smith's article and fostering a comradely (and no doubt quite useful) debate about sexism, the relationship of class and gender, health care and the difference between prudishness and opposing the objectification of women, St. Clair and Frank became hysterical.

The latest product of that hysteria, an article titled "Tits, Fits and Vermeers: The Merchants of Shame," was posted on CounterPunch this past weekend. The article consists of a largely unbelievable mise-en-scène, followed by class-baiting, red-baiting, dissembling, half-truths and a truly bizarre discussion of the 17th century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer.

The point of the odd tangent appears to be a mock apology to the Girl with a Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer--who, unlike many of his contemporaries, evidently never painted a naked breast. It is unclear whether this is meant as mere obfuscation--or to argue that since women's bodies have always been subjects in art, St. Clair's detractors are insufferable prudes. Or perhaps it is implied that Vermeer was a prude, and that is why St. Clair is apologizing to him.

I certainly have no problem with the paintings of Johannes Vermeer--although he is not my favorite 17th century Dutch painter. I am still quite fond of the "feverish" work of Rembrandt. Rembrandt was a more interesting painter--in terms of what he did with actual paint--building up the lighter areas of a canvas and washing darks over them like a rain of darkness flooding mountains of light.

The problem here is with St. Clair's supposedly clever, but entirely superficial and confusing, reading of Vermeer's work and the related question of the female form in art.

THERE IS, of course, nothing wrong with depicting the female form. There is also nothing wrong with men and women sexually desiring the female form. There is nothing wrong with depicting this desire in art. Sexuality was part and parcel of art from the beginning. The problem is how these desires are constructed and manipulated in a society that systematically oppresses women and commodifies sexuality.

Regardless, because women have been oppressed for at least 10,000 years, the vast majority of artistic artifacts (mostly produced in that time) reflect this oppression. They reflect (heterosexual) male desires. Women depicted in art, clothed or not, are generally shown as passive, except in regard to these male projections of sexual desire. There are exceptions. The most important exception, in which women are shown as active--in a sense--is in the activities of motherhood, for example, in various madonnas.

Women might be presented as beautiful, ugly, clothed, unclothed, as virtuous, as innocents, as harlots or whores--but they were generally not presented as independent actors. Vermeer is no exception.

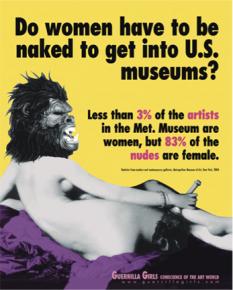

It should go without saying that women were not allowed to become artists--except in rare circumstances. Only in the 20th century did this begin to change--and so far it has changed far too slowly. In 1989, the Guerrilla Girls--an anonymous association of female artists dedicated to challenging "art world" sexism--famously produced the poster at right.

The Guerrilla Girls were not protesting the existence of nudes, but pointing out a sexist contradiction in terms of what was allowed in the high temple of art. Naked women: yes. Female artists: not so much. While things have improved in some quarters, as Ben Davis writes in his new book, 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, the art world is still overwhelmingly male-dominated--even though women make up an increasingly disproportionate number of art school graduates.

St. Clair writes of his visit with the Girl with the Pearl Earring: "She is beautiful and real and present. Her gaze holds you, a chilling goodbye look."

So it is somewhat surprising that St. Clair is apparently ignorant of the implications of the "gaze" in art--a concept articulated by many art historians, by feminists, and by the Marxist art critic John Berger. As Berger put it in Ways of Seeing (1972):

According to usage and conventions which are at last being questioned but have by no means been overcome, the social presence of women is different in kind from that of a man. A man's presence is dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies. If the promise is large and credible his presence is striking. If it is small or incredible, he is found to have little presence. The promised power may be moral, physical, temperamental, economic, social, sexual--but its object is always exterior to the man. A man's presence suggests what he is capable of doing to you or for you....

By contrast, a woman's presence expresses her own attitude to herself, and defines what can and cannot be done to her. Her presence is manifest in her gestures, voice, opinions, expressions, clothes, chosen surroundings, taste--indeed there is nothing she can do which does not contribute to her presence. Presence for a woman is so intrinsic to her person that men tend to think of it as an almost physical emanation, a kind of heat or smell or aura.

To be born a woman has been to be born, within an allotted and confined space, into the keeping of men...A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping...

And so she comes to consider the surveyor and surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity as a woman.

"[M]en act and women appear," Berger argued.

THIS IS clear in many of the female nudes produced from the later Renaissance through the late 19th century. The female figure is passive and defined by her reflection in the male gaze.

It does not follow that these artworks are tainted by mortal sin in some sort of feminist catechism. In fact, Manet's Olympia reflects certain sexist ideas while attempting (within the confines of its time) to challenge elements of those ideas. His nude is not "idealized" (by the bourgeois standards of his day). This led to its scandalous reception at the Paris Salon in 1865--where the model's expression and other elements of the painting indicated that she was a prostitute. Manet's gesture stripped the actuality of the artistic nude (as a commodity for the male gaze) from pretense.

Nevertheless, these works do not escape the logic of the gaze. To say that Goya's Naga--or Vermeer's Girl with the Pearl Earrings--proves something about the use (or misuse) of the female image is to beg the question. The meaning (in terms of gender oppression) is in the contradiction between the presentations of the female and male.

The heyday of easel painting produced three main variations of painting--all of which were purchased by the bourgeois collector: portraits, landscapes and history/mythological/religious painting. The images of men are almost always of the triumphant bourgeois (or heroic substitute), perhaps at home, perhaps at study, often overlooking his wealth or holdings, or triumphing in battle, etc.

Landscapes were the least popular in the early art market--perhaps the bourgeois sensed how they might come to include the poor, or perhaps they were threatened by the artist's fetish for nature, for which the rich merchants had utilitarian designs.

Regardless, while men acted on the world, women were the objects of men's actions and desires. This is why titillating stories, "naughty pictures" and innuendo are not merely titillating stories, "naughty pictures" and innuendo. It is also why sentimentality is not just sentimentality. The terrain on which these things grow is uneven and unequal. It is one in which all sexuality is commodified--but female sexuality is additionally oppressed for being female.

NO SERIOUS artist coming of age in the past few decades has failed to confront this issue--positively or negatively. One doesn't have to refer to overtly feminist artists like Mike Kelley--who used traditionally "female" materials like yarn to make cloth phalluses--to see that most contemporary artists have eschewed the unthinking presentation of female nudes and passive women.

It is not that artists have suddenly become prudes. Many have simply become conscious of the relationship of sexism to the gaze.

This is not to say that sexism (and crude objectifications of women) don't persist in contemporary art. They do--as the controversy surrounding Marina Abramovic's Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) "Gala" showed in 2011. Abramovic situated naked female models as centerpieces for a museum fundraiser. These women's bodies literally became objects for a bourgeois gaze.

As the choreographer Yvonne Rainer protested:

After observing a rehearsal, I am writing to protest the "entertainment" about to be provided by Marina Abramovic at the upcoming donor gala at the Museum of Contemporary Art where a number of young people's live heads will be rotating as decorative centerpieces at diners' tables and others--all women--will be required to lie perfectly still in the nude for over three hours under fake skeletons, also as centerpieces surrounded by diners.

On the face of it the above description might strike one as reminiscent of Salo, Pasolini's controversial film of 1975 that dealt with sadism and sexual abuse of a group of adolescents at the hands of a bunch of postwar fascists. Though it is hard to watch, Pasolini's film has a socially credible justification tied to the cause of anti-fascism. Abramovic and MoCA have no such credibility--and I am speaking of this event itself, not of Abramovic's work in general--only a questionable personal rationale about the beauty of eye contact and the transcendence of artists' suffering.

At the rehearsal the fifty heads--all young, beautiful, and mostly white--turning and bobbing out of holes as their bodies crouched beneath the otherwise empty tables, appeared touching and somewhat comic, but when I tried to envision 800 inebriated diners surrounding them, I had another impression.

I myself have never been averse to occasional epatering of the bourgeoisie. However, I can't help feeling that subjecting her performers to possible public humiliation and bodily injury from the three-hour endurance test at the hands of a bunch of frolicking donors is yet another example of the Museum's callousness and greed and Ms Abramovic's obliviousness to differences in context and some of the implications of transposing her own powerful performances to the bodies of others. An exhibition is one thing--again, this is not a critique of Abramovic's work in general--but titillation for wealthy donor/diners as a means of raising money is another.

IF SEXISM continues in "visual art," it runs rampant in popular culture. Advertisements, broadcast television and basic cable, and film are rife with unreflective presentations of the female intended for the gaze. This is not even to mention the porn industry. The mainstream culture constantly reproduces and reinforces this dynamic because of capitalism's need (as capital) for women to occupy a different status than men--making all women bear personal responsibility for the reproduction of species.

Even when there is an artistic reason for the female nude, the artist and viewer must seriously consider what this means in a sexist society. For example, a female actor in HBO's Game of Thrones--a very well-written and layered piece of television based on George R.R. Martin's novels--recently protested that she would no longer do nude scenes. The actor's lament that she would rather be known for her acting skill rather than her breasts is entirely justified in an industry that gave a platform to Seth McFarlane at the Academy Awards.

These are not abstract concerns important to a cultured minority. The cultural construction of gender is closely related to the material oppression of women and sexual minorities--rape, unequal pay, over- and under-representation in various industries, loss of reproductive rights, lack of child care, lack of elder care, lack of employment and housing rights, etc. The passive female image--as the focus of male desire or as model of virtue--is certainly no defense against accusations of sexism.

The answer to this--in terms of culture--is not an easy one. Puritanism is the cousin of cruder sexisms. It provides women (and, by extension, men) with the choice of virgin or whore, which is no choice at all. Moreover, sexuality is an ancient and primal force. It is both intensely serious and often unserious. It has both a scientific and spiritual side in that it can be understood and can't be fully understood at the same time. Our understanding of (or more accurately, our participation in) these factors is constantly upset by the distortions of sexist society.

Art that aspires to deal with sexuality and gender must therefore deal with all these things. It is no easy task. This is because art must aspire to represent this world (which is sexist), aspirations for a better world (that isn't) and things that cannot be represented at all (whatever reality might lurk behind the greater contradictions of sexuality--contradictions that exist beyond class society).

The task for activists who oppose sexism, however, is somewhat more straightforward. Clear manifestations of oppression must be opposed. I do not believe that it was ever the intention of CounterPunch or Ruth Fowler to do anything sexist. However, CounterPunch's circling of the wagons at the hint of criticism betrayed a misunderstanding of the scope and scale of women's oppression--a misunderstanding confirmed by Jeffrey St. Clair's odd invocation of a 17th century Dutch painting.