The racist face of the housing crisis

Bloomberg Businessweek can't hide its racism--not after putting caricatures of African Americans on a cover illustration about the housing market. explains.

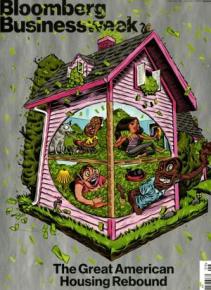

BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK stooped to a disgusting new low with a shockingly racist cover illustration for an article on the revival of the housing market. The illustration features caricatures of Blacks and Latinos--"with exaggerated features reminiscent of early 20th century race cartoons," as the Columbia Journalism Review's Ryan Chittum wrote--sitting in piles of cash.

The illustration echoes right-wing commentators who claimed "irresponsible" minority homebuyers borrowing beyond their means were responsible for the 2008 financial collapse. One of the most famous examples of this was Fox News' Neil Cavuto, who said, "I don't remember a clarion call that said, 'Fannie and Freddie are a disaster. Loaning to minorities and risky folks is a disaster.'"

The right wing and even mainstream publications repeated this line of argument ad nauseum in the wake of the crash, taking aim at government programs to encourage minority homebuyers such as the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act.

Of course, this argument is nonsense. The opposite is true: minority homeowners have paid disproportionately in the aftermath of the housing crisis due to the racist predatory lending practices of the big banks. Minorities were systematically charged higher fees and steered into riskier subprime loans even when they would have qualified for prime loans.

In 2011, Bank of America (BoA) agreed to pay out $335 million to settle allegations that Countrywide Financial--which BoA bought in 2008--discriminated against minority borrowers. That constitutes the largest residential fair-lending settlement in history.

According to the Department of Justice, "The odds of a minority applicant being steered into such a [subprime] loan were more than twice as high as those for a non-Hispanic white borrower with a similar credit rating."

Last year, Wells Fargo agreed to pay out $175 million due to similar allegations. According to the Washington Post, "The average African American taking out a $300,000 prime loan was charged $2,064 more in broker fees than a similarly qualified white customer. Latino borrowers paid an average of $1,251 more."

"They referred to subprime loans made in minority communities as ghetto loans and minority customers as 'those people have bad credit', 'those people don't pay their bills' and 'mud people,'" wrote former Wells Fargo loan officer Tony Paschal in his affidavit.

Whether or not all individual loan officers were racist, the overall pattern was endemic across the banking industry during the housing boom. As early as 2006, the Center for Responsible Lending found that "borrowers of color...were more than 30 percent more likely to receive a higher-rate loan than white borrowers, even after accounting for differences in risk."

The predictable result was that when the housing bubble burst, minority lenders were disproportionately affected. Again, according to the Center for Responsible Lending, African American borrowers were 76 percent more likely, and Latino borrowers 71 percent more likely, to have lost their homes to foreclosure than white borrowers. These disparities hold even when controlling for differences in income.

The report went on to estimate the "spillover" losses due to depreciating values of nearby properties in communities of color at upwards of $371 billion between 2009 and 2012 alone.

All this has accelerated the trend of a yawning wealth gap between whites and people of color. According to a recent study from the Institute on Assets and Social Policy at Brandeis University, the wealth gap between white and African American families has nearly tripled between 1984 and 2009. More than 25 percent of the gap is directly attributable to homeownership and other policies associated with housing.

According to the Pew Research Center, between 2005 and 2009, Latino wealth fell by 66 percent and Black wealth fell by 53 percent, compared with 16 percent for whites.

EVEN ABSENT these damning statistics, the Bloomberg Businessweek cover illustration would have been horribly offensive given the history of racist caricatures of people of color. In light of them, it's unforgivable.

Yet the artist contracted to illustrate the cover, Andres Guzman, claims he had no racist intention. Originally a native of Peru (though he now lives in Colorado), Guzman told Slate's Matt Yglesias, "I simply drew the family like that because those are the kind of families I know. I am Latino and grew up around plenty of mixed families."

Even if we give the artist the benefit of the doubt as to his intentions, the fact remains that no one on the (all-white and -male) editorial board saw a problem with sending it to print.

After the ensuing uproar, editor Josh Tyrangiel issued the following non-apology: "Our cover illustration last week got strong reactions, which we regret. Our intention was not to incite or offend. If we had to do it over again we'd do it differently." Note that Tyrangiel regrets the strong reactions, not the actual decision to run the cover.

Actually, the article that the cover was meant to illustrate doesn't mention race at all. Instead, it's a perversely cheerful piece on the rebound of Phoenix's housing boom--one of the cities that experienced the most dramatic rise and subsequent collapse in 2008.

Now, thanks to a wave of foreclosures, massive price depreciation and wholesale destruction of the local economy, property values and inventories have fallen so low as to encourage new investment--thereby laying the basis for the whole crazy bubble cycle to begin again.

The article states:

The price of homes in metropolitan Phoenix could rise 8.5 percent this year, according to Zillow's Humphries. Anything much higher than that would be worrisome, says nearly every economist who has looked at the city. Orr, the Cromford Report publisher, thinks people are still wary. "But knowing Arizona, we'll probably build too much at some point."

Given recent history, it should be clear who will pay the price if yet another housing bubble emerges and then inevitably bursts. Thankfully, there are signs of resistance to this insanity. In cities across the country, housing rights activists are fighting back, occupying homes to stop foreclosures and evictions and putting the banks' predatory lending practices on trial.

It will take nothing short of a national movement of this sort to take on the banks, who as we now well know use every means at their disposal--including the most vile racism--in their tireless pursuit of profit at our expense.