Save the C.L.R. James library

explains the legacy of writer and historian C.L.R. James--and why people are challenging the renaming of the C.L.R. James Library in London.

ONE OF the turning points in my life came in 1988, upon discovery of the writings of C.L.R. James. The word "discovery" applies for a couple of reasons. Much of his work was difficult to find, for one thing. But more than that, it felt like exploring a new continent.

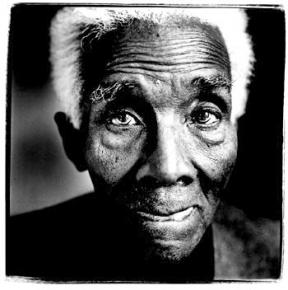

James was born in Trinidad in 1901, and he died in England in 1989. (I had barely worked up the nerve to consider writing him a letter.) He had started out as a man of letters, publishing short stories and a novel about life among the poorest West Indians. He went on to write what still stands as the definitive history of the Haitian slave revolt, The Black Jacobins (1938). His play based on research for that book starred Paul Robeson as Toussaint L'Ouverture.

In 1939, he went to Mexico to discuss politics with Leon Trotsky. A few years later--and in part because of certain disagreements he'd had with Trotsky--James and his associates in the United States brought out the first English translation of Karl Marx's Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. (By the early 1960s, there would be a sort of cottage industry in commentary on these texts, but James planted his flag in 1947.)

He was close friends with Richard Wright and spoke at Martin Luther King Jr.'s church. At one point, the U.S. government imprisoned James on Ellis Island as a dangerous subversive. While so detained, he drafted a book about Herman Melville as prophet of 20th century totalitarianism--with the clear implication that the U.S. was not immune to it.

Settled in Britain, he wrote a book on the history and meaning of cricket called Beyond a Boundary (1963). By all accounts, it is one of the classics of sports writing. Being both strenuously un-athletic and an American, I was prepared to take this on faith. But having read some of it out of curiosity, I found the book fascinating, even if the game itself remained incomprehensible.

This is, of course, an extremely abbreviated survey of his life and work. The man was a multitude. A few years ago, I tried to present a more comprehensive sketch in this short magazine article, and edited a selection of his hard-to-find writings for the University Press of Mississippi.

In the meantime, it has been good to see his name becoming much more widely known than it was at the time of his death more than two decades ago.

This is particularly true among young people. They take much for granted that a literary or political figure can be, as James was, transnational in the strongest sense--thinking and writing and acting "beyond the boundary" of any given national context. He lived and worked in the 20th century, of course, but James is among the authors the 21st century will make its own.

SO IT is appalling to learn that the C.L.R. James Library in Hackney (a borough of London) is going to be renamed the Dalston Library and Archives, after the neighborhood in which it is located. James was there when the library was christened in his honor in 1985. The authorities insist that, in spite of the proposed change, they will continue to honor James.

But this seems half-hearted and unsatisfying. There is a petition against the name change, which I hope readers of this column will sign and help to circulate.

Some have denounced the name change as an insult, not just to James's memory, but to the community in which the library is located, since Hackney has a large Black population. I don't know enough to judge whether any offense was intended, but the renaming has a significance going well beyond local politics in North London.

C.L.R. James was a revolutionary; that he ended up imprisoned for a while seems, all in all, par for the course. But he was also very much the product of the cultural tradition he liked to call Western Civilization. He used this expression without evident sarcasm--a remarkable thing, given that he was a tireless anti-imperialist. Given his studies in the history of Africa and the Caribbean, he might well have responded as Gandhi did when asked what he thought of Western Civilization: "I think it would be a good idea."

As a child, James reread Thackeray's satirical novel Vanity Fair until he had it almost memorized; this was, perhaps, his introduction to social criticism. He traced his ideas about politics back to ancient Greece. James treated the funeral oration of Pericles as a key to understanding Lenin's State and Revolution.

And there is a film clip that shows him speaking to an audience of British students on Shakespeare--saying that he wrote "some of the finest plays I know about the impossibility of being a king." As with James's interpretation of Captain Ahab as a prototype of Stalin, this is a case of criticism as transformative reading. It's eccentric, but it sticks with you.

Harold Bloom might not approve of what James did with the canon. And Allan Bloom would have been horrified, no doubt about it. But it helps explain some of James's discomfort about the emergence of African-American studies as an academic discipline. He taught the subject for some time as a professor at Federal City College, now called the University of the District of Columbia--but not without misgivings.

"For myself," he said in a lecture in 1969, "I do not believe that there is any such thing as Black studies. There are studies in which Black people and Black history, so long neglected, can now get some of the attention they deserve...I do not know, as a Marxist, Black studies as such. I only know the struggle of people against tyranny and oppression in a certain political setting, and, particularly, during the past 200 years. It's impossible for me to separate Black studies from white studies in any theoretical point of view."

James' argument here is perhaps too subtle for the Internet to propagate. (I type his words with mild dread at the likely consequences.) But the implications are important--and they apply with particular force to the circumstance at hand, the move to rename the C.L.R. James Library in London.

People of Afro-Caribbean descent in England have every right to want James to be honored. But no less outspoken, were he still alive, would be Martin Glaberman--a white factory worker in Detroit who later became a professor of social science at Wayne State University. (I think of him now because it was Marty who was keeping many of James' books in print when I first became interested in them.)

James was the nexus between activists and intellectuals in Europe, Africa and the Americas, and his cosmopolitanism included a tireless effort to connect cultural tradition to modern politics. To quote from the translation he made of a poem by Aimé Cesaire: "No race holds the monopoly of beauty, of intelligence, of strength, and there is a place for all at the rendezvous of victory."

Having C.L.R. James's name on the library is an honor--to the library. To remove it is an act of vandalism. Please sign the petition.

First published at Inside Higher Ed.