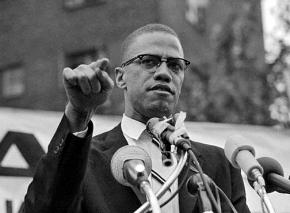

Malcolm X: A revolutionary life

In the first part of a SocialistWorker.org feature on the revolutionary politics and enduring relevance of Malcolm X, introduces the life of one of the 20th century's most important revolutionaries--starting with the world of racism and injustice that shaped him.

IF YOU want to know why mainstream Black History Month celebrations still pass uneasily over the legacy of Malcolm X a half-century after his assassination, take a moment to reflect on the Ferguson, Mo. uprising and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Then read these words from Malcolm, spoken at a 1964 debate at the Oxford Union in Britain:

No matter how many [civil rights] bills pass, Black people in that country, where I'm from, still our lives are not worth two cents...

So my contention is, we are faced with a racialistic society, a society in which they are deceitful, deceptive, and the only way we can bring about a change is speak the language that they understand. The racialists never understand a peaceful language, the racialists never understand the nonviolent language, the racialist has spoken his type of language to us for over 400 years. We have been the victim of his brutality; we are the ones who face his dogs, who tear the flesh from our limbs, only because we want to enforce the Supreme Court decision [of 1954 ending segregation in schools]. We are the ones who have our skulls crushed, not by the Ku Klux Klan, but by policemen, all because we want to enforce what they call the Supreme Court decision...

Well, any time you live in a society...and it doesn't enforce it's own laws, because the color of a man's skin happens to be wrong, then I say those people are justified to resort to any means necessary to bring about justice where the government can't give them justice.

Such statements alarmed the Democratic liberal establishment that was already worried about the increasing radicalization around the civil rights movement. So two months later, when Malcolm was gunned down at a February 21, 1965, at meeting in Harlem, the New York Times editorial board all but cheered:

Malcolm X had the ingredients for leadership, but his ruthless and fanatical belief in violence not only set him apart from the responsible leaders of the civil rights movement and the overwhelming majority of Blacks, it also marked him for notoriety and a violent end...Yesterday someone came out of the darkness that he spawned and killed him.

Yet even in death, Malcolm's influence continued to grow. When The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published a few months after his death, it became essential reading for a generation of African American students and young workers. Malcolm's willingness to speak the ugly truth about the horror and violence of racism in the U.S. had tremendous appeal at a moment when, despite the victory of the Southern civil rights movement, racism still festered in every corner of the country.

Lee Sustar examines the politics of Malcolm X as they were shaped by the world of struggle around him—and their meaning for today's strugglesThe legacy of Malcolm X

The closing chapters of the Autobiography described Malcolm's turn to politics and his search for a strategy to take the movement forward as it entered a new phase. After breaking with the Black separatist Nation of Islam in early 1964, Malcolm had embraced orthodox Sunni Islam and formed his own political organization.

He continued to call for both self-defense from racist attack and Black self-determination--an approach that went beyond the nonviolent tactics and integrationist perspective of Martin Luther King and other civil rights leaders. Even so, in the months before he was killed, Malcolm began to reach out to the left and even civil rights leaders that he had previously scorned, making an appearance in Selma, Ala., in a show of support for King, who had been jailed during the protests that culminated in the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Then, suddenly, Malcolm was gone--cut down before he could develop his ideas about the struggle for Black liberation and develop a program to achieve it. The wealthy and powerful were relieved. As Phil Ochs put it in his satirical song, "Love Me, I'm a Liberal:"

I cried when they shot Medgar Evers

Tears ran down my spine

I cried when they shot Mr. Kennedy

As though I'd lost a father of mine

But Malcolm X got what was coming

He got what he asked for this time

So love me, love me, love me, I'm a liberal

IN THE half-century since his assassination, Malcolm's legacy has slowly been deradicalized by politicians and Corporate America. Even the U.S. Postal Service issued a postage stamp bearing his image in 1999.

Certainly Malcolm is deserving of recognition. But despite some rare and welcome exceptions, such as Spike Lee's 1992 movie Malcolm X, the prevailing treatment of Malcolm today recalls the Russian revolutionary Lenin's comment about how revolutionary leaders, after their death, are reduced to "harmless icons" for the "consolation of the oppressed classes."

The defense of Malcolm's legacy has been left to a relatively small network of those who followed or were inspired by him. "It seems odd that very little attention is being devoted to the anniversary dates of the life and legacy of such an extraordinary leader," Ron Daniels, the veteran militant Black activist, wrote recently. Daniels, who helped to organize a big commemoration of Malcolm in 1990, lamented the lack of a similar effort today: "It is as if Black America is gripped by a case of historical amnesia."

Yet even among those who are determined to remember Malcolm and demonstrate his ongoing relevance, there are ongoing debates about just what his legacy means.

Was he a Black nationalist, even though he ultimately stopped describing himself in those terms in the final months of his life? Was he moving towards socialist conclusions, as some of his collaborators on the left have argued? Or would Malcolm have joined many of his contemporary African American activists in electoral politics and the Democratic Party, as suggested in the exhaustively researched biography written by the late Manning Marable?

This article will make no such definitive claims. It will, however, maintain that Malcolm stands squarely in the Black--and U.S.--revolutionary tradition.

Fifty years after his death--with an African American in the White House and thousands of Black elected officials and celebrities--Malcolm's injunction to militant self-defense against racist attack and his call for self-determination and Black liberation remain central to the politics of our time. Although he was killed before he could fully formulate his new perspective to achieve Black liberation, it is clear that the challenges Malcolm laid out can only be answered with a revolutionary transformation of U.S. society.

WHEN MALCOLM gave his trademark searing denunciations of racist violence, he was drawing upon personal experience with such horrors. Born Malcolm Little in 1925, in a period marked by a resurgence of the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan, Malcolm's earliest memories were shaped by racist violence and the struggle against it.

Manning Marable describes how his parents, Earl and Louise, were devoted followers of the Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, and Earl moved around the country to help build Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association. In Omaha, Neb., Earl, who worked as a carpenter and did odd jobs, ran head on into the Klan, which played a major role in both the Democratic and Republican parties and regularly held parades and picnics. The Klan came for Earl one night when he wasn't home. After Louise stood them down, they broke every window in the home to make their point.

The Little family later moved to Lansing, Mich., where a violent Klan offshoot, the Black Legion, held cross-burnings in the night. Soon, the family was facing eviction from their home because of a local law banning African Americans from purchasing land in the area. While Earl fought back in court, their home was burned down, almost certainly by white racists incensed by Earl and Louise's activism in the UNIA. Two years later, Earl was dead, supposedly from an accidental fall in front of a streetcar, although strong circumstantial evidence pointed to the involvement of racists who may have beaten Earl before pushing him onto the tracks.

Following Earl's death, Louise Little fell into poverty. She was soon unable to care for Malcolm and his seven siblings. Malcolm was sent to a foster home, and then sent away to school. He was told by a teacher that his goal to become a lawyer was "no realistic goal for a nigger." He dropped out of school and in 1941 moved to live with his half-sister Ella, a child from his father Earl's previous marriage.

Ella had regular run-ins with the law, and introduced Malcolm to hustling and petty crime. As Malcolm recounts in his Autobiography, he became a fixture at Boston's Roseland Ballroom, where he shined shoes for famous jazz musicians and the stars of the local nightlife scene amid the economic boom stimulated by he Second World War. He embraced the Black youth counterculture signified by zoot suits, a flashy style of dress deemed inappropriate by racist authorities, who thought such behavior unpatriotic during wartime.

Malcolm worked a series of low-wage jobs, eventually securing employment as a food vendor on railroads on the Northeast corridor, which allowed him to visit Washington, D.C., and New York City. He then got work on cross-country routes, enabling him to see the country. While living in wartime Harlem, he was exposed to the intellectual, cultural and political capital of Black America. As he later recalled, he also ran into Communist Party members selling their newspaper and campaigning for rent control and other issues.

He was in Harlem during the 1943 riot that followed a police officer's shooting of a African American serviceman. Perhaps reflecting the mood of young African Americans cynical about the U.S. claims to be fighting for freedom in Europe and Asia while maintaining Jim Crow segregation at home, Malcolm talked his way out of being drafted by telling an Army psychiatrist that he wanted to get the guns of the military to kill whites.

At the same time, he turned to drug dealing and other petty crime. While Marable argues that Malcolm later exaggerated his criminal activity in order to enhance his credibility on the street, Malcolm's hustles were enough to run him afoul of the law. Along with his friend Shorty and several others, he was convicted on charges of burglary in the Boston area and sent away to Massachusetts' Charlestown prison, a hellhole dating from the early 19th century.

It was in prison that he met John Elton Bembry--"Bimbi" in the Autobiography--whose impressive intellect convinced Malcolm to undertake a program of self-education. Later, after being transferred to another, more liberal prison aimed at rehabilitation, Malcolm was able to make use of better prison resources to pursue his path of self-development. At the same time, his siblings drew him towards the religious organization they had joined--the Lost-Found Nation of Islam (NOI).

THE NOI's call for Black separatism offered something familiar to the Little family, which had been steeped in Marcus Garvey's version of Black nationalism. NOI leader Elijah Muhammad, himself a former Garveyite, called for African Americans to develop their own autonomous society within the U.S., with their own businesses and institutions.

What Muhammad added was a theology that he'd adapted from a W.D. Fard in the early 1930s. Fard claimed that Blacks had once ruled the earth until an evil Black scientist had created whites--devils--who eventually took control of the planet. African Americans, in fact, were Asiatic Blacks, according to Fard, members of the lost tribe of Shabazz that had been kidnapped from Mecca nearly 400 years earlier. Fard, under pressure from authorities, disappeared in 1934. Elijah, who considered Fard to be Allah, took over the NOI.

After serving a prison sentence for draft evasion, Elijah Muhammad oriented the NOI on prisoners, drug addicts and the poor--people neglected by both the political system and the Black middle class. During his more than six years in prison, Malcolm was won over to the NOI by his family. He converted several other prisoners and organized alongside them for the right to practice their religion.

In the Autobiography, Malcolm recalled the bracing impact of the NOI's worldview:

Human history's greatest crime was the traffic in Black flesh when the devil white man went into African and murdered and kidnapped to bring to the West in slave ships, millions of Black men, women and children, who were worked and beaten and tortured as slaves.

The devil white man cut these Black people off from all knowledge of their own kind, and cut them off from any knowledge of their own language, religion and past culture, until the Black man in America was the earth's only race of people who had absolutely no knowledge of his true identity.

Meanwhile, Malcolm continued to read prodigiously, plunging through Western philosophy, African American history and the struggle against colonialism and imperialism. "Book after book showed me how the white man had brought upon the world's Black, brown, red and yellow people every variety of the sufferings of exploitation," as he put it in the Autobiography.

By the time of Malcolm's release from prison in 1952, he was prepared to build the NOI. Moving to Detroit, where the organization was headquartered, Malcolm encountered a small but vibrant organization that was systematically working to recruit from among the millions of African American working people who'd been drawn into Northern cities to take jobs in industries spurred by the wartime boom. Like many other NOI members, Malcolm abandoned his surname of Little as a legacy of slavery--and adopted X instead.

THE NOI's message of Black pride, separatism and self-defense found a ready audience in urban America. Although formal segregation laws did not exist in the North, Black workers nevertheless lived in segregated neighborhoods in declining central cities. The end of the Korean War hastened the deindustrialization of Northern cities. Throughout the 1950s--a time of general economic expansion--less than half the Black working class held full-time jobs year round. By 1960, the differential between Black and white unemployment had reached two to one, where it remains to this day.

In such conditions, the NOI--known popularly as the Black Muslims--flourished. With the destruction of the left during the anticommunist witch hunts of the 1950s, there was a dearth of anti-racist political organization. The Communist Party members who Malcolm regularly saw on the streets of Harlem in the 1940s were gone a decade later. Union leaders who had collaborated in the purge of "reds" from their ranks either shied away from any serious anti-racist struggles or openly opposed them. The Democratic political machines that ran most Northern cities had grudgingly made a place for a tiny number of Black elected officials, but these patronage-based networks were unable or unwilling to confront racist politicians or employers.

The NAACP, which had swung to the left under pressure in previous decades, became far more conservative, embracing the anticommunism of the Cold War and cautiously seeking a niche for the small African American middle class. Of course, the civil rights movement erupted onto this scene in the late 1950s, but because it was oriented on ending legal Jim Crow segregation in the South, it had relatively little to say to Black working people in the North.

What had begun in Detroit as a religious sect in the early 1930s grew into a movement of an estimated 100,000 members by 1961. According to historian Jack Bloom:

The bulk were laborers or unemployed. They were less directly concerned with the issue of segregation that confronted Blacks in the South except and so far as they identified with their kinsmen. But the treatment Blacks received in the South, and their own concerns, angered these ghetto Blacks. It was their anger that Malcolm X both articulated and encouraged.

Joining the NOI meant embracing a strict moral code: no tobacco, no alcohol, no sex other than between a married man and woman. The Nigerian-born academic E.U. Essien-Udom interviewed scores of NOI members in Chicago for his 1962 book Black Nationalism: A Search for Identity in America. Many told him that they had cut themselves off from family and friends outside the organization. "I look upon them with pity," a woman identified as Sister Nellie told the author. "When you accept Islam you stop drinking, smoking and committing indecent acts you used to do with them. They think that it is odd, and they think that you are insane."

According to Black sociologist C. Eric Lincoln's 1961 book on the organization, NOI members were disproportionately young and male, with older members typically having been involved in the Garvey movement or other Black-oriented Muslim groups. The great majority were workers--in factories or domestic service--with a scattering of intellectuals and college students among them. As Lincoln wrote:

The Muslim leaders tend to live and build their temples and businesses in the areas from which they draw their major support--in the heart of the Black Ghetto. This ghetto houses the most dissident and disinherited, the people who wake up to society's kick in the teeth each morning and fall exhausted with a parting kick each night. These are the people who are ready for revolution--any kind of revolution--and Muhammad astutely builds his temples in their midst.

Ultimately, however, Elijah Muhammad was opposed to taking practical steps to achieve that transformation--even as his main disciple, Malcolm, gravitated to the politics of revolution.

The next part in this series on "The Life and Legacy of Malcolm X" will appear next week.