The lessons of cricket

In addition to its lessons about sports, C.L.R. James’ memoir about cricket explains a lot about the political development of the great revolutionary, writes .

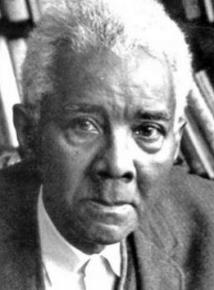

IN 2013, C.L.R. James' "cricket memoir," Beyond a Boundary, was republished to commemorate the 50th anniversary of its first edition. Most people familiar with James know that he loved and wrote about cricket, and many know that he played competitively as a young man in Trinidad.

It would be a mistake to think of cricket as a side interest completely separate from James' politics. It would also be a mistake to see a contradiction between James' love for cricket--a manifestation of colonialism--and his anti-colonial and anti-racist body of work.

Part of what makes Beyond a Boundary so extraordinary as a "sports book" and an autobiography of sorts is that the story James tells about his relationship with the game reveals quite a bit about his political development, and his political development shapes the story he tells about the game.

First, cricket was part of his rebellion against the "puritanism" imposed on the Black lower middle class in Trinidad by the constraints of race and class. Later, the cricket pitch was a source of pride as the only forum in which Blacks were permitted to excel. Eventually, it was part of his awakening to anti-imperialism and the "national question." Finally, as James developed as a Marxist, his understanding of how the sport emerged and changed and its importance to different classes became deeper and richer.

James says that to write critically about cricket, it is necessary to have played the game. The same can be said about watching cricket critically. For someone who didn't grow up in a cricket-playing country, or in one of the many communities in which cricket is played in the United States, it's possible to appreciate the beauty and skill of the game, and to understand objectively how one might become passionate about it. Without having swung a bat or bowled a ball, however, it seems impossible to acquire that passion or begin to absorb the complexities of the sport.

It is an elegant game, which gives it an air of aristocracy and imperialism. The white flannels, tea breaks and manicured pitches carved out of landscapes from the West Indies to South Africa to the Indian subcontinent to Australia all combine to highlight the fact that cricket was undeniably an imposition of empire. It can seem puzzling that nations starved, subjugated and exploited by the British Empire would retain such affection for the sport.

ON A trip to India in 2013, British Prime Minister David Cameron took the time to play cricket. As the odious tabloid The Sun put it, he played with "the locals" in Mumbai, adding, "David Cameron hit 'em for six yesterday--playing cricket with a 'slumdog' team in a city park."

On that same trip, Cameron visited the site of the 1919 Armristar massacre, during which the British army mowed down over 1,000 defenseless people and left them to die because of an evening curfew. Cameron said it was unnecessary "reach back into the past" to apologize.

In paying his "respects" to the memorial for the victims, Cameron decided it was appropriate to inscribe a memorial book at the site with a quotation from a predecessor, Winston Churchill, a virulent racist who caused millions of Indians to die by exporting food during a time of famine. Cameron emphasized that "mistakes" like Armristar did not mean Britain could not celebrate the positive legacy of empire, and he would undoubtedly count the shared love of cricket as part of that legacy.

Reading Beyond a Boundary, however, one has a sense that for the colonized, cricket had a different meaning than for the colonizer. By institutionalizing cricket, the British had created a visible contradiction to the racism on which imperialism was dependent. There was an ethical dimension to the game, which James revered as a boy and for which he unapologetically retained a life-long affection.

The imperialists could brutally suppress the West Indian people and deny them any opportunity to control their own destiny, but their ingrained loyalty to the game meant that within the boundaries of the cricket grounds, West Indians could assert their equality. They could also develop new styles of play, changing the game forever. To James, colonial cricketers were not playing the colonizers' game, they were making it their own.

James is aware that the system of oppression outside the boundaries affected the game, so cricket could offer only a temporary and incomplete respite. He says, "The British tradition soaked deep into us was that when you entered the sporting arena, you left behind the sordid compromises of everyday existence. Yet for us to do that we would have had to divest ourselves of our skins."

GROWING UP as the son of a teacher in Trinidad, James's bedroom window faced a cricket ground, and he was keenly interested in the game from a young age. Cricket and literature were both bound up in James' rebellion against what he called the "puritanism" of his lower-middle class family. Within the constraints of colonial society, Blacks could with great difficulty rise to a skilled trade, climbing one rung up the class ladder. James' grandfather had done so, but illness threatened the family's status.

James emphasizes how insecure the status of the lower middle class was, saying, "Respectability was not an ideal, it was an armor....the children grew up in unending struggle not to sink below the level of the Sunday morning top hat and frock coat."

James' father climbed another rung, becoming a teacher. The family expected James to use his obvious intellectual gifts to climb the next rung. Management, technical and business positions were closed, but it would have been possible for James to become a doctor or lawyer, the top positions open to Blacks. With luck and the good will of the white ruling elite, he could have been appointed to the Legislative Council, the pinnacle of Black achievement in colonial Trinidad.

While James rebelled against his intended fate, by his account, it was initially more personal than political. His interests in literature and cricket were both considered distractions, from which his father tried unsuccessfully to deflect him.

James was a very good player, so on graduating he looked for a cricket club to join for his "year of cricketing glory." Some clubs he ruled out because he was Black and not a light-skinned "colored man." It was unlikely he would be socially acceptable, regardless of skill level. Another he ruled out because it was made up of "plebians" with "no social status." He says he ruled this one out as easily as he did the clubs for which he was too Black.

He was left with two choices, a club with a high level of play comprised of Black clerks and teachers, and another, the club of the "brown-skinned middle class," which made an exception to its usual preference for light-skinned players and offered him a place. James accepted.

James is matter-of-fact in describing his deliberation over the social and racial implications of his choice, but concludes, "My decision cost me a great deal...Faced with the fundamental divisions in the island, I had gone to the right, and by cutting myself off from the popular side, delayed my political development for years."

After his playing days over, James taught and wrote occasionally about cricket. He became close to Learie Constantine, one of the greatest cricketers to come out of Trinidad, who later became a lawyer, politician and activist in England and Trinidad. James credits Constantine with playing a crucial role in his political development:

Puritanical as ever, I continued to view with apostolic disfavor any departure from the most rigorous ethics of the game...I was holding forth about some example of low West Indian cricket morals, when Constantine grew grave, with an almost aggressive expression on his face.

"You have it all wrong, you know," he said coldly.

What did I have all wrong?

"You have it all wrong. You believe all that you read in those books. They are no better than we."

I floundered around. I hadn't intended to say that they were better than we. Yet a great deal of what I had been saying was just that.

James's relationship with Constantine profoundly affected his political development, and moved him toward anti-imperialism and "the national question."

James accompanied Constantine to England, and ghost-authored a book with him. Constantine loaned him the money for the publication of his first political book, the version of The Case for West Indian Self-Government published in the West Indies. Constantine also helped him get established as a writer on cricket, which is how James supported himself while writing The Black Jacobins.

THE LATTER portions of the book represent James' return to actively thinking about cricket after his nearly 15 year sojourn in the United States. He notes that cricket had its origins in the games of farmers and artisans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with wealthy aristocrats sometimes providing subsidy, but not directing the development of the sport.

The class of the population that seems to have contributed the least was the class destined to appropriate the game and convert it into a national institution. This was the solid Victorian middle class.

James says that the bourgeoisie was motivated to create its own ideological and moral framework that rejected the self-indulgence and corruption of the Tory aristocracy, and the simmering radicalism of the working class. Sport was an instrument to inculcate "pre-Victorian" virtues into bourgeois youth. It was a reaction to Victorian society rather than a reflection. Sport was also a means of providing entertainment to the working class once factory reform created Sunday leisure time, but eventually became an end in itself.

James gives most of the credit for institutionalizing cricket to W.G. Grace. Grace was the first great "all-round cricketer," being dominant in batting, bowling and fielding. During a 30-year career beginning in the 1860s, Grace reinvented the sport and ushered in its "Golden Age."

He was nominally an amateur player, and James says he was deployed to help the amateur gentlemen of the great "public schools" (fee-paying boarding schools attended by the sons of the aristocracy and bourgeoisie) regain primacy over the professionals. James believes that cricket could not have achieved the social importance it eventually had if Grace had not become a folk hero to the masses at the same time he shored up the bourgeoisie's control over the sport.

To become firmly established in England and spread throughout the empire, James seems to say, cricket had to remain an important part of public school life, and also capture the imagination of the wider public. Sport has to serve two constituencies, it seems--the elites that help to establish its place in the culture, and the people who consume it as entertainment.

When he returned to Trinidad for a few years beginning in 1958, James successfully campaigned to have the first Black captain appointed to the West Indian cricket team, an achievement he considered important in promoting West Indian self-determination. He describes an eruption of bottle-throwing by fans against a controversial call favoring the visiting team when the England team played in Trinidad in 1960.

The political context for this seemingly minor incident was simmering resentment at local whites and the light-skinned privileged class for resisting the transition to self-government and the loss of privilege. The frustration was pervasive, but it found physical expression only when the crowd at a cricket match perceived the local officials favoring the white team of the imperial power.

It's a measure of James's value as a writer that a case can be made that Beyond a Boundary is one of the best books about a sport ever written, and yet it's hard to imagine anyone placing it among the three or four most important books that James wrote. It is, however, well worth reading, because of what it tells us about James' political development, and because of its much broader lessons about sports.

A game can be an expression of a dominant ideology, while also providing an outlet for the oppressed to assert themselves. Sport is always contested, meaning different things to the ruling class than to the working class and oppressed groups asserting their right to excel in play. The changes over time in a particular sport in some ways are as much the result of this ongoing competition as it is the changing styles and circumstances of competition among players on the playing field or court.