The resistance to history’s enormous crime

In the second article in a series on slavery and the Civil War, describes how the revolutionary struggle to abolish slavery took shape in 19th century America.

THE RISE of the United States to become the richest nation ever known is bound up with one of the most barbaric crimes in all history--the enslavement of Africans to be laborers in the "New World."

It's impossible to overstate the horrors of the slave system that thrived in America right up until the Civil War ended it 150 years ago--the "Middle Passage" of kidnapped Africans transported across the Atlantic, costing the lives of one-sixth of the human "cargo"; families ripped apart on the auction block in genteel Southern cities; maximum violence used to extract the maximum possible labor from the slaves.

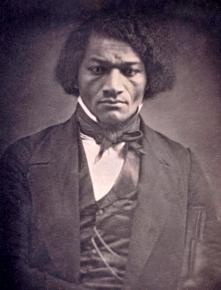

Plus, there was the day-to-day misery described by the former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass: "The overwork and the brutal chastisements of which I was the victim, combined with the ever-gnawing and soul-devouring thought--'I am a slave, and a slave for life, a slave with no rational ground to hope for freedom'--rendered me a living embodiment of mental and physical wretchedness."

But the history of slavery is also a history of resistance--one that is disgracefully ignored or downplayed today even more often than the system's atrocities are.

The first steps in the struggle were taken by slaves themselves, but the cause of abolition was taken up by Black and white, and grew into a massive movement by the middle of the 19th century--one that was more and more dedicated to the revolutionary overthrow of the slave system.

THE SLAVE resistance was rooted in countless small acts of defiance and opposition--feigning illness to avoid work or breaking tools to slow down the pace of work. Slaves developed a culture of resistance, too, converting work songs into expressions of their desire to be free--and, likewise, the Christianity taught to them by the masters.

In his autobiography, Frederick Douglass describes how his fury was directed at a violent overseer. "I was a changed being after that fight," Douglass wrote. "I had reached the point at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact, though I still remained a slave in form."

One hundred and fifty years ago, the institution of slavery was finally destroyed with the end of the Civil War. Socialist Worker writers tell the story.

Slavery and the Civil War

Slavery and the roots of racism

The resistance to history’s enormous crime

The road to the Civil War

To save the Union or to free the slaves?

The Civil War becomes a revolutionary war

Reconstruction after the war

More often than is commonly acknowledged, this spirit erupted in mass slave revolts. The most famous was the uprising in Virginia led by Nat Turner in August 1831, but there were more. Four years later, for example, an alliance of Native Americans, escaped slaves, plantation hands and free Blacks organized as a fighting force against the U.S. Army. The radical historian Herbert Aptheker documented more than 250 revolts on plantations and another 55 mutinies on slave ships.

None of these revolts was able to survive against the terrorist system run by the Southern slave owners, who could rely on the government at every level, up to and including the federal, to crush any uprising.

Despite the repression, a system to aid slaves escaping bondage--the Underground Railroad, supported by a variety of conspiratorial organizations in the U.S. and Canada--took shape and helped an estimated 100,000 people escape by 1850. Especially during the later years, most of the railroad's conductors were Black.

When the slave power tried to reach into the North to kidnap Blacks accused of being fugitives, it was met by direct action and not-so-civil disobedience led by those in the best position to know their enemy.

For example, in 1793, a Massachusetts lawyer named Josiah Quincy was defending a man accused of being a runaway slave. According to his biographer, as Quincy got up to make his argument, a group of Black people came into the courtroom--Quincy turned around and "saw the constable lying on the floor, and a passage opening through the crowd, through which the fugitive was taking his departure without stopping to hear the opinion of the court."

Before the slave system was finally overthrown 150 years ago, a majority of people in the North had turned against the Southern slaveocracy. But as Herbert Aptheker wrote, Blacks, whether enslaved or free:

were the first and most lasting Abolitionists...Without the initiative of the Afro-American people, without their illumination of the nature of slavery, without their persistent struggle to be free, there would have been no national Abolitionist movement. And when the movement did appear, the participation of Black people in every aspect was indispensable to its functioning and its eventual success.

BEYOND THE victims themselves, there was sentiment against slavery from the founding of United States. Leading voices of the American Revolution like Tom Paine and Benjamin Franklin recognized the hypocrisy of a country that claimed "all men are created equal" in its Declaration of Independence, but where 1 million people were owned as human property at the time.

But the dominant opinion was that slavery would eventually die out, and therefore nothing more than moral persuasion was needed. This view was proved wrong within a few decades of the founding of the U.S., and the reason why can be summed up in one word: cotton.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 made mass production possible at the moment when the Industrial Revolution, based on textile manufacturing, was taking off in Britain. In the next two decades, U.S. cotton exports grew from 500,000 pounds to more than 80 million pounds a year, representing a majority of American trade by a large margin.

The great fortunes of America and of Europe were founded on a system with slave labor at their heart. As Karl Marx wrote in a letter, "Without slavery there would be no cotton, without cotton there would be no modern industry."

So slavery didn't die away--the pace of exploitation was massively intensified. In the South, purely moral opposition to slavery fell away, and if it didn't, it was driven out. Abolitionism became centered in the North among supporters who inevitably reached radical conclusions--that slavery was not some stain that would eventually fade out, but a system that would have to be rooted out.

In 1827, a group of Blacks in New York launched an antislavery newspaper called Freedom's Journal. The distribution network for the paper was also a circle of political agitators who traveled widely to organize. Among the paper's agents was David Walker, whose Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World--published a little over a year before Nat Turner's revolt--struck fear into the hearts of Southerners.

The publications and political ideas put forward by Blacks, many of them escaped from slavery themselves, shaped a new generation of abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, a white Massachusetts printer and journalist. In 1831, he launched the weekly newspaper The Liberator, which would be a call to action to abolitionists breaking from old ideas. As Frederick Douglass remembered in his autobiography:

The paper became my meat and my drink. My soul was set all on fire. Its sympathy for my brethren in bonds--its scathing denunciations of slaveholders--its faithful exposures of slavery--and its powerful attacks upon the upholders of the institution--sent a thrill of joy through my soul, such as I had never felt before!

AT THE national level, slavery's grip grew tighter than ever in this era, both economically and politically. But the rise of the new phase of abolitionism showed that there was fertile ground in the North for a resistance to take root and spread.

By late 1837, Garrison estimated that there were "not less than 1,200 anti-slavery societies in existence"--a sixfold increase in just a few years, and with a total membership of more than 100,000 people.

This growth was the result of the hard work of political organizing--of the kind that radicals of every era, including today, would recognize.

Public meetings were probably the primary way that abolitionists reached their audience. In cities and towns across the North, dozens and hundreds and even thousands would pack into lecture halls to hear speakers.

The editor of Frederick Douglass' speeches and writings estimated that a "partial" list of speaking events for Douglass, just in one month in 1855, included at least 21 addresses, in cities from Maine and Massachusetts to New York and Pennsylvania. All told, between 1855 and 1863, Douglass gave more than 500 known speeches in the U.S., Britain and Canada.

Papers like Garrison's Liberator were chronically short of funds, but maintained a growing readership, even as the number of newspapers multiplied. Pamphlets, often based on the speeches of abolitionist agitators, reached hundreds of thousands of people. Published in 1845, Frederick Douglass' autobiography sold 5,000 copies in four months and some 30,000 by the start of the Civil War a decade and a half later.

After a yearlong petition campaign that began in 1837, the American Anti-Slavery Society announced that 414,471 people had signed a petition calling on Congress to end slavery and the slave trade in the District Columbia. Another petition drive to lift the gag rule on Congress discussing anti-slavery resolutions got 1 million signatures from across the Northern states.

Such accomplishments would have been impossible without a well-trained core of activists. Thus, Herbert Aptheker's Abolitionism describes a "school" organized in November 1836:

Theodore Weld had recruited about 50 people prepared to devote themselves to spreading the movement's message. Most of them attended what might well be called, in modern terms, a cadre-training school in New York City. From November 15 through December 2, these volunteer students heard the questions most commonly asked of abolitionists; suggesting appropriate answers were experts Theodore Weld, the Grimké sisters--Angelina and Sarah--William Lloyd Garrison, James G. Birney and others.

THIS NEW phase of abolitionism was unapologetically radical and uncompromising, but its main ideas can seem strange from the vantage point of today.

Garrison and his followers rejected involvement in politics. They believed slavery would be overthrown by building overwhelming moral pressure against the slave owners, that the anti-slavery movement must be nonviolent, and that the North should secede from the U.S. rather than remain united with the slave South.

But this represented a significant advance in a movement where the dominant belief had been that emancipation would come gradually, through existing institutions. The hostility to political involvement was a response to the corruption of a U.S. political system that accepted endless compromises with the slaveocracy--a system where the Constitution itself was "infected with the pestilence of slavery," as Garrison wrote.

The anti-slavery struggle was bound up with discussions and disagreements about these ideas, but Garrison's philosophy was the ground on which the debates began. Frederick Douglass was a devoted Garrisonian for a decade after his escape from slavery in 1838, until he helped lead a further radical transformation of the movement, directed toward engagement with politics.

One of the most famous critics of Garrison's insistence on nonviolence was the Black abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet, who called for a general strike of slaves at the National Negro Convention in 1843: "Let every slave throughout the land do this, and the days of slavery are numbered...Let your motto be resistance! resistance! resistance!" Yet Garnet's first political act while a student in New York City was to form the Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association.

What Douglass and Garnet recognized in Garrison, whatever their later differences, was a devotion to the struggle, no matter what sacrifice or suffering had to be endured. Another eventual leader of the movement, Wendell Phillips, remembered later that he first saw Garrison in 1835 when the Liberator editor was being dragged through the streets of Boston by a mob of anti-abolitionists who wanted to lynch him.

The radicalism of the abolitionists in this era came out on other social and political questions. For example, the anti-slavery struggle "was the first great social movement in U.S. history in which women fully participated in every capacity: as organizers, propagandists, petitioners, lecturers, authors, editors, executives and especially rank-and-filers," Aptheker wrote.

Abolitionists saw their fight against slavery as connected to an international one for democracy and freedom. Garnet, writing in Douglass' newly founded newspaper North Star, greeted the great wave of European revolts of 1848 as the sign of "a revolutionary age" in which "revolution after revolution will undoubtedly take place until all men are placed upon equality."

Until the 1850s at least, abolitionists were still a minority--often a persecuted one--in the North, where hostility to the Southern slaveocracy coexisted among many ordinary whites with hostility to the slave. Garrison in particular was known for chastising the labor movement in the Liberator. But on this issue, too, ideas shifted. In 1849, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society passed a resolution declaring:

Whereas the rights of the laborer of the North are identical with those of the Southern slave, and cannot be obtained as long as chattel slavery rears its hydra head in our land; and whereas, the same arguments which apply to the situation of the crushed slave, are also in force in reference to the condition of the Northern laborer--although in a less degree; therefore, Resolved, That it is equally incumbent upon the working men of the North to espouse the cause of the emancipation of the slave and upon Abolitionists to advocate the claims of the free laborer.

Abolitionists were determined to challenge racism among Northerners, including bigotry or paternalism within their own ranks--an absolute necessity in a struggle where Black abolitionists played a central role. The Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1838 adopted a resolution proposed by Sarah Grimké that insisted:

It is the duty of Abolitionists to identify themselves with these oppressed Americans, by sitting with them in places of worship, by appearing with them in our streets, by giving them our countenances in steamboats and stages, by visiting them in their homes, and encouraging them to visit us, receiving them as we do our fellow citizens.

AS THE 19th century continued, every year brought new confirmation of how the institution of slavery was woven into the fabric of American political and economic power. As Wendell Phillips explained in a speech in Boston in 1852--with Garrison alongside him on the platform:

Every thoughtful and unprejudiced mind must see that such an evil as slavery will yield only to the most radical treatment. If you consider the work we have to do, you will not think us needlessly aggressive, or that we dig down unnecessarily deep in laying the foundation of our enterprise.

A money power of two thousand millions of dollars, as the prices of slaves now range, held by a small body of able and desperate men; that body raised into a political aristocracy by special constitutional provisions, cotton, the product of slave labor, forming the basis of our whole foreign commerce, and the commercial class so subsidized, the press bought up, the pulpit reduced to vassalage, the heart of the common people chilled by a bitter prejudice against the Black race; our leading men bribed, by ambition, either to silence or open hostility; in such a land, on what shall an Abolitionist rely?...

[T]he old jest of one who tries to lift himself in his own basket is but a tame picture of the man who imagines that, by working solely through existing sects and parties, he can destroy slavery.

There were many economic and social factors driving what New York political leader William Seward called the "irrepressible conflict" between North and South. But in the first six decades of the 19th century, each time North and South came to the brink, the Northern business and political elite accepted a compromise that allowed the slaveocracy to continue to reign.

The revolutionaries of the abolitionist movement were essential in pushing that conflict to the breaking point at long last.