Greenlee’s blueprint for revolt

describes the legacy that writer Sam Greenlee leaves behind.

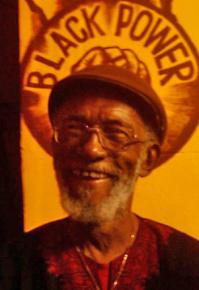

SAM GREENLEE died on May 21. A novelist, filmmaker, poet, community activist and revolutionary, he spent most of his life living on the South Side of Chicago.

Greenlee is rightfully best known for his 1973 movie The Spook Who Sat by the Door, based on his 1969 book of the same name. It is a singular movie, set in a world where an organized Black guerrilla revolt erupts--it was made at a time in U.S. history when that seemed possible. It ran for three weeks, only to largely disappear, and was available only on bootleg until it was reissued in 2004.

Greenlee worked for the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) from 1957 to 1965, serving in Iraq, Pakistan, Indonesia and Greece. He described his work in the USIA as being a propagandist:

I sold the United States like toothpaste. [We] used all forms of media--journalistic releases, pamphlets, magazines...poets, playwrights, orchestras, jazz musicians...to put a good face on American culture. In both Iran and Iraq, the USIA [produced] propaganda for the Iraqis and the Iranians to support the king in Iraq and the shah in Iran.

Greenlee's other book, Baghdad Blues, is his firsthand account of Iraq prior to and during the 1958 revolution against the monarchy. The novel exposes the incompetence, insularity and racism of the U.S. government. One gets the impression that very little has changed in the ensuing 56 years.

THE SPOOK Who Sat By the Door is one of the best of the '70s Black cast films, known as blaxploitation movies. It makes an unapologetic call for revolution. It should be seen as a companion movie to The Battle of Algiers.

Spook attempted to be a blueprint for how to build a guerrilla movement in the U.S., with large sections of the movie devoted to descriptions of tactics and organizational structures of successful underground movements. Most blaxploitation movies use Black Panther-like groups as either window dressing (Superfly) or backup for the protagonist (Shaft or Foxy Brown)--or they are ignored altogether. In Spook, the Black revolutionary movement is one of the main characters.

The main character is Dan Freeman, played by Lawrence Cook. He is the first Black hired by the CIA under an affirmative action program. Greenlee drew heavily on his own history as one of the first Blacks in the USIA. "My experiences were identical to those of Freeman in the CIA," Mr. Greenlee told the Washington Post in 1973. "Everything in that book is an actual quote. If it wasn't said to me, I overheard it."

The name of the movie is a clever play on words and on racist practices in America. It was common practice in the '70s for businesses and government agencies to hire one or two Blacks, and place them in desks by the door in order to be visible. Of course, Freeman is doubly a "spook"--both a Black man and a spy, but a spy for the Black revolutionary movement within the CIA.

The talented Freeman is passed over for a position and promotion--instead, he is relegated to a copy room in the basement of CIA headquarters.

After leaving the agency and taking a job as a social worker on the South Side of Chicago, he quickly uses his CIA training to organize Black gangs into a network of underground guerrilla cells. When police murder a Black man, instead of rioting, the Black community becomes a highly organized military resistance movement, conducting hit-and-run raids, sabotage and assassinations.

The anger and outrage at racist America comes through loud and clear. Although blaxploitation movies had Black casts by definition, the vast majority were funded, produced and directed by white men. Importantly, Spook was funded mostly by the Black community, produced by Greenlee and directed by Ivan Dixon.

The movie also works against established characterizations about the Black community.

In one of the most memorable scenes in the film, a group of light-skinned freedom fighters are chosen for a special operation. One of them, "Pretty Willie" (played by an actual Black Panther), can easily pass for white and is still torn between Black and white worlds, but opts for Black. "I am not passing," he says. "I am Black, do you hear me, man? Do you understand?...I was born Black, I live Black and I'm going to die, probably because I'm Black."

Instead of being destroyed by this contradiction--in the tradition of the so-called "tragic mulatto"--this becomes one of the strengths of the freedom fighters. For example, light-skinned Blacks perform a bank robbery, but are able to later evade capture when they switch to white "costumes."

In many ways, The Spook Who Sat By the Door is a flawed movie. It was clearly made on a shoestring budget, and many of the scenes don't come together. There are also some political shortcomings. The project of revolution is a simplified Maoist scheme: organize Black gangs, get weapons, attack the police and military.

Although the movie spends a lot of time on the mechanics of building a paramilitary group, the end goal is noticeably absent. The closest it gets is in an exchange between Freeman and one of his lieutenants, Willie:

Willie: You know I can't figure you, man.

Freeman: What's to figure?

Willie: What are you in this for? You want, uh...power? You want revenge? What is it?

Freeman: It's simple, Willie. I just want to be free. What about you?

Willie: So do I, man. And I hate white folks.

Freeman: Hate white folks? This is not about hate white folks. This is about loving freedom enough to die or kill for it if necessary. Now, you are going to need more than hate to sustain you when this thing begins. Now, if you feel that way, you're no good to us, and you're no good to yourself.

SPOOK RAN in a few theaters around the country for about three weeks before it was shut down. The movie premiered at the Woods Theater in Chicago, where it was the second highest-grossing film. But according to Sam Greenlee:

The owner of the theater got a call from City Hall saying if he didn't take that film out of there--he owned six theaters--they were going to investigate all of his theaters, and he might lose his license. So he took a scene out of the film--the scene where we blow up the mayor's office. I went down there and told him, "Man, if you don't put that scene back in there, I'm coming down there with the Blackstone Rangers and take that film..." He put it back in.

Greenlee has always maintained that the FBI moved to shut down showings of the movie. For years, the movie was very difficult to obtain outside of bootlegs available directly from Greenlee himself. It was reissued in 2004 from a print that the director had hidden under a false name.

The commercial failure of Spook was devastating to Greenlee. Although he went on to write Baghdad Blues and a collection of poetry, like many talented Black radicals, his work never broke through to a larger audience.

The Spook Who Sat By the Door is an amazing movie, and nothing else quite like it has been produced. Although it was limited by its lack of resources, it deserves to be considered with the works of Bruno Pontecorvo, Costa-Gavras and John Sayles. Greenlee and The Spook Who Sat By the Door should be remembered alongside them.