A flawed revolutionary icon

looks at the important lessons to be drawn from Samuel Farber's new book, The Politics of Che Guevara, in a review first published at the revolutionary socialism in the 21st century website.

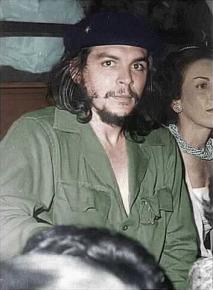

FOR TWO generations of activists, Ernesto Che Guevara has symbolized a kind of selfless heroism. His relative youth at his death in 1967 (he was 38) conserved his air of rebelliousness and the image of a man interested only in the struggle, rather than in power.

Yet Sam Farber who acknowledges these qualities, describes him early in his new book, The Politics of Che Guevara, as "irremediably undemocratic." The contradiction is striking and central to Farber's critical analysis of Che's life as a revolutionary.

Farber's starting point is the understanding of socialism as the self-emancipation of the working classes, with the emphasis on self. In other words, revolution is, as Marx says (in his Theses on Feuerbach) the "coincidence of the changing of self and the changing of circumstances." It is in acting collectively in the world that the majority come to recognize their own power and become subjects of history rather than merely its objects. That is the central idea of Marxism.

Yet Che Guevara's politics and his practice were based on a very different idea--that it is revolutionaries who make the revolution. And they do so irrespective of the circumstances in which they operate, because it is the will of the revolutionary vanguard that is the key.

This voluntarist view is not just misguided; it is alien to the revolutionary tradition to which Farber (and myself) belong. The substitution of the leaders for the mass movement, points ahead to a very different future prefigured in the guerrilla method.

Farber explains that Edward Bellamy's 19th century utopian novel Looking Backward was one of Guevara's inspirations. Interestingly the future state that Bellamy imagines was modeled on an army.

Farber reminds us that revolutions do not automatically lead either to dictatorship or democracy; their outcome will depend on the "leading politics" of the movement. In the case of Cuba after 1959, the state was shaped around the command model--a pyramid of orders delivered from above and accepted without question--in which democracy appeared as a risk to the authority of leadership.

IT SEEMS curious at first that someone with Guevara's background should have come not just to accept, but to vigorously advocate that inescapably Stalinist project--to dismiss the right to strike and the independent organization of workers as mere obstacles on the road to revolution and to scorn the "false prophets of mass democracy".

Born in Argentina to left wing parents influenced by the especially Stalinist Argentine communist party, Guevara grew up as a radical Bohemian, a life-style rebel who spurned what he saw as bourgeois habits, from cleanliness to ostentatious consumption. His protest against that culture took the form of a kind of a puritanical asceticism.

The politics would come later, though he was a visceral anti-imperialist from early on. And by the time he reached Mexico, where he met the Cuban rebels for the first time, he had begun to steep himself in Marxism. But it was a Marxism in the abstract, not linked to activism of any kind.

The members of the 26th July Movement with whom Che landed in Cuba in December 1956 to launch the guerrilla campaign were, as Farber describes them, rightly in my view, "déclassé"--political rebels from mainly middle class backgrounds with few roots in the mass movement. Guevara shared that dislocation.

With the victory of the revolution in January 1959, Che joined the Castro brothers in its leadership. It may surprise many readers that Che was--and Farber marshals a powerful body of evidence to prove his case--together with Raúl, the architect of the new state, though ultimately the political skills of Fidel carried him to the top of the pyramid.

It was not a search for personal power that made Che the unconditional supporter of a one-party state--unlike Fidel, for whom it was his driving impulse. But it reflected an admiration for the Stalinist state in its most sectarian and undemocratic manifestations--the state as the exclusive vanguard.

That model drove Che's critically important interventions in the economy in the early years, based on rapid industrialization, but taking no account of the realities of the Cuban economy. By 1962, Che acknowledged how mistaken those economic policies were, but by then it was too late to turn the clock back.

WHAT THIS "economic voluntarism", as Farber calls it, illustrated was not just the single-minded dedication to the immediate creation of a communist state along Stalinist lines, but also a central feature of Guevara's politics that Farber calls his "political tone-deafness" or his "schematism".

It was already implicit in his early (1960) manual on Guerrilla Warfare, and definitive especially in his later activities in the Congo and Bolivia. For Guevara, political strategy was not shaped by the specific circumstances in which it unfolded.

So in a Bolivia with an extraordinary tradition of working-class militancy, and which was in the throes of a bitter strike wave when he arrived in 1966, he was insistent on creating a rural guerrilla force and paid no attention to the working-class movement except to call on its militants to join the guerrillas (which no more than a handful did). A year later Che was dead, together with most of his comrades.

In the Congo the failure of the movement there was attributed by Guevara to the lack of a vanguard leadership. And in his arguments with the French agronomist Rene Dumont over the right to strike, Guevara angrily rejected Dumont's insistence that it was fundamental to a socialist democracy, just as he did in his famous essay Socialism and man in Cuba, insisting that "a mass party was only possible when the masses have attained vanguard consciousness".

By the mid-sixties Che was increasingly critical of the Soviet economy's drift towards capitalism, but at no point did that lead him to a criticism of the bureaucratic state. How could it, after all, when he had been an architect of the one-party state in Cuba?

What impresses in Farber's book is the way in which he interweaves a critical assessment of Guevara's politics with general arguments about the meaning of socialism. And at its heart, that socialism is democracy of the most radical and profound kind.

The one-party state that Che forged with Raúl Castro continues in Cuba today, overseeing the restoration of a capitalist economy. The lack of resistance to its inevitable effects are a product of a one-party regime that denied the diversity of working-class politics and imposed a system in which the majority had no freedom to act, criticize or generate alternative socialist projects.

Would Che have been happy with the outcome, and the corruption and manipulation of power it has produced? His role in creating the system suggests that he would, albeit perhaps with some misgivings. And he would have despised the yearning for a materially better life among the majority as the unacceptable infiltration of capitalist values.

So what should we do with this flawed revolutionary icon? Recognize that his high moral standards, his resolute internationalism, and his egalitarianism were qualities to cherish. But the one-party state he favored and its repression of democracy consigned the subjects of revolution to a position in which self-emancipation became impossible, as the self-proclaimed vanguard usurped their role, at first in the name of revolution but soon, and in the absence of any possibility of control from below, in their own self-interest.

First published at the revolutionary socialism in the 21st century website.