A lifetime fighting from below

pays tribute to New Politics co-editor and contributor Betty Reid Mandell, in an article written on behalf of the editorial board for the left journal.

THE EDITORIAL board of New Politics is saddened by the loss of one of our own: Betty Reid Mandell, who, with her husband Marvin Mandell, served as one of the journal's co-editors for most of the past decade.

Betty was also one of our most popular writers. Her articles from the magazine and her commentaries posted to the New Politics website have been the pieces we're most often asked for permission to reprint. (Most often by a large margin, according to those who handle the requests.) Readers seem to have picked up on Betty's genuine commitment to not just the rights, but the dignity of the poorest and most disenfranchised people in this, the wealthiest society in the history of the planet.

It was just two issues ago that we thanked Marvin and Betty for their years of service to New Politics. The only people who know enough to write a proper account of Betty's life are members of her family, who have enough to bear for now. But some kind of tribute is in order.

Here, then, are a few notes that may be of interest to New Politics readers--many of whom will join us in offering condolences to Marvin, and to their daughters, Christine and Charlotte.

BETTY REID was born in Denver, Colorado, on November 4, 1924. "I like to think that keeping my mother from voting for Coolidge was my first political act," she wrote not long ago, adding that it was "as effective as most of my subsequent political acts." (This and most other quotations here are taken from a manuscript of personal recollections she prepared for her family, who have graciously shared it.)

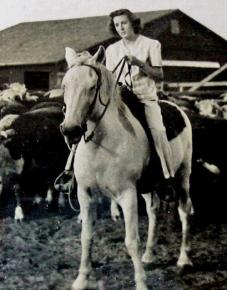

The youngest of four children, Betty grew up in Roggen, a town with a two-digit population about 50 miles northeast of Denver. Her father farmed a small tract of land acquired under the Homestead Act. It was not an especially fertile plot, and the threat of financial ruin would have been in the air even without the ecological catastrophe of the Dust Bowl.

Betty's mother was a loyal and active Republican, and the source of her earliest political memories, including visits to their home by GOP candidates. "Although my mother opposed Roosevelt and said any improvements he made were actually due to Herbert Hoover," Betty recalled, "she nevertheless was thrilled over the New Deal program of the Tennessee Valley Authority, and my father participated in the New Deal program of the 'ever normal granary,' which involved not planting wheat but letting land go fallow on alternate years." When Betty had to write a composition for school expressing excitement at finally having electrical lighting, her mother helped: "In fact, I suspect that my mother wrote most of the essay."

Woven into Betty's childhood memories--along with the chickens she helped raise and the sounds of coyote howls and train whistles she sometimes heard before falling asleep--were traces of agrarian radicalism and Progressive-era reformism still lingering in the 1920s and 1930s. Among these were her mother's membership in the Women's Christian Temperance Union, a group now much maligned, but one with a strong labor and feminist aspect in its heyday, and aligned with the Knights of Labor. There was also the Grange Hall. Like the church, it was one of the town's social centers (with the important difference being that dances were held there) but it also embodied the solidarity of farmers against the power of the railroads and other middlemen.

While writing her memories, Betty did some Googling and learned that Grange members "had been active in establishing rural free delivery of mail, the county extension service, and cooperatives. They were also active in women's liberation. Susan B. Anthony delivered one of her speeches in a Grange Hall. Roggen had two cooperatives--the gas station and the grain elevator. I wonder if the Grange Hall was instrumental in that, or was it the influence of the Farmer-Labor Party?"

These details seem meaningful with the advantage of considerable hindsight. But they don't add up to a destiny, no matter how you reckon them. At least as pertinent to Betty's future course was another side of American life expressed at the Grange Hall: "The Cooper boys stood on the sidelines, never daring to ask any white girl to dance. Jim Cooper was handsome and I wished I could dance with him, but understood the unspoken taboo against Black men dancing with white women."

Her anti-racist streak seems to have been nurtured by a Methodist youth group at college. Conscientious objectors from a nearby camp where they were interned sometimes attended meetings. Betty read in the group's national magazine about the forced relocation and detention of Japanese Americans, which she denounced in a speech at the local Rotary club. Betty had entered Colorado State College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts at Fort Collins in 1940, at the age of 16, meaning that her protest occurred while the internments were still underway. It would have been a courageous act anywhere in the United States at the time, much less in front of the Rotary club. And when the atom bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, she understood it as an atrocity. Her rebellion against Roggen norms may have taken no bolder form than registering as a Democrat, but she was on the way to something more radical.

BY HER own account, Betty learned about Marxist theory in the mid-1950s, after falling in love with Marvin, whose gregarious manner and years in the Workers Party and Independent Socialist League undoubtedly made him the ideal tutor. But a decade passed between finishing her undergraduate studies at Colorado State and meeting him in New York City. In retrospect, her twenties look like a time of steady movement from being "religious in a diffuse and unfocused way" (she says she prayed without feeling, not "very convinced that it did any good or that anyone was listening to me") to commitment to the very worldly challenges of social work.

That was to be her profession, both as practitioner and college professor, and something of the scale of her contribution to it is obvious even to a layperson. An Introduction to Human Services, a textbook she co-authored, is now in its eighth edition, while Survival News, the newsletter she helped start in 1986, continues to report on and contribute to the struggles of low-income women. One of her colleagues really ought to make a project of collecting tales of her work in the trenches of social work--not just as advocate for the poor but as someone who worked with people in need, helping them fight their way through bureaucratic obstacles built into the systems that are supposed to help them.

Betty Reid Mandell approached social work not as a liberal (hoping to make an easily distracted democracy live up to its claims of decency) but as someone who could--and did--cite Hal Draper's essay on "socialism from below" as a statement of basic orientation. In a two-part essay published by the journal Social Work in 1971, she characterized the evasive, invasive, humiliating and arbitrary practices of the existing welfare system in provocative terms:

Mechanization and depersonalization of life have become pervasive social problems. As Arendt says: "Political, social, and economic events everywhere are in a silent conspiracy with totalitarian instruments devised for making men superfluous." If we can help welfare recipients find a sense of community together, we will be working toward a society in which people care about what happens to each other.

Fuzzy communitarianism was not the solution she had in mind, as her next sentence makes clear: "History teaches us that democratic power is not given to the dispossessed; it is achieved through their own struggle." Here the influence of "The Two Souls of Socialism" seems quite clear. (Probably that of Marvin as well, though only Draper is cited in the footnotes.)

"Looking back over my history of wearing political buttons," Betty writes in her memoir, "is an interesting way to view my political education. In 1936 I wore a sunflower button for [Republican presidential candidate] Alf Landon. In 1952 I wore a button for Adlai Stevenson. In the 1960s, I wore a peace button against the Vietnam War. I don't remember how we got it, but Marvin and I owned a black anarchist flag with the anarchist A on it. In 2011, I wore an Occupy Boston button."

Betty once quoted a passage from Hannah Arendt that might serve to sum up the perspective that took shape across the 70 years of her steady movement leftward: "[E]quality, in contrast to all that is involved in mere existence, is not given us, but is the result of human organization insofar as it is guided by the principle of justice. We are not born equal; we become equal as members of a group on the strength of our decision to guarantee ourselves mutually equal rights."

For Betty this seems to have been not a doctrine but a pledge. Like Marvin, she was in it for the long haul. They devoted most of their eighties to New Politics--in solidarity with its aims, of course, but also in tribute to their longtime friends, the late Phyllis and Julius Jacobson, who founded the magazine. Only someone who has been trapped in a room with the editorial board of a socialist journal can imagine what Marvin and Betty put themselves through by taking the helm. We will always be grateful to them for it, and hope the generation that took its first political steps during Occupy will learn to see in her an inspiration and a standard of the commitment to expect from themselves.

First published at New Politics.