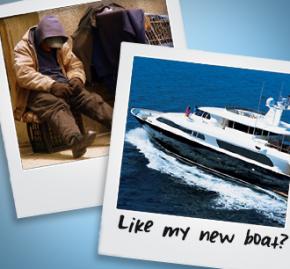

Snapshots of inequality

compiles the statistics to show how inequality has grown worse.

IT GOES without saying that capitalism causes economic inequality.

This is actually a point of pride for defenders of the system--they believe that the free market thrives because the deserving few are rewarded. The Marxist critique of capitalism takes the exact opposite position: The tiny few who live so well compared to the rest of us are completely undeserving of their immense wealth--they amassed their fortunes through systematic theft of the labor of the working majority in society.

But we also know that capitalism goes through periods in which economic inequality is more extreme and less so. So what kind of moment are we looking at now? What is the shape and contour of inequality in the U.S. today, six years after the recession that cratered in 2008?

If you set out to answer these questions, here are some of the snapshots of American inequality you would see:

Belief and Reality

People in the U.S. largely believe their society to be far more equitable than it actually is.

A study conducted in 2010 compared the actual distribution of wealth in the U.S. to: first, what Americans think the distribution of wealth is; and second, what they think it ought to be. The results are telling.

What is the actual distribution of wealth? The richest 20 percent of Americans owns nearly 85 percent of the country's wealth. The richest 40 percent own just about 95 percent. On the other end of things, the poorest 20 percent of Americans own 0.1 percent.

But people in the U.S. believe the wealth gap is far smaller than it is. They estimate that the richest 20 percent owns about 55 percent of the country's wealth. On the other side of the spectrum, people estimate the poorest 20 percent to own about 5 percent of the wealth. Asked what they think would be ideal, people want a far more equitable distribution of wealth. Ideally, they think the richest 20 percent should own just over 30 percent of the wealth, and the bottom 20 percent should own about 11 percent.

Productivity and Wages

Paul Ryan and the Republicans have turned up the volume on their victim-blaming rhetoric lately (and by the way, the Democrats aren't much better). Their explanation for the persistence of poverty: "The key is work," "It's all about working" and, of course, the dreaded "cultural tailspin" of generations of young Black and Brown men who supposedly understand the value and importance of work.

Not only do these comments demonstrate the Republicans' deep-seated racism, but they are profoundly disconnected with reality in terms of providing an explanation for poverty.

Since the 1970s, the productivity of U.S. workers has only increased while hourly compensation has remained more or less the same. This yawning gap between productivity and wages benefits the richest 1 percent, which owns 42 percent of the country's financial wealth. The bottom 80 percent of the population, by contrast, owns barely 5 percent.

Taken together, these figures tell us that U.S. workers have worked harder and harder over decades, while gaining nothing more in wages--in fact, they have lost ground as a consequence of the Great Recession--nor in the financial wealth their labor produces.

This is not an accident--the increase in productivity alongside a stagnation in wages is a direct consequence of neoliberal policies having been implemented throughout the period.

It is a straight-up fabrication and an insult for political and business leaders to claim that the working-class majority or any section of it isn't working, or isn't working hard enough. The opposite is, in fact, the case. There is a historic robbery-in-progress undertaken by American business--the corporate boardrooms are the site of the real culture of freeloading.

How Does the U.S. Stack Up Internationally?

The mainstream media and leaders of both political parties insist that the U.S. is the "land of opportunity," with a strong and functional "engine of prosperity" that ultimately benefits the whole population.

Indeed, "prosperity" does define the U.S. ruling class, but what about the rest of America? Where does the U.S. rank among other countries in terms of equality? Probably not first or second, surely--but maybe fifth or tenth?

On a list of 137 countries, ranked in order of their Gini coefficients--a statistical measure of the distribution of household income in a country on a sale of 0 to 1, where 0 is perfect equality and 1 is maximum inequality--the U.S. isn't even close to the top 10.

Sweden tops the list as the most equal country, with a Gini coefficient of 0.23. The most unequal countries are Lesotho, South Africa and Botswana, all with ratios of 63 and over.

The U.S.? It's a lot closer to Lesotho than Sweden. The U.S. is in 97th place, with a Gini coefficient of 0.45, surrounded by Bulgaria and Uruguay on one side, and the Philippines and Cameroon on the other.

Social (Im-)Mobility

At least the U.S., for all its drawbacks, remains one of those countries where those who work hard can "pull themselves up by their bootstraps" and climb the socio-economic ladder. However wealthy the U.S. ruling class may be, at least it's possible for even the poorest individuals to rise into the elite, with enough hard work and perseverance.

Right?

Wrong.

The technical term used by economists to describe the ease or lack of ease for people to climb to a higher-earning status is "social mobility.

According to a 2006 study done by researchers the Institute for the Study of Labor in Bonn, Germany, sons born to a father in the poorest 20 percent of the population were twice as likely to stay in the bottom 40 percent in terms of income. Only one in five sons of fathers in the poorest 20 percent made it to the upper 40 percent. The pattern is similar for daughters.

Economists have plotted social mobility--or to use another term for this dynamic, "intergenerational earnings elasticity"--on a 0 to 1 scale, like the Gini coefficient. Once again, the U.S. ranks on the same end of the scale with the most unequal countries--they are, unsurprisingly, the least socially mobile as well.

Incarceration in the Land of the Free

Inequality rears its head in all aspects of society. It very visibly affects the nature of the U.S. prison system. Bear in mind that all this is taking place in a country that already incarcerates more of its population than any country in the world, so those caught on the wrong end of the inequality in the prison system are enduring the worst of the worst by this measure.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, one in 106 white men over age 18 are incarcerated each year. For Latino men in this age group, the figure is one in 36. For African American men, it is one in 15--making it seven times more likely a Black man will go to jail than a white man. The same racial disparity exists for women.

Accordingly, Michelle Alexander notes in her book The New Jim Crow that more Black men are in prison today or under the supervision of the criminal justice system than there were slaves in the U.S. in 1850.

The cost of keeping someone in a federal prison for a year is estimated at between $21,000 and $33,000. At the higher figure, that's more than triple what the U.S. spends per pupil per year in secondary schools--$10,560 in 2011.

The Gendered Wage Gap

Between 1972 and 2000, the pay disparity between women and men shrank slowly. Since then, the shrinking has stopped almost completely.

Women's median annual earnings as a percentage of men's has hovered around 77 percent for the past 12 years. In nearly every occupation, women make less than men for doing the same work--and according to every category into which data can be organized.

The pay gap fluctuates depending on where you happen to live. In Washington D.C., women on average were paid 90 percent of what men were paid in 2012. In Wyoming, women were paid 64 percent of what men made.

Women of color have it the worst. Compared to white men, Black women were paid 64 percent, American Indian women were paid 60 percent and Latino women were paid 53 percent.

There are two standard responses to these statistics. One is that women tend to be over-represented in occupations that pay less. But remember that women are paid less across the board, including within the same occupations. But the gendered pay gap exists even for women who don't have children--they are paid just over 80 percent of what men make. Moreover, women have become a larger and larger part of the workforce since the 1970s, despite the burden of primary responsibility for child-rearing.

The Average Worker and the "Average" CEO

Since the 1970s, the gap between the wage of an average worker and the total compensation of the CEOs of America's biggest corporations has grown into a Grand Canyon.

The ratio of CEO pay to the average pay of a worker climbed from 53.3-to-1 before the 1990s got underway to reach a peak of 411.3-to-1 in 2000. Ever since, the ratio has fluctuated in the 200- to 300-to-1 range.

In 2012, the ratio stood at 273-to-1, with average compensation for CEOs at the 350 largest corporations running at $14.1 million a year.

If you were to increase by 50 percent the paychecks of the nearly 1.1 million people working full-time at federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, their total income wouldn't add up to the bonuses alone given to 165,200 Wall Street employees in 2013 ($26.7 billion).

Even the financial press questions what today's CEOs are doing to earn so much more than their counterparts from 25 years ago. But the reality is that these modern-day robber barons do little of real value compared to the millions of people whose jobs are much more demanding, and who live even more demanding lives.

The Decline of Organized Labor

At one point in history, there was an important factor countering the inevitable tendency of capitalism toward inequality--the power of U.S. unions to compel higher pay, decent benefits, reasonable hours and workplace safety for a significant part of the U.S. working class.

But like so much else for working people, union power has declined compared to the power of business. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the percentage of wage and salary workers who were members of unions in 2013 stood at 11.3 percent. Among private-sector workers, the percentage was a lowly 6.7 percent.

THESE ARE some of the stark facts about inequality in the richest country in the history of the world.

On the one hand, the U.S. does badly, particularly among industrialized countries, in terms of economic inequality, making it a terrible example for anyone interested in making the world a more equal and easier place to live. But precisely because of its staggering inequality, the U.S. ruling class provides a model to the rulers of the rest of the world for imposing the kind of policies that make inequality worse than ever.

This is not an abstract question. A recent study, funded in part by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, concludes that humanity is threatened not only by runaway climate change but the uneven distribution of wealth around the world.

It's not enough to familiarize yourself with the enraging litany of statistics presented here. It's not enough to know that the world's main superpower is among the least equal society among its comparable peers. It's not enough to understand how Corporate America and the U.S. political leaders who serve it export inequality around the world.

Instead, we need to organize for a different society that eliminates the vast gap between rich and poor by confronting the system that perpetuates the chasm: capitalism.