The ways John Berger saw

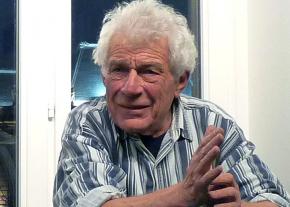

Artist , whose Morbid Symptoms exhibition opens this week at Portland's White Gallery, remembers the life of pioneering art critic and author John Berger.

JOHN BERGER--a giant of art writing, literature and Marxist cultural analysis who helped multiple generations grapple with and critically think about art, history, politics, and the act of looking--died on January 2 at the age of 90.

Berger was widely regarded as one of the most influential writers on art of the last 60 years. But he was much more than this, producing plays, screenplays, poems, novels, political and social essays, collections of drawings, and 33 works that fell into the category of "other."

All of his work was driven by a desire to see a more just world, and central themes included the importance of the past in addressing the present; the relation between art and beauty and imagination; and the importance of looking. The writer Susan Sontag described him as peerless in his ability to make "attentiveness to the sensual world" meet the "imperatives of conscience."

Berger identified himself as a Marxist and, above all, saw himself as a storyteller. "Unlike what most people think, storytelling does not begin with inventing, it begins with listening," Berger says in The Seasons in Quincy, a four-part film on his life. "If I'm a storyteller, it's because I listen."

BERGER WAS born in 1926 in Hackney, London, into a middle-class family. The child of a former infantry officer during the First World War, Berger was sent away to boarding school at the age of six and dropped out at 16, having spent most of his time there drawing and reading anarchist newspapers.

Berger joined the army at 18, but refused to become an officer--something expected of him because of his class background--and so remained in a recruiting unit just outside of Belfast. He later cited this as one of his early social-political influences, as it was the first time he had lived among working-class men. He similarly noted an experience where his father sent him to spend the day among coal miners when he was a boy.

Asked about his influences in a 1984 interview with Geoff Dyer in Marxism Today, Berger said:

[There are] two things that are so deeply inside me that they are hardly even at the level of informed ideas. One is a relation to what I have always felt to be the "mystery" of art. The other is a gut solidarity with those without power, with the underprivileged. Where perhaps I am a bad Marxist is that I have an aversion to political power, whatever its form. Intuitively, I am always with those who live under that power.

From the army, Berger went to the Chelsea School of Art, where he studied painting, but he pivoted to writing by the 1950s when he got a job as an art critic for the New Statesman. As he later said in an interview with the New Republic:

The reason I stopped painting at the end of the '40s was what was happening in the world: the threat, above all, the threat of nuclear war. This was before the Soviet Union had parity. This threat was so pressing that painting pictures--that somebody would go hang up on the wall--seemed...[dismissive hand gesture]. But to write, urgently, in the press, anywhere, everywhere, seemed so necessary.

During this time, Berger was also around the British Communist Party, occasionally writing for its paper, though he never joined as an official member. Yet throughout his life, Berger maintained that he was a proud Marxist.

"My reading of Marx... helped me enormously to understand history, and therefore to understand where we are in history," he told the BBC's Newsnight in 2011. "And therefore to understand what we have to envisage as a future, thinking about human dignity and justice."

BERGER IS perhaps best known for his 1972 four-part BBC series Ways of Seeing (and the book subsequently based on it).

Described by his adversaries in the field of art academia as the art student's equivalent of Mao's Little Red Book, the series made waves when it debuted, offending one side and inspiring the other. Today, the book has sold more than a million copies and remains a staple in British art school education.

In the opening sequence, Berger immediately established that his show was something different, using a box cutter to slice out the figure of Venus in a mocked-up painting of Botticelli's Venus and Mars, and removing it to discuss in isolation.

In the series, Berger drew on Marxist philosopher Walter Benjamin's ideas from the essay "Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" to question what it is we are told to think about classical art, and to examine how the meaning of images change as the material circumstances of the viewer change. As Ratik Asokan wrote in New Republic:

At a time when arts programming generally featured suited men pontificating before fireplaces in their vacation villas, Ways was filmed at an electric goods warehouse, and was anchored by the longhaired, Aztec-print-wearing, leftist intellectual John Berger, who addressed the camera in an equal and non-elitist tone...

At a time when critics only concerned themselves with "aesthetics," Berger set about revealing the capitalist and colonial ideologies behind much Western art, as well as putting forth a major feminist critique of it. Ways of Seeing was pioneering for the ease with which it moved between analyzing the highbrow (e.g., the great masters) and the lowbrow (e.g., advertisements), more importantly, for how it kicked down the supposed distinction between the two.

In the second episode of the series, Berger put forward a revolutionary feminist analysis of how women are seen that still resonates today. The episode begins: "Men dream. Women dream of being dreamt of. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at."

Berger deconstructed the classical "nude" in Western painting and compared this to modern images of porn and women in advertisements, as a way to begin a conversation about the place of women in society, both when the "classics" were painted and today. "You paint a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her," Berger says. "Put a mirror in her hand, and you call the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure."

Halfway through the episode, Berger asserts that it's illogical to only have male voices talking about these issues, and invites a group of women in to discuss the topic. The way he actively listens--encouraging discussion, valuing and really hearing what the different women put forward as their own ideas and interpretations of the art and how it impacts them--is beautiful in itself.

Previously, in the first episode, he similarly asked a group of young children what they thought about a Caravaggio painting, taking seriously what they say in a way most critics would never dream of. These moments of the series shed light on Berger's political statement about who art is for, but they also illuminate his love for humanity and deep anti-elitism.

To the uninitiated, this might not sound particularly groundbreaking. But as Emma Hope Allwood noted in Dazed magazine:

This was 1972--the Sex Discrimination Act was still three years away, contraception wasn't yet covered by the [National Health Service], and it would be almost a decade before women could take out loans in their own names without a male guarantor. And yet, here they were, on one of only three channels on mainstream television, sitting in a group and discussing issues such as agency, empowerment, and their relationships to their own bodies and to men.

The ending lines of the first and last episodes of the series also speak to Berger's larger philosophy throughout much of his work. He reminds the viewer to not only look, but to ask questions: "I hope you will consider what I arrange, but be skeptical of it. What I've shown, and what I've said...must be judged against your own experience."

THE SAME year that Ways of Seeing aired, Berger won the Man Booker Prize for his novel G. At the awards ceremony, he again put his politics into practice, provoking many when he announced that in protest against award namesake Booker McConnell's historic exploitation of indentured labor on the sugar plantations of what was then known as British Guiana, he would donate half his prize money to the British Black Panther Party--which he described as "the Black movement with the socialist and revolutionary perspective that I find myself most in agreement with in this country."

The other half of the money, he announced, would be put toward the writing of his next book, A Seventh Man, which would document the experiences of migrant workers across Europe.

In addition to A Seventh Man, Berger wrote novels about peasants (the trilogy Into their Labours); people living with AIDS (To the Wedding); and the homeless (King: A Street Story).

In each of these, Berger strove to "write equal to" those he was portraying, not to patronize them, and not to use them to simply serve a political purpose. He understood the situations of many of his subjects to be the result of "globalization and the new world economic order," but as he explained in an interview with the BBC's Meridian in 2001, when you write, people "have to be there for their own sake. Because they are real and because they are there living. Hoping. Desperate. Surviving."

As for his many essays, Berger often used art as a jumping-off point to talk about diverse topics ranging from the Zapatista movement in Mexico, to the legacy of Rosa Luxemburg, to Israel's massacres in Gaza.

In one example, published as a "Letter from John Berger to the Palestinian Resistance", Berger wrote:

Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5 summons up a happiness that is almost boundless and which, for that very reason, neither he nor we can possess. The Concerto was nicknamed the Emperor. It carries us to a horizon of happiness we cannot cross...

I send it today to the Palestinian students demonstrating at the Beth El checkpoint at the entrance to Ramallah. They too are inspired by a vision of happiness they cannot know in their lives. I send the Concerto as an arm to be used in their struggle against the Israelis who occupy and colonize their homeland. Beethoven approves. He cares deeply about politics. His Symphony No. 3, the Eroica, was inspired by Napoleon when he was still a freedom fighter and before he became a tyrant. Let's rename the Emperor for a day: Piano Concerto No. 5, the Intifada.

Berger came to identify deeply with this struggle in particular later in his life, visiting Palestine several times and publicly endorsing the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement.

ONE OF the aspects of John Berger's work that is so inspiring and motivating to me and, I think, to many artists and people who care deeply about art is how he not only put words, but in essence dedicated his life, to illustrating how and why art has the potential to matter significantly in the struggle for a better world. In Collected Essays, Berger writes:

Yet why should an artist's way of looking at the world have any meaning for us? Why does it give us pleasure? Because, I believe, it increases our awareness of our own potentiality. Not of course our awareness of our potentiality as artists ourselves. But a way of looking at the world implies a certain relationship with the world, and every relationship implies action. The kind of actions implied vary a great deal...

A work of art can, to some extent, increase an awareness of different potentialities in different people. The important point is that a valid work of art promises in some way or another the possibility of an increase, an improvement. Nor need the word be optimistic to achieve this; indeed, its subject may be tragic. For it is not the subject that makes the promise, it is the artist's way of viewing his subject. Goya's way of looking at a massacre amounts to the contention that we ought to be able to do without massacres.

As Robert Minto wrote in the LA Review of Books, "For John Berger, art criticism is a revolutionary practice. It prepares the ground for a new society."

Remaining rooted in a materialist and sober assessment of the way things are, Berger maintained the greater need to create a new reality and reminded his audience of the continual need for inspiration and hope--and thus the need for the production of these things--in order for us to fight for that new reality.

BERGER'S INSIGHT into the question of how we act to create a new "potentiality" can be seen in his essay "The Nature of Mass Demonstrations." Originally published in New Society in May 1968, Berger begins by noting that it is made up of conclusions he had come to while studying certain aspects of a mass demonstration in Milan in 1898 for a story he was writing, "which may perhaps be more widely applicable."

This essay should be critical reading as we gear up to protest Trump's inauguration and to rebuild a protest movement in the wake of everything that might be in store under the president-elect, for we will surely come up, again and again, against the question of "why protests matter":

The truth is that mass demonstrations are rehearsals for revolution: not strategic or even tactical ones, but rehearsals of revolutionary awareness. The delay between the rehearsals and the real performance may be very long: their quality--the intensity of rehearsed awareness--may, on different occasions, vary considerably: but any demonstration which lacks this element of rehearsal is better described as an officially encouraged public spectacle...

A demonstration, however much spontaneity it may contain, is a created event which arbitrarily separates itself from ordinary life. Its value is the result of its artificiality, for therein lies its prophetic, rehearsing possibilities.

By demonstrating, [protesters] manifest a greater freedom and independence--a greater creativity, even though the product is only symbolic--than they can ever achieve individually or collectively when pursuing their regular lives. In their regular pursuits they only modify circumstances; by demonstrating they symbolically oppose their very existence to circumstances...

This creativity may be desperate in origin, and the price to be paid for it high, but it temporarily changes their outlook. They become corporately aware that it is they or those whom they represent who have built the city and who maintain it. They see it through different eyes. They see it as their product, confirming their potential instead of reducing it.

Lastly, it only seems fitting to touch on Berger's thoughts about the dead. In several interviews, Berger mentioned his firm belief that "the dead are among us," in the sense of past struggles for liberation serving as a building block for a new generation. As he told the New Statesman:

The past is very present to me and has been for a very long time...What I'm talking about...is a very ancient part of human awareness. It may even be what defines the human--although it [was] largely forgotten in the second half of the 20th century. The dead are not abandoned. They are kept near physically. They are a presence. What you think you're looking at on that long road to the past is actually beside you where you stand.

As we move ahead into a world without John Berger, armed with his way of seeing and so much of his writing, he will, in many ways, continue to be beside us where we stand.