A thousand points of lies

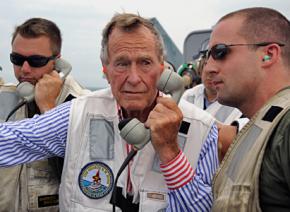

George H.W. Bush's presidency was feted at a 25th anniversary celebration earlier this month--but remembers crimes and disasters Bush Sr. is responsible for.

IF MAINSTREAM historians feel a strong urge to turn revolutionaries into demons or harmless icons, they also feel an equally strong need to turn failed presidents into national heroes.

Is it George H.W. Bush's turn?

If so, will historians manage to massage away the image of Bush Sr. as an out-of-touch patrician who couldn't understand the most basic needs of working people during the recession of the early 1990s?

It appears that they're going to try.

Last weekend, the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library in College Station, Texas, hosted a series of events to commemorate his presidency. A new statue of Bush was unveiled, and the surviving members of his foreign policy team joined him to laud--not surprisingly--his alleged foreign policy achievements.

They avoided any discussion of his disastrous 1992 re-election campaign--but who among us who was alive and politically conscious can forget it?

Remember how he famously couldn't answer such simple questions as "What is the price of a gallon of milk?" During another campaign stop at a supermarket, he was genuinely amazed by the magic scanner used to ring up groceries--revealing that he hadn't been in a supermarket in a decade, if ever. How about the time when Bush grew bored during one of the candidates' debates on the economy and looked at his watch in frustration, as if to say, "When am I done with this bullshit?"

Or when he was hit by a pesky question from young African American women, who asked, "[H]ow can you honestly find a cure for the economic problems of common people, if you have no experience in what's ailing them?"

He just couldn't answer her. "Maybe, I'm getting it wrong?" Bush stuttered. "Are you suggesting that if somebody has means, that the national debt doesn't affect them?...I'm not sure--help me with the question, and I'll try to answer it."

Of course, no one could help Bush with the question, because he truly couldn't understand the lives of real people enough to answer it.

LONG BEFORE Bush's epic failures on the 1992 campaign trail, however, he was a total failure for the majority of people in the U.S.

In 1988, he emerged from the shadow of Ronald Reagan and became the Republican presidential nominee for the fall election. He faced Michael Dukakis, the sitting governor of Massachusetts.

Bush began the campaign behind Dukakis by double-digit margins in opinion polls taken in the late summer of 1988. That's when he decided to unleash his campaign attack dog Lee Atwater. It was one of the most racist national political campaigns in modern U.S. history.

The late Atwater was a master of delivering the new coded racist messages of the post-civil rights era--bigotry toward African Americans was no longer expressed in terms of white supremacy, but couched in messages about "crime" and "welfare dependency"--in campaign attacks ads. Atwater produced the "Willie Horton" and "Revolving Door" commercials that purported to be about Dukakis' record as governor, but in reality smeared Black men as habitual rapists and murderers, and lifelong hardened criminals.

Massachusetts' relatively liberal prison and furlough policies were, in fact, modeled on those developed by Ronald Reagan was governor of California--but in Atwater's hands, they became sinister examples of a "soft Northeast liberal" who was making the streets of America unsafe.

The Bush campaign managed to spread rumors about Dukakis' alleged mental health problems, implied that he was unpatriotic and demonized his support for civil liberties and opposition to the death penalty. He's "a card-carrying member of the ACLU," Bush growled.

It was a filthy campaign, and the hapless Dukakis team seemed bewildered by the tsunami of attacks on them. Bush ended up trouncing Dukakis in the fall election, and Dukakis disappeared into political oblivion.

AFTER HE was elected, Bush went on a public relations offensive to try to soften his image. He said he was going to be the "environmental president," the "education president" or whatever else seemed to resonate in White House polling. He made an appeal to volunteerism to cure America's social problems, describing community-based initiatives as "a thousand points of light."

But all of this was a cover for a continuing assault on the legacy of the 1960s social movements--that is, those social programs and policies, such as affirmative action, that had survived Ronald Reagan's axe. Bush took the offensive by attacking what he called "political correctness." "Political extremists roam the land, abusing the privilege of free speech, setting citizens against one another on the basis of their class or race," Bush told a graduating class of students at the University of Michigan in May 1991.

The effect was a call for a new McCarthyism on U.S. college campuses. Women's advocacy groups and centers, anti-racist initiatives, and liberal and left-wing professors found themselves under scrutiny or even siege by college administrators, the media and right-wing students after Bush's call to action.

In the summer of 1991, Bush nominated Clarence Thomas, a right-wing African American judge, to replace retiring Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall, a hero to an older generation of African Americans for his long years as an NAACP attorney and one of the most consistent liberal voices on the Court.

Bush nominated Thomas to undo Marshall's legacy--but Thomas' confirmation hearing blew up after Anita Hill, an African American attorney and former coworker of Thomas, spoke up. She gave credible, painful testimony of the sexual harassment she endured from Thomas. It was the first serious national debate about sexual harassment in the workplace.

Thomas came close to withdrawing his nomination, but the Bush White House mobilized its attack machine and had Thomas play the victim. Hill was viciously attacked, in the hearing room and outside it, though her testimony was hard to impeach. Thomas survived the hearing and won confirmation by a 52-48 margin, one of closest votes for a Supreme Court justice in history.

For the next quarter of a century, Thomas and his evil and much shrewder twin, Antonin Scalia, have been two sure votes for every reactionary ruling of the Supreme Court.

WHAT ABOUT Bush's supposed foreign policy triumphs?

Little more than a year after being elected president, Bush ordered the invasion of Panama, a Central American country than had existed as a semi-colony of the U.S. for most its history. The goal was to topple Panamanian dictator Col. Manuel Noriega, a longtime CIA asset who was completely tied up with the international drug trade. This was well-known and tolerated by the U.S. for years--including while the CIA was run by one George H.W. Bush under President Gerald Ford.

But like other U.S.-backed tyrants before him and after, Noriega began to defy his masters in Washington. In December 1989, the U.S. military carried out the ironically named "Operation Just Cause" and easily dealt with Noriega's weak military. During the assault, the U.S. destroyed large sections of working-class neighborhoods in Panama City--for no clear reason given the ease with which the Panamanian Army was conquered.

The U.S. put in power men more to their liking. Predictably enough, corruption and drug dealing became even worse after Noriega was toppled, as the award-winning documentary The Panama Deception shows.

But it's the first Gulf War against Iraq that is almost always held up as the crowning achievement of Bush Sr.'s presidency.

The war is remembered as a triumph for international diplomacy and the Pentagon. For the war planners and diplomats, this may be so--but from the perspective of the Iraqi people, and many other peoples around the world, it was disaster and one of the gravest crimes of the U.S. government in the latter half of the 20th century.

On August 2, 1990, Saddam Hussein, the dictator of Iraq and hitherto ally of the U.S., invaded neighboring Kuwait, a small oil kingdom and police state controlled by the Al-Sabah family, also a U.S. ally. There were longstanding disputes between the two countries over adjoining oilfields--Hussein invaded and annexed Kuwait to Iraq.

Alarm bells went off in Washington. Hussein's move against Kuwait was seen as a threat to U.S. control over the world's main oil reserves and their distribution around the globe. While the Bush White House tried to paint this war for oil in nobler terms, former Assistant Secretary of Defense Lawrence Korb put it succinctly, "If Kuwait grew carrots, we wouldn't give a damn."

Bush succeeding in putting together a large international coalition in favor of military intervention, but it was U.S. forces that carried out the war. Bush sent a massive armed force to the Saudi desert, and after Hussein refused to meet a unilaterlly imposed deadline for withdrawal from Kuwait, U.S. Air Force and Navy warplanes pummeled Iraq in one of the most brutal air assaults in world history.

After three weeks of bombardment that caused untold numbers of civilian deaths and injuries, U.S. ground forces invaded and retook Kuwait and most of southern Iraq, taking few casualties. The U.S. killed hundreds of Iraqi soldiers, if not more, in a "bulldozer" assault--the Iraqis were buried alive in their trenches by armored bulldozers. Many of the that survived were slaughtered by the thousands along the so-called "Highway of Death," as U.S. warplanes opened fire on every vehicle between Kuwait and the Iraqi capital of Baghdad.

In the closing days of the war, Bush called on the people of Iraq to rise up and overthrow Hussein. But when the Kurds in northern Iraq and the Shia in southern Iraq responded, U.S. forces stood aside and watched as the remnants of the Iraqi army slaughtered the rebel forces.

In the aftermath of the war, both Iraqi civilians and U.S. soldiers suffered from a variety of illnesses--it turned out that that they had been guinea pigs for the testing of a new generation of weapons, including those using depleted uranium, which was used to harden artillery shells.

By the war's end, Bush's popularity soared to 90 percent approval ratings. But the public euphoria over the quick and victorious war wore off nearly as quickly. The worsening U.S. economy doomed Bush's proclamation of a "New World Order." The 1992 Los Angeles Rebellion--riots and protests sparked by the not-guilty verdict for LA cops who beat Rodney King half to death--was the most obvious symbol of political discontent simmering below the surface. Bush became the first president to win a war and lose an election.

Many people today will see the barbarism of Bush's son, George W. Bush, who followed his father into the White House in 2001, as far worse than his father. That may be so--but we shouldn't forget that the crimes of the son began with those of the father.