The moment of the March

When a quarter million people came to the capital for the 1963 March on Washington--the largest national demonstration to that point--it was a new high point for the civil rights struggle. But it came amid increasingly intense battles to end segregation in the South--particularly in Birmingham, Ala., where activists' commitment to the principles of nonviolence put forward by Martin Luther King were put to the test by the violence of segregationists.

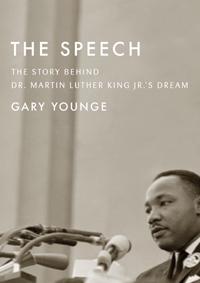

Just in time for the 50th anniversary of the march, Guardian columnist has written The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s Dream. In this excerpt, reprinted with permission, Younge describes the struggles that set the stage for the march.

ON FEBRUARY 1, 1960, seventeen-year-old Franklin McCain and three Black friends went to the whites-only counter at Woolworths in Greensboro, North Carolina, and took a seat. "We wanted to go beyond what our parents had done....The worst thing that could happen was that the Ku Klux Klan could kill us...but I had no concern for my personal safety. The day I sat at that counter I had the most tremendous feeling of elation and celebration," he told me. "I felt that in this life nothing else mattered....If there's a heaven I got there for a few minutes. I just felt you can't touch me. You can't hurt me. There's no other experience like it."

A few years later, in May 1963, in Birmingham, Alabama, a burly white police officer attempted to intimidate some Black schoolchildren to keep them from joining the growing antisegregation protests. They assured him they knew what they were doing, ignored his entreaties, and continued their march toward Kelly Ingram Park, where they were arrested. A reporter asked one of them her age. "Six," she said, as she climbed into the paddy wagon.

The following month in Mississippi, stalwart civil rights campaigner Fannie Lou Hamer overheard Annell Ponder, a fellow campaigner, being beaten in jail in an adjacent cell.

"Can you say yes, sir, nigger? Can you say yes, sir?" the policeman demanded.

"Yes, I can say yes, sir," replied the protester.

"So say it."

"I don't know you well enough," said Ponder, and then Hamer heard her hit the floor again. The torture continued like this for some time, with Ponder praying for God to forgive her tormentors.

Hamer later recalled that when she next saw Ponder, "one of her eyes looked like blood and her mouth was swollen."

"All books about all revolutions begin with a chapter that describes the decay of tottering authority or the misery and sufferings of the people," wrote the late Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski in Shah of Shahs. "They should begin with a psychological chapter, one that shows how a harassed, terrified man suddenly breaks his terror, stops being afraid. This unusual process demands illuminating. Man gets rid of fear and feels free."

THE PERIOD preceding Martin Luther King's speech at the March on Washington was one such chapter. Until that point, there had, of course, been many fearless acts by antiracist protesters. But in that moment, the number who were prepared to commit them reached a critical mass. "In three difficult years," wrote the late academic Manning Marable in Race, Reform and Rebellion, "the southern struggle had grown from a modest group of Black students demonstrating peacefully at one lunch counter to the largest mass movement for racial reform and civil rights in the twentieth century."

In May 1963, the New York Times published more stories about civil rights in two weeks than it had in the previous two years, points out Drew Hansen in The Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Speech That Inspired a Nation. According to the Justice Department, during the ten-week period following Kennedy's national address on civil rights in June, shortly before King's speech, there were 758 demonstrations in 186 cities, resulting in 14,733 arrests. Such were the conditions that made the March on Washington possible and King's speech so resonant. As Clarence Jones would later write in Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech That Transformed a Nation: "Text without context, in this case especially, would be quite a loss."

The context was global. Two days after McCain made his protest in Greensboro, the British prime minister, Harold Macmillan, addressed the South African Parliament in Cape Town with an ominous warning. "The wind of change is blowing through this continent," he said. "Whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact."

Some, including his immediate audience, did not like it at all. But as the decade wore on, that wind became a gale. In the three years between Macmillan's speech and the March on Washington, Togo, Mali, Senegal, Zaire, Somalia, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Chad, Central African Republic, Congo, Gabon, Nigeria, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, Tanganyika, and Jamaica all became independent. Internationally, nonracial democracy and the Black enfranchisement that came with it were the order of the day. The longer America practiced legal segregation, the more it looked like a slum on the wrong side of history rather than a shining city on the hill. "The new sense of dignity on the part of the Negro," argued King, was due in part to "the awareness that his struggle is a part of a world-wide struggle. He has watched developments in Asia and Africa with rapt attention....[It] is a drama being played out on the stage of the world with spectators and supporters from every continent."

Those places that clung to rigidly codified racism would be increasingly reduced to a rump: South Africa, Namibia, Rhodesia, and Mozambique in Africa; the Deep South in the United States--that region W.J. Cash described, in The Mind of the South, as "not quite a nation within a nation, but the next thing to it." From here on, white privilege could be explicitly defended only by resorting to ever more heinous acts of violence that prompted, in response, ever more determined acts of defiance.

"The year before [the March on Washington] had been like a second Civil War," wrote John Lewis in his autobiography, Walking with the Wind, "with bombings, beatings and killings happening almost weekly. A march would be met with violence, which would cause yet another march, and so on. That was the pattern."

As the segregationists' violence escalated, so did the militancy of Black activists. Earlier that year King had been heckled in Harlem with the chant "We want Malcolm, we want Malcolm."

As long as there has been racism in America, there has been a rift between those who sought to fight alongside whites for equality and integration on the one hand, and on the other Black nationalists, who argued that Blacks should organize separately from whites to establish an autonomous homeland either within the United States or in Africa. For some, the issue was tactical, for others, a matter of principle, providing for plenty of overlap between the two. At this time, Malcolm X was the most prominent Black nationalist and a member of the Nation of Islam, a Muslim sect that did not believe in nonviolence or integration.

"It's just like when you've got some coffee that's too black, which means it's too strong," Malcolm X once said, explaining his wariness about working with white people. "What do you do? You integrate it with cream, you make it weak. But if you pour too much cream in it, you won't even know you ever had coffee. It used to be hot, it becomes cool. It used to be strong, it becomes weak. It used to wake you up, now it puts you to sleep."

BY THE summer of 1963 some African Americans were losing hope that white America would ever accommodate their most basic demands for human rights. "There were many in the summer of '63 who did [agree with Malcolm X]--more it seemed every day," wrote Lewis. "I could see Malcolm's appeal, especially to young people who had never been exposed to or had any understanding of the discipline of nonviolence--and also to people who had given up on that discipline. There was no question Malcolm X was tapping into a growing feeling of restlessness and resentment among America's blacks."

On May 13, John F. Kennedy's principal Black adviser, Louis Martin, wrote a memo to the president, explaining: "As this is written, demonstrations and marches are planned. The accelerated tempo of Negro restiveness . . . may soon create the most critical state of race relations this country has seen since the Civil War." A month later, the U.S. ambassador to India, J. K. Galbraith, urged: "This is our last chance to remain in control of matters."

While such warnings were portentous, this was no existential threat. The American state was not about to be overthrown. Nonetheless, the moment represented a thoroughgoing assault against one of the fundamental pillars on which the nation had been established: white supremacy.

One of the central aims of the civil rights movement was to create a crisis in the polity. This strategy was explicitly laid out by James Farmer, the head of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1961 during the Freedom Rides, when a racially mixed group of protesters went through the South on buses with Blacks sitting at the front and whites at the back. "What we had to do," said Farmer, "was make it more dangerous politically for the federal government not to enforce the law than it would be for them to enforce federal law. We felt we could count on the racists of the South to create a crisis so that the federal government would be compelled to enforce the law."

The white citizenry of the South was only too happy to oblige. When one bus rolled into Anniston, Alabama, it was chased up the highway and firebombed. When another arrived in Birmingham, it was met by men wielding baseball bats and lead pipes. These attacks took place with the active collusion of the region's political class. Alabama's governor, George Wallace, took office in the year of King's speech. Shortly before he did so, his attorney general, Richmond Flowers, warned him of the predictable consequences of following through on the defiant segregationist rhetoric that had been a hallmark of his election campaign. "Look George, you gonna be whupped all through the courts. And when you're whupped in the courts, the Klan's gonna come out on the streets and the killing's gonna start. You know that's what's gonna happen."

Wallace told him, "Damnit, send the Justice Department word, I ain't compromising with anybody. I'm gonna make 'em bring troops into this state."

A populist and a demagogue, Wallace aimed not to score a substantial victory but to perform resistance; a strategy that, a century after the Confederate defeat in the Civil War, had particular appeal among a section of southern whites. "Wallace's political psychology essentially derives from the Southern romance of an unvanquished and intransigent spirit in the face of utter, desolate defeat," argues Marshall Frady in Wallace.

What Farmer could not have predicted, however, was just how reluctant the federal government under Kennedy would be to intervene when faced with these crises. This was partly because the members of his administration didn't fully comprehend the enormity of what was happening. JFK's brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, evidently struggled to grasp the indignity of segregation. "They can stand at the lunch counters. They don't have to eat there. They can pee before they come into the store or the supermarket." Nor was he particularly sympathetic to Black people's impatience with the slow pace of change. "Negroes are now just antagonistic and mad, and they're going to be mad at everything. You can't talk to them....My friends all say [even] the Negro maids and servants are getting antagonistic."

The president, meanwhile, was worried about alienating a key sector of his electoral base: white southerners. The Democratic Party at that time was a curious coalition of southern segregationists, northern liberals, and those African Americans who were allowed to vote. The Black vote had been crucial to Kennedy's narrow victory against Nixon in 1960, but so too were southern whites. Both Wallace and King had voted for Kennedy.

From the outset, the president decided the wisest strategy was to avoid coming between them. "Kennedy now worried that any attempt to push Southern Democrats on civil rights was likely to produce a backlash," writes Nick Bryant in The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality. "If we drive...moderate southerners to the wall with a lot of civil rights demands that can't pass anyway," Kennedy told an aide, "then what happens to the Negro on minimum wages, housing and the rest?"

But in the absence of federal intervention the crisis didn't disappear; it deepened. African Americans became more determined; segregationists became more desperate. "The crisis," argued Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks, "consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born."

Until the summer of 1963, when King delivered his speech, even though the health of the old segregated polity in the South was clearly failing, the birth of a new integrated one had yet to be induced. Eventually the Kennedy administration was forced to play midwife. It had no choice.

By the time of the March on Washington, the civil rights movement had raised acute questions of power: Who has it? Who wants it? How do you get it? How do you keep it? The answers would be delivered in the bluntest fashion. Governors personally blocked schoolhouse doors, cities were put under martial law, National Guard troops were federalized and dispatched, children filled jails, protesters were killed. In short, the fundamental ability and right of the state to maintain law and order became an open question, assaulted at every turn from all directions.

In the South, segregation had been the norm for more than two centuries, with a brief break during Reconstruction after the Civil War. While it had always been resisted, generations of both Blacks and whites, not to mention officials both federal and local, had grown accustomed to it. "Who hears a clock tick or the surf murmur or the trains pass?" asked James Kilpatrick, editor of the New Leader, of Richmond, Virginia, in The Southern Case for School Segregation in 1962. "Not those who live by the clock or the sea or the track. In the South, the acceptance of racial separation begins in the cradle. What rational man imagines this concept can be shattered overnight?"

Now, with the status quo openly challenged and brutally defended, long-held allegiances were tested and positions polarized. Key players who had learned to live with segregation--the federal government, business interests, liberal whites, conservative Blacks--were forced to reckon with the arrival of a new order. And fissures opened up not just between these various interested parties but also within them as events tested their ability to accommodate, negotiate, and confront this impending transformation, drawing sharp distinctions at each juncture between those who ostensibly held power and those who actually wielded influence.