Israeli denial and the Nakba

Lia Tarachansky is an anti-Zionist Israeli filmmaker, currently living in Ottawa, Canada, and a correspondent for The Real News Network. Her first feature documentary, On the Side of the Road, looks at the collective denial when it comes to what she considers the biggest taboo in Israeli society's social and historical memory: the Nakba, or "Catastrophe," as Palestinians call the war of ethnic cleansing that led to the foundation of Israel in 1948.

Ahead of her upcoming tour of film showings across the U.S., Tarachansky spoke with about the movie and her own journey out of Zionism. A shorter version of this interview was previously published at Electronic Intifada.

WHAT LED you to make On the Side of the Road?

I THINK it was discovering 1948 for myself and discovering just how little I knew of my own history. That was really revolutionary for me, and I thought that if it was so revolutionary for me, maybe it would also be for others.

HOW DID you first hear about the hidden history of 1948?

I WAS working as a journalist in Washington, D.C., and I was already pretty aware of the occupation and things associated with the occupation because I had met some anti-Zionist Jews for the first time back when I was in university [in Canada]. They opened my eyes to a lot of the things that I didn't know. It was a very long process of de-Zionization and facing up to some of the horrible things that our country and the Zionist movement have done.

Then, when I was working as a journalist in D.C., someone sent me a link to a video of a woman who was a veteran of the fighting in 1948. Her name is Tikva Honig-Parnass, and she ended up being in my film.

In that clip, she talks about massive ethnic cleansing campaigns that she was involved in. Up to that point, I had always thought that if the occupation were to end, then everything would be fine. If we just pulled back the troops and maybe took out the settlements, maybe did a land exchange or whatever, then everything would be fine.

All of a sudden, I was hearing about these ethnic cleansing campaigns, and that was really shocking. So I picked up a book by Ilan Pappe called The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, and that was it for me. That made it very clear to me that [the occupation of Palestine and all it entails] is not just about any one or another fact on the ground. This is about a mentality and an ideology. And in a way, that makes it a lot harder to tackle because it is a lot more amorphous, but at the same time, it makes it a lot easier to resolve the conflict because it is a conflict of ideas.

Zionism as an ideology argues that ethnocracy is a legitimate form for a state--that it's legitimate to have a state for only one group of people and to exclude the population that is indigenous to the land. That's a really terrible idea. In the 21st century, I really hope that we will be able to reconstruct the Israeli government and the Israeli state into a democracy.

YOU WERE raised in a settlement, and now you are anti-Zionist. Can you describe your own process of transformation? Was there a first instance that nudged you to begin your own process of de-Zionization?

THE STRONGEST thing for me was meeting a Palestinian for the first time and having a conversation with a Palestinian for the first time. That was after I was already in Canada, when I was in university. I was standing somewhere at the university, and this guy comes up to me and asks me for directions. We started talking, and he says, "You have a strong accent, where are you from?" and I say, "Oh, I'm an Israeli." And he says in a friendly manner, "Oh yeah? I'm a Palestinian!" So he asks for directions, and then he goes on his way.

And as he walks away, I realize that I'm holding my purse just a little bit tighter, that my whole body is kind of uptight, and it takes me a couple minutes to calm down from being terrified for my life. But then out of that brief interaction, I realized: Okay, he knows I'm an Israeli, he told me he's a Palestinian, and he didn't try to kill me.

That was revolutionary for me because, of course, I was told my whole life that Palestinians are just brainless, emotional, primitive, murdering anti-Semites who just want to kill Jews all the time. And here was this totally polite, sensible, nice guy, and he was a Palestinian.

I know it sounds horrible, but that, for me, was something that didn't fit with anything I had known before. And so it actually began a very violent process of tackling a lot of the mythology that I thought was true about the conflict.

Another very big part was played by anti-Zionist Jews at my university who opened my eyes--who insisted that I open my eyes to some of the things that I was blind to.

WHAT INSPIRED you to look at and understand the issue in terms of what you call "brainwashing" and "collective amnesia"?

I ACTUALLY started out making a very different film. I started making a film about historical truth, and I had all these historians and all these veterans, and they were going to prove, you know, journalistically, that this was collective punishment and ethnic cleansing, and that this was terrible.

I was shocked by some of the things that I was discovering: that people were sent in marches toward Jordan, and many people died on the way; that there were more than 30 massacres; that the state looted the property and land of refugees. The list of horrific things that happened in that war goes on and on and on.

But I found that when I was talking to people in Israel about some of these things, I wasn't seeing that "Oh my God!" look on their faces, you know? That's when I realized, "Okay, something's missing here."

Of course, that something is that my grandparents didn't fight in 1948. For me, I was actually discovering these things for the first time in my life. You know, obviously we don't learn this history in school, and no one in my family ever talked about 1948, because as Russian Soviet immigrants, we weren't [in Israel] in 1948. So what I realized was that I wasn't revealing the world to some people--some people already knew about it.

I ended up basing a lot of my film on the work of Stanley Cohen and his monumental book States of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering. In it, he talks about how societies look at their own collective historical taboos and the experience of their own collective amnesia.

What I found is that it wasn't that people didn't know [about the Nakba]. It was that they didn't assign a moral value to what they knew.

I wanted to understand why. Because I believed then and I believe now that Israelis by and large are an ethical people. But obviously they are involved in a brutal conflict. Many of us participate in that conflict. Many of us serve in the army and kill. But that's not because we are a genocidal people. I wanted to understand what was blocking people from seeing the truth, from understanding what they knew.

For instance, as an Israeli, you know that 1948 wasn't a "Pure Good War," but you don't want to know what it actually was--and anyone who tells you what it actually was is a self-hating Jew, and you should attack them, and so forth. This is exactly what Stanley Cohen calls "denial": this process of knowing and not knowing at the same time.

I eventually realized that this is what I needed to explore--this refusal to hear the truth, this refusal to hear the details. And why. Why are some people able to hear the truth and others not? Was there something about some people that makes them more able to hear the truth?

That was fascinating to me, and I thought it was also imperative to understand for those of us who hope to change things in Israel-Palestine for the better. So this is how I started working on On the Side of the Road.

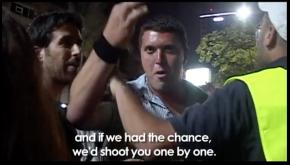

IN THE film, you show a lot of footage of what I think you could call Jewish extremists, rallying and saying things like, "Yes, I am a racist. I don't want Arabs here, and I don't want you here, either." Do you think Israeli society has always been like this? Or do you think this degree of open racism has developed over time?

I THINK that it's gotten way worse. This [latest war on Gaza] really brought a lot of the fascists out of the closet. But to be honest with you, I think that a lot of the street enforcers--and by street enforcers, I mean the ordinary people who are out on the street, for example, chanting these racist slogans--are just the ugly, in-your-face version of the whole ideology.

If you look at Zionism honestly--and I'm not talking about spiritual Zionism where you believe that Jews have a right to Zion and all that, I'm talking about nationalist Zionism, Zionism as practiced not even by Herzl, but by people like Ben Gurion--they argue that Israel is a state for the Jews, only for the Jews, and therefore necessarily excludes anyone who's not a Jew. Israel's Basic Laws, which are like the constitution, enshrine this principle.

So what do you do at what has been a crossroads of human mobility for millennia? People have been moving and settling and resettling, and empires have come and gone. How do you come to a place that is a crossroads and say, "No more. From now on, only one kind of people can move here, and everyone else is not welcome"? This is what has happened to the Palestinians, and it's what's happening right now to the refugees, and you can argue it's what happened to the Charkesi (Circassian) and the Mennonites and so on.

So I think that the street enforcers are just a natural product of that idea reaching its logical peak.

DO YOU see any hope for this racist ideology to be challenged?

I THINK that there is starting to be some debate [within Israel] about what it means to be a Jewish state, which was sparked actually by African refugees coming to Israel. Many arrived in 2006, and they didn't have any conflict with the Israelis or Jews, and yet they were treated as horribly as the Palestinians are treated. Most of them were deported; some of them were tortured and killed.

And so it raised questions in Israeli society, "Well, why are we doing this?" And of course the answer is that this is a Jewish state--only for Jews--so there's no space for anyone that's not a Jew.

I also think that the work of international activists has helped to bring to the surface this discussion of what a Jewish state actually means. That, I think, is new.

HOW DO you see the process of dehumanization of the Palestinians as a part of the Zionist project? For instance, how is the dehumanization of Palestinians learned or passed on growing up in Israel?

I WAS never told by anyone that we have to kick out the Palestinians. In fact, the first time I heard the word "Palestinian" was in Canada--in Israel, we call them "Arabs." So they don't have any national identity in our collective discourse about them.

But I think the brainwashing about Palestinians for Israelis is more about what is not said than what is said. I never thought about the Palestinians. They never played any major role in my life. As a settler, I never interacted with them. I never spoke to them. There was no place where our paths crossed.

Even though at that time when I was growing up in the settlement there wasn't the total segregation that you have today, still Israelis didn't and don't interact with Palestinians in any kind of meaningful way. Yet by the time I finished [high] school, I was completely convinced that it would be so much better if the Palestinians just were not here.

But how did I get there? Nobody told me that we have to kick out the Palestinians. It was just a natural thing that they are the cause of death to Israelis, they are violent, they throw stones at our soldiers, they started the intifadas, they want to kill all the Jews. So of course I'm fighting them. These are a people that we've been fighting forever and ever, and it's never going to end until either they're all dead or they're somewhere else. And that's it.

I never saw them. I never interacted with them. I never even physically heard the call to prayer that happens outside the settlement fence five times a day. I have no memory of it. The first time I actually remember hearing it is when I came back to the settlement already as an anti-Zionist.

So that just goes to show how dehumanized they were in my mind--that I didn't have any physical memory of them whatsoever.

WHAT DO you see as a potential solution in the region? And what do you think it would take to get there?

I TRULY believe that the vast majority of people want this thing to end. But as long as the U.S. and other global powers are involved in this project, nothing is going to change.

So I think that the very first step towards getting to a resolution is to stop funding the Israeli arms industry to use the Palestinians as a lab for its corporate gain. And this means sanctions. It means boycott. It means divestment. It means pressuring the U.S. and Israel and delegitimizing the idea of an ethnocracy. I'm not saying delegitimize the right of the Jewish people to live in Palestine or in Israel--I'm talking about delegitimizing Zionism.

WHAT AFFECT have you observed the film having on audiences?

I'VE FOUND that everyone I talk to has a strong reaction to the film.

For some people, it brings up things in them, and they come to question what they believe. In my further conversations with those people--and I encourage people to write me and to continue those conversations after seeing the film--what I gather is that the film triggers something in them that makes them question a lot of what they knew, whether they are activists or whether they were uninvolved and this is the first thing that they're seeing.

I think it connects to people's own personal denial. I think it helps them understand Israeli society, and for a lot of people it's a very disturbing film.

For example, my family and friends and the friends of my family--people who have been in my circle for many years, who are all very Zionist, hardcore rightwing Zionists--for them, it's a very disturbing film because I don't say anything in the film that's not correct, and yet it's things that they didn't think about, that they didn't hear before, and they know me so they know I'm not some crazy self-hating Jew, so they can't just not listen.

And the film says what it says in a very non-aggressive way, so I feel that a lot of people don't know how to shut it down, don't know how to shut it up. And that on its own, I think, is a success for the film.

WHAT WAS your goal in making the film, and what do you hope will come out of it?

I HOPE that people will see how difficult it is to tackle [the issue]...For example, when I was doing my journalism, a lot of times when I would do talks, people would come up to me and say, "But I don't understand how Israelis can do these things." And so my hope is that this film can help to explain that.

I also hope that the discussion in the activist community and around it shifts from focusing exclusively on how many checkpoints there are and how many settlements there are and away from this whole discourse about the facts on the ground. These are important, but really not as important as people think.

There's really nothing that exists right now on the ground that cannot be dismantled, you know? The settlements take up a very small part of the West Bank. The wall as a concrete wall takes up very little space.

By changing the ideology of the regime, everything is easily changeable. I think this is what we need to talk about, and this is what we need to tackle, and this is what I tried to do in my film. This is what I hope people will do when they screen it and when they talk about 1948.

CAN YOU tell me about the next project you're working on?

I JUST finished production on a film with journalist and filmmaker Jesse Freeston, who is also a very good friend of mine. It's for the Latin American TV network TeleSUR, and it's about ethnocracy and the African refugees. The film looks at why Israel, unlike any other developed state, doesn't have any process for refugees to get asylum-seeker status.

We look at what is specific about Israeli society, about this concept of ethnocracy, how it works, and how it has played itself out on this population of people who came to Israel seeking asylum as they do in other places, running away from wars and dictatorships, some of which Israel has even supported with weapons. Why were they faced with a wall and deportation and giant concentration camps and everything that Israel essentially did to try get rid of them?

It will come out in Spanish first on TeleSUR, and after that, we will make an English version.

First published in a shorter version at Electronic Intifada.