On the stage of history

In his column for Inside Higher Ed, reviews a recently rediscovered play written by the great historian and revolutionary C.L.R. James.

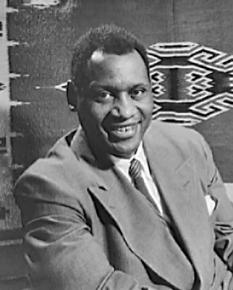

SOMEWHERE AMONG the boxes of notebooks in my study is the rough draft of a paper from the 1990s in which I started to pull together a paper on Toussaint Louverture, a play by C.L.R. James produced in London in 1936. Paul Robeson, in the title role, played the military genius who led a slave revolt on the island then known as San Domingo to its ultimate triumph--the creation of the republic of Haiti.

It was intriguing to know that James--who went on to tell the story in detail in The Black Jacobins (1938), one of the great works of historical narrative published in English over the last century--had first experimented with putting the events on stage. And the circumstances were certainly rich. Born in Trinidad in 1901, James had arrived in England in 1932 with the manuscript of a novel in his luggage and the distinction of having had a short story included in an anthology of the best short fiction for 1927.

He spent some time with the Bloomsbury literati, but grew ever more preoccupied with the social and political upheaval of the Depression years: the rise of Hitler, the scarcely more appealing reign of Stalin, economic disaster on all continents, the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini's fascist troops...

By the time his play was staged in 1936, James belonged to both the anti-Stalinist left and a network of African and Caribbean activists in London. Among them were students who later became leaders of their countries, including Jomo Kenyatta from Kenya and Eric Williams of Trinidad.

So James's play about a revolutionary leader defeating brutal oppressors was both a historical drama and a response to the news of the day. The fact that Toussaint was played by Paul Robeson--star of stage and screen, one of the world's most famous actors and singers, Black or otherwise--made it an event of international interest.

Unfortunately, the script had disappeared. Or rather, all of it had except a scene that appeared in a literary journal at the time, which I tracked down, along with a few reviews in newspapers. I studied The Keys, the official journal of the League of Coloured Peoples, a British organization that had helped sponsor the performance.

Also to be considered--though hard to research--was the role of the International African Friends of Abyssinia (as Ethiopia was called), of which James was a founder. Between gut instinct and dumb luck, I located a few other documents and connections that would help put the surviving fragment of the play into context.

The effort took a couple of months. The results could probably be duplicated today in a single morning using search engines and digital archives. (Best not to dwell on that; it causes growling.) Experience shows that devoting so much time and effort to research inspires a more proprietary attitude towards one's findings than downloading does. And so for more than a dozen years, I fully expected to return to the project--one of these days.

"One of these days" is an expression signaling that you've given up every part of an ambition except for the ghost of hope. (He who hesitates...) So, yes, there was a pang at first hearing about Toussaint Louverture: The Story of the Only Successful Slave Revolt in History. A Play in Three Acts (Duke University Press), edited by Christian Høgsbjerg, who discovered the long-lost manuscript while doing archival research for his dissertation on James. (He is currently a lecturer in history at Leeds Metropolitan University.)

But the volume is so thoroughly researched and intelligently prepared that my chagrin never stood a chance. The pang gave way to deep respect upon seeing the table of contents. Toussaint Louverture is easily one of the two or three most important publications of C.L.R. James's work in decades--and the best-edited, by a very large margin.

BESIDES THE script itself, it assembles an extensive and probably exhaustive dossier of notices and reviews of the play, as well as several relevant essays by the playwright that have never been reprinted until now. Some are not even listed in the available bibliographies of James' work. Høgsbjerg also includes the version of one scene from the play that appeared in a British literary journal, which shows that James revised it considerably in places.

The book contains a reproduction of the theater program for Toussaint Louverture and a stunning publicity shot of Paul Robeson in costume. (The latter also appears on the book's cover.) Høgsbjerg's introductory essay of about 40 pages situates the play and its performance into cultural and political context with considerable insight and finesse, and is one of the best-informed pieces of scholarship on any aspect of C.L.R. James's life and work ever published. The notes alone are more substantial than some books on the author.

In the introduction, Høgsbjerg recounts how he discovered the script in 2005, while going through the papers of Jock Haston, one of James' comrades from British Trotskyist circles in the 1930s. While working in the archives at the University of Hull, he noticed that the finding aid listed a file titled "Toussaint Louverture," but, thinking that it probably contained reviews or a playbill, concentrated instead on other folders containing memoranda and correspondence from factional disputes of long ago. At the end of his trip to the archive, Høgsbjerg opened the Toussaint file to find, with astonishment, "a yellowing mass of thin oilskin paper" containing the typescript of James's play.

When I asked him about it by em-ail, Høgsbjerg replied -- in a nice example of British understatement -- that the discovery "was in a sense not particularly remarkable, nor really mine to make, for several versions of the playscript lay languishing in a number of archives internationally."

Be that as it may, those other versions were languishing for the simple reason that they remained unknown. Someone who came across the script over the past 20 years might well have assumed it was already in print: there is a play from the late 1960s called The Black Jacobins that appears in The C.L.R. James Reader (Blackwell, 1992), where it is incorrectly dated as having been written in 1936. Given that other historians used Haston's papers without recognizing the manuscript's significance, it seems fair to say that Høgsbjerg's discovery was both remarkable and his to make. Chance favors the prepared mind.

Nor does the synchronicity end there. "In a sense," Høgsbjerg said by e-mail, "it is perhaps fitting that a play written about slavery and abolition should turn up in Hull, the hometown of William Wilberforce." James's manuscript surfaced a couple of years before the bicentennial of the British abolition of the slave trade--which the Tory politician had fought for over the course of 20 years, as depicted in the film Amazing Grace.

But it was only in 1833 that slavery itself was abolished throughout the British Empire--an anniversary that James celebrated in a couple of essays from 1933 (one originally read by the author on BBC radio) reprinted in Toussaint Louverture.

James wrote the play the following year, but it remained unproduced until 1936, when the script came into the hands of Robeson, who had been looking for a chance to portray the Haitian leader on stage. Reviews were mixed, but by all accounts, Robeson's performance was typically outstanding. The first performance received an ovation. Broadway made noises of interest, and a couple of critics suggested it would adapt well to screen, though nothing came of either possibility.

James was, Høgsbjerg stressed, "acutely conscious of the need to challenge the mythological British nationalist narrative of abolition, one that glorified the role played by British parliamentarians such as Wilberforce. Indeed, in the original version of the playscript, C.L.R. James mentioned Wilberforce himself in passing, but then later, in a handwritten revision (one that I have respected), decided to remove the explicit mention of the abolitionist Tory MP." The revision was almost certainly made "to help bring home the essential truth about abolition--that it was the enslaved who abolished slavery themselves--to a British audience who would almost certainly be hearing such a truth for the first time."

TWO WAYS of looking at the play are possible, it seems to me. One is as a document--an artifact of historical, political or biographical significance--and the other is as a work of art. The editor's introduction is invaluable for framing the script as a document, but the work of assessing it as a piece of theater is a much more subjective effort.

Historical dramatists always face the challenge of stuffing as much exposition as possible into the characters' mouths without making them sound like a textbook. My impression is that James did this with more finesse in some scenes than others, and that the play always improves when Toussaint takes the stage.

And all the more so, of course, when the reader imagines Robeson delivering the lines. But now that the script is in print, it seems time for someone to rise to the challenge of putting it on the boards, or on the screen. In case anybody considers doing so, I went ahead and asked Høgsbjerg to play dramaturg. He responded:

I would recommend to anyone attempting to restage Toussaint Louverture now to have the confidence to utilize the full 1934 postscript without making revisions, as I think James' play deserves to be performed at least once as he intended it. Only then will it be possible to really judge James as a playwright.

The 1936 production with Robeson unfortunately had three scenes cut, including all the scenes which explored the more personal side of Toussaint--his relationship with his wife and two children, scenes, which are important and revealing of how James saw the tension between Toussaint's loyalty to revolutionary France on the one hand and commitment to West Indian self-government and Black liberation on the other.

Considered as a document, the script seems deeply embedded in the world of the 1930s, but Høgsbjerg thinks James' treatment of "the most glorious victory of the oppressed over their oppressors in world history" will "remain an inspiration, because of its universal theme, for the foreseeable future."

At present, Høgsbjerg is co-editing a collection of papers on The Black Jacobins, which will appear in Duke's new C.L.R. James Archive series, of which with Toussaint Louverture is the first volume. Making an Opening: C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain, a revision of Høgsbjerg's thesis, is also forthcoming from Duke.

"If I never achieve anything else whatsoever as a historian in the course of my working life," he told me, "I will always be able to look back proudly at the small part I played in helping to ensure James' Toussaint Louverture--a piece of revolutionary literature--was out there, once again, for people to read, enjoy, learn from and indeed perhaps one day restage."

Again with the self-deprecation! But he's got something to be modest about.

First published at Inside Higher Ed.