From quagmire to defeat

The war in Vietnam resulted in the greatest military defeat ever suffered by the United States. Ever since, the U.S. ruling class and its intellectual pundits have had to try to overcome what has become known as the "Vietnam Syndrome"--the fear of the American ruling establishment that any large-scale military engagement might become a "quagmire" and provoke mass domestic opposition.

is a regular contributor to the International Socialist Review and a columnist on film and television for SocialistWorker.org.

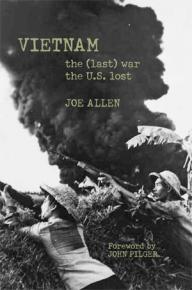

He is the author of a new book, Vietnam: The (Last) War the U.S. Lost, an examination of the lessons of the Vietnam era, with the eye of both a dedicated historian and an engaged participant in the movement against today's U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Here, with permission, we publish excerpts from one of the book's later chapters.

THE YEAR following the Tet Offensive of 1968 was the bloodiest year of the American war in Vietnam. As revenge for the humiliation suffered during the Tet Offensive, the United States unleashed a frightening wave of destruction. Despite the huge military cost to the National Liberation Front (NLF), it was clear that the Tet Offensive had destroyed the ability of the United States to effectively prosecute its war in Vietnam. In response, President Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek re-election. In a close race against Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon was elected president, in part because he implied that he had a "secret plan" to end the war in Vietnam. "The greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peacemaker," he said in his inaugural speech. It is a testament to the political quandary that the American ruling class found itself in that an anticommunist militarist could package himself as a "peace" candidate.

Despite all the talk of peace, the war would continue for another four years. Almost as many Americans died in Vietnam during Nixon's presidency as in the Johnson years. How does one explain this? The incoming Nixon administration set itself the goal of bringing the American war in Vietnam to an end without it being seen as a defeat for U.S. imperialism. In attempting to achieve this, Nixon would not only raise to new heights the destruction the United States would inflict on Vietnam, but would widen the war into neighboring countries.

These war policies revived and deepened the antiwar movement in the United States. The antiwar movement would surge to the zenith of its strength, while soldiers, sailors and air force personnel began to rebel in larger numbers. A special commission appointed by Nixon to assess unrest on the campuses following the invasion of Cambodia, led by William Scranton, the former Republican governor of Pennsylvania, argued that the country was "so polarized" that the division in the country over the war was "as deep as any since the Civil War." Scranton declared that "nothing is more important than an end to the war" in Vietnam. It was the strength of this opposition that not only led to the final withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam, but also to the adoption of repressive measures by an increasingly paranoid Nixon administration that would lead to its downfall.

Opposition to the War Deepens

Nixon may have weathered the domestic storm of protest, but he was far from being in a secure political position. It became clear to him that any further efforts to expand the war with U.S. ground troops would risk another potential domestic upsurge. His Cambodia adventure lifted the lid on protest in communities that had seen little antiwar activity beforehand. This was particularly true among Mexican Americans.

One of the most important events of the antiwar movement that took place in the wake of the Cambodia bombings was the Chicano moratorium. "The war in Vietnam politicized the Chicano community," according to historian Rudy Acuña. "Although the Chicano population officially numbered 10 to 12 percent of the total population of the Southwest, Chicanos comprised 19.4 percent of those from that area who were killed in Vietnam. From December 1967 to March 1969, Chicanos suffered 19 percent of all casualties from the Southwest. Chicanos from Texas sustained 25.2 percent of all casualties of that state." This slow burn of casualty rates combined with a rising movement against racial discrimination and oppression made the war in Vietnam a particular flash-point of anger.

The Brown Berets, a revolutionary nationalist group of young Mexican American activists predominately from the Los Angeles area, formed the first National Chicano Moratorium Committee in 1969. They called their first demonstration against the war, in solidarity with the nationwide moratorium movement, on December 20, 1969, with two thousand participants. They staged another protest two months later on February 28, 1970, with about six thousand Mexican Americans in attendance. In March 1970, at the Second Annual Chicano Youth conference in Denver, it was decided to organize hundreds of local moratorium actions against the war that would culminate with a national event to be held in Los Angeles on July 29. In between the conference and the planned national moratorium were the invasion of Cambodia and the ensuing explosion of nationwide protest and the state murders of protesters at Kent State and Jackson State.

Los Angeles was infamous for the racism and violence of its police and sheriff's departments toward Mexicans. The violence of the virtually all-white Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department against the Mexican Americans grew ominously as the moratorium approached. Acuña captures both the confidence of the antiwar marchers and the quiet hatred of sheriff's deputies as the march began:

On the morning of the 29th contingents from all over the United States arrived in East Los Angeles. By noon participants numbered between 20,000 and 30,000. Conjuntos (musical groups) blared out corridos; vivas and yells filled the air; placards read: "Raza si, guerra no!" "Aztlan: Love it or Leave it!" as sheriff's deputies lined the parade route. They stood helmeted, making no attempt to establish contact with the marchers: no smiles, no small talk. The march ended peaceably and the parade turned into Laguna Park. Marchers settled down to enjoy the program; many had brought picnic lunches. Mexican music and Chicano children entertained those assembled."

Soon after the park filled, a small incident at a nearby liquor store gave the police what Acuña calls "an excuse to break up the demonstration." Five hundred helmeted, club-wielding deputies attacked the peaceful crowd in the park. Their number eventually grew to fifteen hundred as they occupied the park. Acuña again: "They moved in military formation, sweeping the park. Wreckage could be seen everywhere: baby strollers [were] trampled into the ground; Victor Mendoza, walking with a cane, frantically looked for his grandmother; four deputies beat a man in his sixties; tear gas filled the air."

There are many horror stories of racist violence from that day. "A Chicano when he allegedly ran a blockade; his car hit a telephone pole and he was electrocuted. A tear-gas canister exploded in a trash can, killing a 15-year-old boy." But the worst was the murder of Ruben Salazar, a popular reporter for KMEX-TV, the Spanish language station. He and two coworkers stopped at a local bar after covering the events at Laguna Park. Sheriff's deputies surrounded the bar and shot a ten-inch tear-gas canister into the building that hit Salazar in the head, killing him. Salazar was popular in the Mexican community, making a name for himself by exposing police racism. He had told coworkers that he received complaints and threats about his reporting from L.A. Police Chief Ed Davis. Salazar's killers were indicted by a federal grand jury for violating his civil rights, but they were acquitted in federal court. The events at the Chicano moratorium demonstrated not only the depth of anger toward the war but also the willingness of government to use violence against antiwar activists, particularly those who were people of color.

The invasion of Cambodia also accelerated opposition to the war in the military. Vietnam veterans would now assume a leading position in the antiwar movement, changing the face of the movement. Years later, H. R. Haldeman, Nixon's chief of staff, lamented, "If the troops are going to mutiny, you can't pursue an aggressive policy." Discontent was so high, and the cost of the war was cutting so deeply into the country, that support was collapsing even in military towns previously known for their strident pro-war stances. Jon Huntsman, a special assistant to the president, complained of the growing "antiwar sentiment in once hawkish San Diego," home of the Pacific fleet.

The war was no longer politically sustainable for Nixon, who was soon facing re-election. By April 1971, a Lou Harris poll revealed that by a margin of 60 percent to 26 percent, Americans favored continued U.S. troop withdrawals "even if the government of South Vietnam collapsed." There was a "rapidly growing feeling that the United States should get out of Vietnam as quickly as possible." On April 7, 1971, Nixon announced that another one hundred thousand U.S. troops would be withdrawn from Vietnam by the beginning of December, leaving roughly 184,000 still there. Though Nixon was reluctant to offer any deadlines for complete withdrawal, it seems clear in retrospect that the deadline he had in mind was the November 1972 election.

How deeply antiwar sentiment cut into the country was revealed in late April, beginning with the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) actions in Washington between April 19 and 23, followed on April 24, 1971 by a day of national demonstrations against the war. According to Tom Wells:

Throughout the morning of April 24, demonstrators flooded the Ellipse in Washington, the staging area for the day's march to the Capitol. Most were young. Rank-and-file unionists, GIs, and veterans were present in greater numbers than in past peace demonstrations. According to a survey by the Washington Post, more than a third of the protesters were attending such a demonstration for the first time. 'I'm a member of the silent majority who isn't silent anymore,' a 54-year-old-furniture storeowner from Michigan remarked. The survey found that fewer than a quarter of the protesters considered themselves radicals; most were liberals. At least thirty-nine members of Congress endorsed the demonstration. So large was the turnout for it that cars and buses carrying protesters were backed up for three miles at the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel by 11 a.m. Many of the occupants never made it to the demonstration.

The demonstration in Washington was estimated to have grown to about half a million by the end of the day, making it up to that date the largest single demonstration in American history. That same day in San Francisco, more than two hundred thousand people marched against the war.

The April 24 national demonstrations were followed by nearly a week of actions, culminating in an effort to shut down the federal government on May 3. Nixon declared Washington, D.C. "open for business," but upwards of seventy five thousand antiwar protesters scattered through out the city on May 3, blocking traffic, sitting in at various government buildings, and harassing political figures. The D.C. police, backed by the federal government, began mass arrests of demonstrators early in the morning. By 8:00 a.m., more than seven thousand had already been arrested, and more arrests were to come. It was open season on anybody the police didn't like. "Martial law might not have been declared, but it was in effect."

The city jails couldn't handle the numbers arrested so a makeshift outdoor detention camp was built near RFK Stadium, surrounded by an eight-foot-high fence. People were held without food, water, or sanitary facilities. "Calling this a concentration camp would be a very apt description," declared Dr. Benjamin Spock, who was also held in detention. The Black residents of Washington responded sympathetically to the protesters, giving them food, water, and other necessities. Federal Employees for Peace held a rally in Lafayette Park across the street from the White House in the middle of the police crackdown.

While the May Day protests were chaotic and didn't achieve their objective of shutting down the government, they did, in the words of a Ramparts article, send "shivers down its spine." The backlash against the federal government's martial law–like tactics proved to be a disaster for Nixon. Even such cynical insiders as CIA Director Richard Helms later admitted, "It was obviously viewed by everybody in the administration, particularly with all the arrests and the howling about civil rights and human rights and all the rest of it...as a very damaging kind of event. I don't think there was any doubt about that."

From the first Vietnam moratorium events in November 1969, to the explosion of rage following the following the Cambodian invasion, to the spring events of 1971, millions of Americans were drawn into political action against the war. The actions were become more militant, more working class, more multiracial, and more left wing. In mid-November 1972, Nixon announced that another forty-five thousand U.S. troops would be withdrawn from Vietnam leaving roughly 139,000 there in early 1972.

The American ground war in Vietnam was grinding to an end, but the bloody American air war continued to inflict unfathomable destruction on the people of Southeast Asia. While antiwar activity continued into 1972, it was much smaller; the movement too had already reached its zenith.

Did the Large Demonstrations Make a Difference?

"We had an agenda we wanted to implement, and the principal impediment to that objective in Vietnam was the mass demonstrations, given aid and comfort and support by the liberal media, which was attacking the president constantly."

--Pat Buchanan, Nixon White House aide and speechwriter

One of the lingering debates concerning the antiwar movement of the 1960s was the effectiveness of the many national demonstrations in stopping or not stopping the war in Vietnam. This debate existed from the very beginning to the very end of the antiwar movement. Soon after the first national demonstration against the war organized by SDS, leading SDS members concluded that national demonstrations were a waste of time. Every time proposals were advanced for a national protest, arguments would surface about the efficacy of mass demonstrations. Many student activists felt a vague sense that something more was needed. For example, before the October 1967 Pentagon March, the SDS national office declared, "We feel that these large demonstrations--which are just public expressions of belief--can have no significant effect on American policy in Vietnam. Further, they delude many participants into thinking that the 'democratic' process in America functions in a meaningful way."

It wasn't just SDSers who drew these conclusions; radical pacifist Dave Dellinger in 1971 noticed "a fatigue, a quasi-disillusionment" with legal, mass demonstrations, a view that they were "yesterday's mashed potatoes."

Part of the reason that many activists thought that mass demonstrations were ineffective was because both Johnson and Nixon claimed they weren't swayed by them, and simply because the war continued, year in and year out, no matter how big the protests got--at least until 1970, when large-scale pullouts began.

But there was also a more political aspect to the debate. As the movement radicalized, there were those in the movement who elevated the tactic of street fighting to the level of principle. On the other side, there were those who made a fetish of legal, mass demonstrations, to the point of actively discouraging more confrontational tactics on the grounds that they would deter mass participation in the movement.

The mass demonstrations were undoubtedly insufficient by themselves to force the United States out of Vietnam, but they played an important role in drawing in and educating new antiwar forces, as well as raising activists' confidence that the movement was widening its base and gaining overwhelming public support. Halstead offers the example of 13-year-old Raul Gonzales, who described the impact of running across the April 15, 1967, mobilization against the war in Kezar Stadium on San Francisco:

I didn't know what was going on. So I asked someone. They said it was a demonstration to get the troops out of Vietnam...Personally, I was against the war, but I didn't really know why. I thought maybe I was the only one against it. The rally impressed me...I had no arguments against the war. From talking to people at the demonstration, and listening to the speeches, I got arguments. It strengthened my feelings. I took the arguments I learned there and the literature that was being passed out and used that with my friends. Those who were wavering tended to side with me now that I had the facts and figures and the stuff I'd gotten at the demonstration.

Yet, at the same time, many activists were right in their conclusions that more than large, set-piece protests were necessary to end the war. Ultimately, it was a combination of protest at home (including mass demonstrations, sit-ins, civil disobedience, student strikes, etc.), rebellion among GIs, and the armed struggle of the Vietnamese people that forced the United States to get out of Vietnam. In all this, there was no Chinese wall between different forms of protest or tactics--from mass peaceful demonstrations to blockades, sit-ins, strikes, and so on. These different manifestations of protest flowed in and out of one another and often one led to the other. The role of mass protests was to mobilize the maximum public manifestation of antiwar sentiment--a kind of movement roll call--used to feed the movement's further growth in all its different manifestations.

The mass demonstrations also had an impact on soldiers, as well as on the movement's attitude to soldiers. Fred Halstead recalls how all this began at the October 1967 March on the Pentagon:

The army brought in several thousand troops--in addition to federal marshals and police--to defend the Pentagon. Most of the troops were ordinary soldiers acting as military police for the weekend. Of those who confronted the crowd a few were angry, even brutal. But many were visibly embarrassed by the situation, and some became friendly in the course of contact with the demonstration. Word of this spread among the demonstrators, and afterward throughout the movement as a whole.... Before the Pentagon action, the idea of reaching GIs was pressed by a minority. After the October 21, 1967 march, the movement as a whole began to embrace the idea with some enthusiasm.

The impact of mass demonstrations on American GIs around the world only grew as the war went on. It would be hard to see how soldiers, sailors, and airmen would have moved against the war in such large numbers without the impact of millions marching against the war at home.