Munch’s very real phantoms

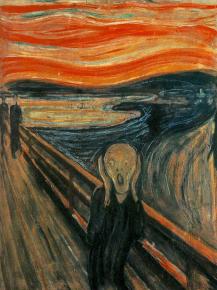

In celebration of the return of "The Scream" to museums, recounts the painting's remarkable life, and that of its creator, Edvard Munch.

FOUR YEARS after it was stolen by masked gunmen in broad daylight, and two years after it was recovered in still undisclosed circumstances, "The Scream" has gone back on display at the Munch Museum in Oslo.

"The Scream" is one of the world's best-known and widely reproduced painted images, and its return to the public gaze is being properly celebrated. Nonetheless, as I examined the merchandise on sale at this remarkable museum--the T-shirts, coffee mugs, mouse pads, all adorned with the familiar image--I couldn't help but feel that, in this case familiarity, has bred an alienating fog. The shock of the image has dissipated.

Of course, such is Edvard Munch's genius that it takes only a little quiet time in the presence of the actual painting to recover a sense of its depth and sublimity, to be shocked anew.

Recognized for a century as an outstanding representation of the crisis of the modern individual, an emblem of our times, "The Scream" has its origins in a personal experience recalled by Munch some years after it happened:

I was walking along a path with two friends--the sun was setting--suddenly the sky turned blood red--I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence--there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city--my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety--and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.

The setting is the gentle Oslofjord, a landscape Munch loved. After his nervous breakdown and subsequent return to Norway in 1908, he was to spend his life on its shores. But in "The Scream," it's molten, convulsed, a compound of liquid fire and animated darkness. Every bold, quivering, controlled brush stroke contributes to the sense of vertiginous motion.

Projecting out of this vortex is the extraordinary figure at the center of the composition: a wisp of humanity, hollow-cheeked, round-eyed, with hands clasped around its ears, as if to block out the reverberating sound: a sound which may or may not be issuing from the dark open mouth. It's almost a fetal position, assumed by a naked, vulnerable body in response to some nameless general assault by the outside world.

In Norwegian, the title is "Skrik," which might more accurately be translated as "shriek." The muteness of the medium muffles--and amplifies--the "infinite scream passing through nature." Munch evokes a cry that no recorded sound could ever measure up to. A scream so loud, so profound, it fragments the physical world--yet no one hears it. The friends in the background continue their walk. The terror is private, yet ubiquitous.

Typically of Munch, he brooded on the original experience for several years before producing the image (in 1893, when he was 29). Equally typically, having produced the image, unearthed it from inside at no little cost, he could not be satisfied with a single version, and for the next two years, reiterated it in various media.

The Munch Museum's "Scream" is painted in tempera on cardboard (making it tricky to repair the damage inflicted during the theft). Across town, in Oslo's National Gallery, there's another version in oil on canvas (which has also been stolen, back in 1994). In addition, there are lithographs and woodcuts, with countless variations in color. For Munch, this was not just a painting; it was an archetype, part of an elemental emotional language.

SO IT might be argued that the T-shirts and mouse pads are merely extensions of Munch's own practice. The wars and genocides of the 20th century made the image seem prophetic, as did the rise of psychoanalysis. In the nuclear age, Munch's Oslofjord looked aglow with a radioactive firestorm.

But the image's presence in popular culture goes beyond that. Warhol gave it his silkscreen treatment, along with Marilyn and the soup can; it's turned up in advertisements, in The Simpsons, in Shah Rukh Khan's remake of Don, and it is the inspiration for the mask worn by Ghostface in Wes Craven's Scream series.

All of which is, in some way, a tribute to the power of Munch's creation, even as it saps some of that power. For Munch himself, the public appropriation of this out-crop of his inner world would have been deeply disconcerting. "I do not believe in art if it does not arise from the creator's urge to open his heart," he wrote.

His credo of artistic authenticity may seem dated or naive now (though not to me), but as a visit to the Munch Museum makes palpable, there is a concrete bond between the artist and the artwork. Much of Munch's power is tactile; it's in the texture of the paint and the canvas, and you get only a hint of that in reproductions.

A visit to the museum also makes clear that there's much more to Munch than "The Scream," or the other famous images created in the 1890s. Personally, I prefer Munch when he's more himself: less desperate to universalize. Landscapes that are monumental yet evanescent; subtly observed portraits and especially self-portraits; majestic colors.

Always, Munch is striving for something original: his compositions are deeply considered and full of surprises. And always, he is painting with a purpose, working to give form to what he called "new-born thoughts that still have not taken shape."

Part of Munch's genius lies in his evocation of isolation; but though mentally embattled from an early age, he was not an entirely isolated genius. As a young man he was drawn into Oslo's bohemian counter-culture, where he was exposed to anarchist and revolutionary ideas.

He enjoyed friendships with a wide range of contemporary Scandinavian and European artists and writers, who saw Munch's work as part of a broader avant-garde challenge to a complacent establishment. An establishment that reacted accordingly, condemning the subject, tone and technique of Munch's groundbreaking paintings of the 1890s. He was not accepted as the master he obviously was until he was past 40.

In 1937, the Nazis condemned Munch's work as "degenerate" and sold off the scores of Munch paintings held in German museums. When they occupied Norway in 1940, Munch refused to have anything to do with them. He confessed to a friend that the "phantoms" that had haunted him for years had been put in the shade by the giant "phantom" at loose in the real world.

So my own tribute to Munch is a resolution never to wear "The Scream" on a T-shirt. It's a motif that shouldn't be trifled with.

First published in the Hindu.