Socialism according to Eugene V. Debs

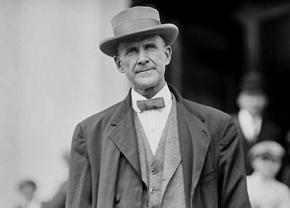

What did the man who Bernie Sanders today claims as his personal hero really stand for? tells the story of American socialism’s best-known figure.

IT’S NOT your typical presidential candidate who identifies as a socialist, but Bernie Sanders does. A poster of Eugene V. Debs, the popular Socialist Party leader of the early 20th century, hangs on his office wall as a tribute to Sanders’ self-proclaimed hero.

Like Debs, who ran for president five times, Sanders is also running for president. But that, my friends, is where the similarities end.

The socialism of Bernie Sanders—who says he’s running as a Democrat to shift the debate to the left--is fundamentally different from that of Eugene Debs, who committed his life to spreading the ideas of revolutionary socialism. Sanders is promoting something that falls far, far short of the fundamental change that Debs fought for. Sanders relegates socialism to the realm of nice ideas that can be talked about, but never really be implemented—while he accepts what little the Democratic Party is willing to concede.

For Sanders, the working class is a “constituency,” a backdrop to the political campaigns he runs and the legislative work he does. For Debs, the working class was in the foreground of everything he hope to achieve—because he believed, as a convinced Marxist, that workers have to make the fundamental and lasting transformation that he called socialism.

The fact that the mainstream media has been forced to acknowledge the existence of Eugene V. Debs recently is a little victory, since his story is largely buried. In fact, Debs’ home in Terre Haute, Indiana, now the location of a modest museum, served as a fraternity house from 1948 to 1962. The brothers of Tau Sigma Alpha were probably too busy partying to think about the legacy of the town’s famous resident.

At best, Debs is treated like an anachronism—a relic of a bygone era and a reminder of the days of old-fashioned ideas like socialism. But the true legacy of Eugene V Debs speaks to America’s radical tradition during his own time and the potential popularity of socialist ideas today.

LIKE MOST socialists, Debs arrived at radical ideas out of his experiences of capitalism.

His life coincided with a huge transformation in U.S. society, and those events impacted the way he looked at the world. When Debs was 7 years old in 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. At the age of 14, he got a job painting signs for the railroad—a year later, in 1870, he became a railroad fireman. The same year, John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil, which would become the largest multinational corporation in the world.

When Debs was 21 in 1877, railroad workers across the country went on strike against poverty wages and dangerous working conditions. Nine years later, an explosion went off at a rally in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, the epicenter of the fight for the eight-hour day—and radicals and anarchists were framed for it, leading to the hanging of the Haymarket martyrs. Seven years later, Debs helped organize the first industrial union: the American Railway Union.

Debs came of age during the era of the robber barons, times of unbridled greed and capitalist expansion. The growth of the railroads meant that modern cites began to emerge across the country. During this time, the U.S. also experienced repeated economic depressions. The image of men riding the rails and looking for work was a familiar one.

Debs worked on the railroad for a few years—before he became an organizer for the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen—and he developed a deep understanding of the daily dangers faced by railroad workers. In 1893, he helped start the American Railway Union (ARU), which was inspired by the militant Western Federation of Miners founded the same year.

Debs was forever changed as a leader of the Pullman strike in Chicago in 1894 against the Pullman Sleeping Car Co. The federal government intervened against strikers, provoking violence that ended in the deaths of 13 workers. With this, Debs learned both the power of the working class when it used the strike weapon—and the lengths the federal government would go to side with the bosses against workers. As he wrote in 1902 in an article titled “How I became a socialist”:

The combined corporations were paralyzed and helpless. At this juncture there were delivered, from wholly unexpected quarters, a swift succession of blows that blinded me for an instant and then opened wide my eyes—and in the gleam of every bayonet and the flash of every rifle the class struggle was revealed. This was my first practical lesson in Socialism, though wholly unaware that it was called by that name.

An army of detectives, thugs and murderers were equipped with badge and beer and bludgeon and turned loose; old hulks of cars were fired; the alarm bells tolled; the people were terrified; the most startling rumors were set afloat; the press volleyed and thundered, and over all the wires sped the news that Chicago’s white throat was in the clutch of a red mob; injunctions flew thick and fast, arrests followed, and our office and headquarters, the heart of the strike, was sacked, torn out and nailed up by the “lawful’ authorities of the federal government; and when in company with my loyal comrades I found myself in Cook County jail at Chicago with the whole press screaming conspiracy, treason and murder, and by some fateful coincidence I was given the cell occupied just previous to his execution by the assassin of Mayor Carter Harrison Sr., overlooking the spot, a few feet distant, where anarchists were hanged a few years before, I had another exceedingly practical and impressive lesson in Socialism.

Later confrontations with the state and police convinced Debs of the violence of the government and the need for workers to organize their own self-defense. So by 1914, in response to the horrible brutality meted out on a tent colony of striking miners and their families in Ludlow, Colorado, Debs argued in an article in the International Socialist Review that the mineworkers’ unions should create a “Gunman’s Defense Fund.”

THESE EXPERIENCES also exposed to Debs the futility of relying on politicians to win better conditions for working people. Previously, Debs was a member of the Democratic Party—he campaigned for the Populist Democrat William Jennings Bryan in 1896. Workers needed their own organization, he concluded, and Debs devoted the rest of his life to building it.

He helped found the Socialist Party (SP) in 1901 and ran on the party ticket for president five times. In 1912, he won almost a million votes, good for about 6 percent of total. In 1920, he ran from prison where he was incarcerated for his opposition to the First World War, and won almost a million votes again. In 1908, he traveled across the country in a train dubbed the “Red Special,” speaking to thousands of people about socialism.

During his campaigns, Debs challenged the capitalist politicians and explained why they had nothing to offer workers. And he had advice for left-wing Democrats: If they really supported left-wing ideas, then they should defect and join the Socialists:

The radical and progressive elements of the former Democracy have been evicted and must seek other quarters. They were an unmitigated nuisance in the conservative counsels of the old party. They were for the “common people” and the trusts have no use for such a party.

Where but to the Socialist Party can these progressive people turn?…Every true democrat should thank Wall Street for driving them out of a party that is democratic in name only, and into one that is democratic in fact.

Above all, election campaigns for Debs were opportunities to create a platform for socialist ideas and make an argument that it was the working class, not politicians, that had the power to transform society. He made this point to fellow SP members in 1911:

We should seek only to register the actual vote of Socialism, no more no less. In our propaganda we should state our principles clearly, speak the truth fearlessly, seeking neither to flatter nor to offend, but only to convince those who should be with us and win them to our cause through an intelligent understanding of its mission…

Voting for Socialism is not Socialism any more than a menu is a meal. Socialism must be organized drilled, equipped and the place to begin is in the industries where the workers are employed…

Without such economic organization and the economic power with which it is clothed, and without the industrial co-operative training, discipline and efficiency which are its corollaries, the fruit of any political victories the workers may achieve will turn to ashes on their lips.

The electoral campaign was only a means to a greater cause, the self-organization of the working class. In this way, Debs agreed with the left wing of the Socialist Party—people like Bill Haywood and Mother Jones, who would help found the Industrial Workers of the World. They advocated workers taking control where the power of the ruling class was rooted—in the factories. But he disagreed with others on the left who argued that elections had no role to play at all. He thought the two things—election campaigns and workplace organizing—were both jobs for socialists.

REPEATEDLY, DEBS emphasized that socialism had to be achieved by workers themselves. In a 1905 speech, he argued:

Too long have the workers of the world waited for some Moses to lead them out of bondage. He has not come; he never will come. I would not lead you out if I could; for if you could be led out, you could be led back again. I would have you make up your minds that there is nothing that you cannot do for yourselves.

You do not need the capitalist. He could not exist an instant without you. You would just begin to live without him. You do everything and he has everything, and some of you imagine that if it were not for him you would have no work. As a matter of fact, he does not employ you at all; you employ him to take from you what you produce, and he faithfully sticks to this task.

If you can stand it, he can; and if you don’t change this relation, I am sure he won’t. You make the automobile, he rides in it. If it were not for you, he would walk; and if it were not for him, you would ride.

Within the SP, members had very different ideas about socialism and how it would be achieved. Some believed in socialism as a steady increase in social reforms achieved by socialists being elected to political office—others looked to a revolutionary transformation of society. As a result, conservative and backward ideas, like the racism of SP leader Victor Berger, existed alongside the revolutionary socialism of Debs.

Divisions grew between the SP left and right and came to the breaking point with the First World War and the successful workers’ revolution in Russia.

Debs proudly represented the internationalist position of genuine socialists. He opposed the imperialist war, in the face of the epidemic of patriotism that caught hold across the U.S. and the state repression faced by antiwar activists who dared to speak out.

Debs’ famous Canton speech in 1918—which was almost two hours long and dutifully transcribed by a federal government stenographer planted in the audience--remains necessary reading for socialists today. At the age of 63, he was sentenced to prison, based on the speech, which was submitted by the prosecution during Debs’ trial.

When news that Russian workers had taken power in 1917 reached the U.S., Debs celebrated the revolution. Like leftists around the world, he was inspired by the Russian workers’ example and gained confidence in the fight against war and for the self-emancipation of the working class.

Eventually, those leftists who remained in the SP quit to help form a new Communist Party on the model of what Lenin and the Bolsheviks had built in Russia. Debs, while he supported the Russian Revolution and remained a revolutionary, nonetheless stayed in the SP.

For his final presidential campaign in 1920, Debs ran as inmate #9653 from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. From jail, Debs learned more about the injustice system from his fellow prisoners. He became so beloved that when he was released, they presented him with a hand-carved cane depicting historic labor struggles.

In Walls and Bars, Debs outlined his unwavering vision of a socialist future:

Under Socialism no man will depend upon another for a job, or upon the self-interest or good will of another for a chance to earn bread for his wife and child. No man will work to make a profit for another, to enrich an idler, for the idler will no longer own the means of life. No man will be an economic dependent, and no man need feel the pinch of poverty that robs life of all joy and ends finally in the county house, the prison and potters’ field…

Industrial self-government, social democracy, will completely revolutionize the community life. For the first time in history the people will be truly free and rule themselves, and when this comes to pass poverty will vanish like mist before the sunrise. When poverty goes out of the world the prison will remain only as a monument to the ages before light dawned upon darkness and civilization came to mankind.