When workers shut down Kansas City

One hundred years ago this week, workers in Kansas City organized a general strike, showing the strength of solidarity across race and gender, writes

ON THE morning of March 27, 1918, a weeklong general strike began in Kansas City, Missouri. About 25,000 workers participated in the sympathy strike, called in solidarity with commercial laundry workers--mostly low-wage women, Black and white.

While the history of the Kansas City General Strike isn't widely known, this struggle stands in a tradition of fierce labor battles in the U.S., including the Seattle General Strike of 1919 and the Minneapolis Teamster Rebellion in 1934.

The Kansas City general strike occurred at a time when few women were union members outside the textile and shoe industries. The only other general strike in U.S. history that was sparked by a walkout by women workers was in Oakland in 1946.

The effects of wartime conditions on workers contributed to the strike's amazing militancy and solidarity--while at the same time, the government's appeal for workers to support the war effort also limited the radical potential of a general strike.

IN DECEMBER 1917, male laundry delivery drivers in Kansas City requested a raise and union recognition. When the owners denied the drivers' requests in January, workers responded with a strike in February 1918. Women workers immediately joined the male drivers, and both groups vowed to stay on strike until they all had their demands for pay and union recognition met.

Women laundry workers received very low pay. They worked in extreme heat with chemical fumes, and fainting was a regular occurrence.

The laundry owners quickly offered the women strikers a raise without union recognition, and blamed the higher-paid drivers for tricking the supposedly happy women into striking.

As the laundries returned to regular business with scab labor, small groups of men and women strikers began attacking laundry wagons in early March. When a driver took a bundle of laundry to a house, several strikers would emerge and throw bricks at the private guard in the wagon. If they take control of the wagon, workers would drive it into a ditch or off a bluff into the Missouri River.

The fierceness of the women strikers in these street battles exposed the owners' lies about workers' "happiness."

The laundry owners worked closely with the widely hated Employers' Association to try to break the strike, and in the process, helped to galvanize local labor leaders into the fray.

On March 13, the day before the call for a general strike was supposed to be made, laundry owners tried to blame two strikers for the ambush and murder of a private laundry guard. But labor leaders went ahead with the call anyway. The strike was set for March 27.

ON THE first day of the strike, building trades, electricity plant and brewery workers, barbers, and porters walked out on their jobs and joined a four-block-long crowd that shut down several commercial laundries throughout the afternoon.

A police department wagon was stopped a block from the Labor Temple by 1,000 strikers, who freed three prisoners inside before setting the paddy wagon on fire. Private guards at one laundry fired their guns into the crowd outside, fatally injuring a striking laundry driver, Alonzo Millsap.

As the executive of the general strike committee pleaded with strikers to come to a nearby park to listen to labor speakers, one paper quoted the strikers as saying, "We don't want to hear any stump speeches now. What we want is action in wrecking" another commercial laundry building.

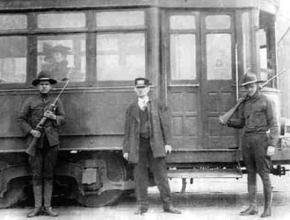

Groups of strikers moved to downtown late the first night, attacking hotels, restaurants and cafes. Locally stationed National Guardsmen were immediately mobilized downtown with machine guns.

Streetcar workers, who had only recently won union recognition in August, joined the sympathy strike the evening of the second day, breaking their new contract. The streetcar company resumed service the following evening with heavy National Guard protection.

Despite this, large crowds destroyed at least two trolleys anyway during the few hours they ran. Local police fired into the crowds and swung their billy clubs indiscriminately. The streetcar company ran partial service without incident on the fourth day.

Strikers shut down the printing offices of unionized typographical workers who refused to join the general strike. The musicians' local, which also refused, found a stick of dynamite outside their building.

Many of the women laundry strikers were Black--a remarkable fact for 1918, a year sandwiched between the white terror in East St. Louis in 1917 and race riots in the summer of 1919, when white mobs viciously targeted African Americans in several cities.

Prior to Kansas City's general strike, laundry strikers gathered at a Jim Crow hotel in February to testify about working conditions to sympathetic local Progressive women reformers. When the white strikers found out their Black comrades had been barred entry, they immediately left in solidarity.

This instance of working-class solidarity built on the interracial meatpacking strike that happened in September 1917--which was followed by hundreds of Black domestic workers signing up to form their own union a couple months later.

THE FIFTH day of the general strike was Easter Sunday, and remained fairly quiet. The strike committee allowed theaters and movie houses to operate for the holiday.

Bakers joined the general strike the following day, after days of intense pressure from the Missouri Council of Defense not to strike. St. Louis bakers refused to bake extra loaves for Kansas City baking companies in solidarity with the strike.

The general strike officially came to a close the seventh night in the form of a truce. No union recognition was granted to laundry workers. Strikers would be hired back, but no scabs would be fired.

The end of the general strike was met by confusion around the city. Streetcar workers who showed up to work were told they couldn't work wearing their union buttons any longer--so they promptly walked off the job again before the streetcar company backed down several hours later.

Building trades workers were locked out over their own demands for higher wage scales. Many restaurants remained closed when about 1,200 cooks, waiters and waitresses refused to return to work until they achieved better working conditions.

Polls for a municipal election closed just a few hours before the general strike ended. The labor movement and progressives sympathetic to workers had formed a third party for the election, in a failed attempt to get union members in office who were not beholden to the local Democratic Party.

While the militancy of the working class during the First World War provided experience and practice in interracial solidarity, the strike activities had not yet developed to the point that the logic of the two-party system could be overcome.

Many white workers remained loyal to the Democratic Party, while many Black workers saw an alternative in voting for a Black lawyer on the Republican ticket for 8th Ward Alderman. More radical workers likely stayed home, as they saw the third party as too watered down to represent workers' interests, and the elections clerk prevented the Socialist Party from making it on the ballot.

ALTHOUGH WARTIME inflation and capitalists' drive for profits provided the motivation for militancy, and tighter labor markets gave workers the opportunity to act, the war also complicated the general strike.

Many of the most important local industries were located in Kansas City, Kansas. Meatpacking workers and soap manufacturing workers worked on some of the biggest government wartime contracts in the area.

They had walked out in September for union recognition, and opted not to risk another wartime action with a sympathy strike.

The general strike committee originally included waterworks employees in their strike call, causing panic across the city. They later reversed their decision, which only led to more confusion.

Labor leaders also tried to maintain the appearance of reasonableness and patriotism to prevent the state from simply arresting the leadership, amid wartime hysteria and the persecution of socialists and other radicals. This played a role in keeping the full force of workers' power from being unleashed.

The legacy of the general strike lived on in the streetcar union, however. After months of threatening to strike if the transit company introduced women conductors, they shifted course and embraced women's membership in the union.

According to Maurine Weiner Greenwald's Women, War, and Work: The Impact of World War I on Women Workers in the United States, this is the only such instance in the country of a streetcar union including women.

As cold weather returned in late 1918 and the Spanish Flu wrecked the country, thousands of men and women streetcar workers went on strike for equal pay for women conductors. The months' long strike was unsuccessful, and returning soldiers were hired on as replacements.

First World War-era workers' activities highlight the militant history of Kansas City workers--and show that the collective action of workers opens up new possibilities for solidarity across race and gender.