Tortured to death in New York City

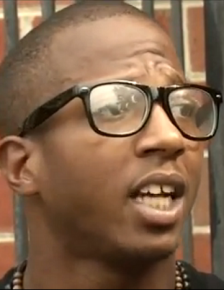

reports on the suicide of 22-year-old Kalief Browder, who faced three years of torture behind bars without a trial--and then courageously spoke out about his trauma.

BETWEEN MAY 2010 and June 2013, Kalief Browder was held without trial--that's right, without trial--in one of the country's most notoriously inhumane prisons: Rikers Island in New York City.

Due in large part to the reporting of Jennifer Gonnerman for The New Yorker in 2014, Browder's disturbing case gained uncommon recognition among celebrities and public officials. Two months ago, Mayor Bill de Blasio himself invoked Browder when motivating his reforms for the Rikers Island facility to the press.

For Browder, the traumatic horrors of Rikers Island continued to linger on long after his release. Despite heroic efforts to put himself through college and raise awareness of the plight of prisoners still in jail, Browder struggled with thoughts of suicide, surviving one failed attempt in November 2013.

On June 7, Gonnerman published another article announcing that Kalief Browder had indeed taken his own life the night before, ending a protracted battle to overcome the demons of his past.

ONLY DAYS before his 17th birthday five years ago, Browder was stopped by the NYPD in the Bronx's Little Italy. As he related to Gonnerman for her 2014 article, the officers surrounding Browder claimed he had been accused of stealing a backpack from a pedestrian--and then clumsily altered their story each time Browder explained his innocence.

After assuring Browder that he would most likely spend no more than a few hours in custody, the cops whisked him away, sending him on a bus to Rikers Island the next morning. Unable to make the $10,000 in bail asked of him and his family, Browder suddenly found himself trapped behind bars, with no timetable for his release.

Due to chronic backlogs and general malfeasance among city bureaucrats, Browder's trial was postponed, time and time again. Meanwhile, he struggled to endure incessant abuse committed by Rikers officers, and hostility between inmates stretched to the limits of their mental and physical health. Browder encouraged Gonnerman to try to acquire security footage of two beatings, which was published online in April 2015.

After more than a year in prison, Browder's prosecutor offered him a plea bargain: He could either profess his guilt and accept a three-and-a-half-year sentence or choose to contest the indictment, risking up to 15 years in jail if the trial didn't go his way. He elected to keep up the fight and prove his innocence.

But the worst was yet to come. Soon, Browder was forced into solitary confinement, where he was to spend more than two years before his eventual release. He made every possible effort to cope with these torturous conditions. But he recounted in an interview with the Huffington Post's Marc Lamont Hill, Browder made it through "five to six" attempts at suicide in his isolated cell. In a sickening display of cruelty, corrections officers greeted these attempts by severely beating him to the brink of unconsciousness, and then starving him of food for a full day.

It is a testament to Browder's conviction that, in the midst of all of this terror, he never wavered in demanding justice from the court system.

As the 33rd month of his incarceration without trial began, Browder was offered a second and even more attractive plea bargain. This time, his sentence would be time served. All he needed to do to escape his predicament now was accept a guilty plea. Yet Browder still refused to give in. As he told Lamont Hill:

I felt like I was done wrong. I felt like something needed to be done about this. I felt like something needed to be said. If I just cop out and say that I did it, nothing's going to be done about it. I didn't do it. Then no justice is served. I felt like I had to fight.

Weeks later, a city judge dismissed all charges against Browder as insubstantial, clearing him to leave Rikers Island behind for good. But the inner torment that had haunted Browder in jail continued to plague him after his departure. "In my mind right now," he told Gonnerman, "I feel like I'm still in jail, because I'm still feeling the side effects from what happened in there."

Two years passed, in which Browder applied himself to the tasks of recuperation. In the end, however, the traumas accumulated in New York's terror chambers claimed Browder's life.

THE LAST thing Kalief Browder wished to discuss after his release was what he had been through on Rikers Island. But his principled opposition to injustice led him to speak out when given the opportunity.

"The whole point of being on this show is to get my story out there", he told Lamont Hill, "because this happens every day and I feel like it's got to stop...when they get offers [plea bargains], a lot of people aren't as strong. They will take the plea deal knowing that they didn't do it--and it happens every day".

Browder was not exaggerating. At the unveiling of de Blasio's "Justice Reboot," a plan to reform Rikers Island, the mayor and his new Corrections Commissioner Joseph Ponte admitted that there were 1,500 prisoners at the Rikers facility who had gone more than a year without trial.

This announcement accompanied a sweeping report by the U.S. Department of Justice, which chronicles the abusive conditions at the island prison. The Jails Action Coalition (JAC), which has publicized and resisted the terrors of NYC prisons for many years, places the total number of inmates in the city incarcerated without trial even higher:

Over 12,000 New Yorkers are incarcerated on Rikers Island and in other city jails each day. Over 9,700 of those incarcerated each day are pre-trial detainees who are being held without being convicted of a crime. Most are there because they cannot afford bail.

In other words, although Browder's incarceration without trial was exceptionally long, his story is by no means a rarity. Many of these individuals are understandably persuaded to accept the perverse plea bargains that the state proposes, often admitting to crimes they did not commit.

JAC's figures suggest a broader pattern of oppression at work in New York City. The root cause of Browder's struggle, and of thousands of others like it, is the intensive policing and imprisonment of residents from working-class neighborhoods in the five boroughs.

The function of the police is not to keep these neighborhoods safe and secure, as state officials lead us (and often themselves) to believe. Their true function is to contain and control impoverished communities so that city government can allocate the bulk of its resources to aid the real estate sector's profiteering schemes, while in large part ignoring the needs of everyone else.

IN THE wake of the emerging Black Lives Matter movement, de Blasio's "Justice Reboot" plan proposes a series of reforms on Rikers Island, including a ban on solitary confinement for youths under the age of 18 and a 25 percent decrease in the prison population by 2025.

Even if these measures are implemented, they do not nearly suffice to address the concerns raised by Browder's case. The idea that reserving solitary confinement for those 18 and above is somehow "progressive" reveals how low the bar has been set for criminal justice reform in today's United States, which locks up a higher percentage of its population behind bars than any other country.

Kalief Browder wished to see a world where neighborhoods were safe and secure and nobody was unjustly imprisoned. The bottom line is that these aspirations can only be realized if the police and prison system at large is dismantled, and the investments allotted to it rerouted towards full employment, health care, education and recreation, all democratically run by and accountable to the people.

In New York City alone, de Blasio's 2014-15 budget set out to spend $8.9 billion on the police department, compared to only $1.1 billion on the Administration of Children's Services (ACS) and $865 million on the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, according to the most recent Executive Budget Summary.

The necessary resources are there to be had to build a robust and accommodating social infrastructure for all. To honor Kalief Browder and the countless other victims of racism and exploitation, we must continue to build a formidable movement capable of reorganizing the very foundations of society. Browder's inspiring dedication to justice shows us what this movement must be made of.