Still whistling “Dixie”

How did Dallas become the hub of far-right fanaticism in the 1950s and '60s? reviews a book that provides answers, in his column for Inside Higher Ed.

TRYING TO explain recent developments in the American presidential primaries to an international audience, a feature in a recent issue of The Economist underscores aspects of the political landscape common to both the United States and Europe. "Median wages have stagnated even as incomes at the top have soared," the magazine reminds its readers (as if they didn't know and had nothing to do with it). "Cultural fears compound economic ones" under the combined demographic pressures of immigration and an aging citizenry.

And then there's the loss of global supremacy. After decades of American ascent, "Europe has grown used to relative decline," says The Economist. But the experience is unexpected and unwelcome to those Americans who assumed that the early post-Cold War system (with their country as the final, effectively irresistible superpower) represented the world's new normal, if not the End of History. The challenges coming from Putin, ISIS and Chinese-style authoritarian state capitalism suggest otherwise.

Those tensions have come to a head in the primaries with the campaigns of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders: newcomers to their respective parties whose rise seemed far-fetched not so long ago. To The Economist's eyes, their traction is, if not predictable, then at least explicable: "Populist insurgencies are written into the source code of a polity that began as a revolt against a distant, high-handed elite."

True enough, as far as it goes. The analysis overlooks an important factor in how "anti-elite" sentiment has been channeled over the past quarter century: through "anti-elitist" tycoons. Trump is only the latest instance. Celebrity, bully-boy charisma and deep pockets have established him as a force in politics, despite an almost policy-free message that seems to take belligerence as an ideological stance. Before that, there was the more discrete largess of the Koch brothers (among others) in funding the Tea Party, and earlier still, Ross Perot's 1992 presidential campaign, with its folksy infomercials and simple pie charts, which drew almost a fifth of the popular vote. In short, "revolt against a distant, high-handed elite" may be written into the source code of American politics; the billionaires have the incentives and the means to keep trying to hack it.

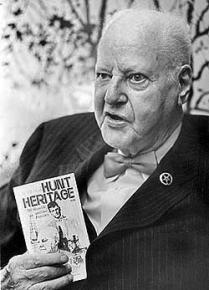

IF ANYTHING, even Perot was a latecomer. In the opening pages of Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy (University of Chicago Press), Edward H. Miller takes note of a name that's largely faded from the public memory: H.L. Hunt, the Texas oilman. Hunt was probably the single richest individual in the world when he died in 1974. He published a mountain of what he deemed "patriotic" literature and also funded a widely syndicated radio program called Life Line. All of it furthered Hunt's tireless crusade against liberalism, humanism, racial integration, socialized medicine, hippies, the New Deal, the United Nations and sundry other aspects of the International Communist Conspiracy, broadly defined. ("Nut country" is how John F. Kennedy described Dallas to the first lady a few hours before he was killed.)

Hunt's output was still in circulation when I grew up in Texas a few years after his death, and reading it has meant no end of déjà vu in the meantime: the terrible ideas of today are usually just the terrible ideas of yesterday, polished with a few updated topical references. Miller, an assistant teaching professor of history at Northeastern University Global, reconstructs the context and the mood that made Dallas a hub of far-right political activism between the decline of Joseph McCarthy and the rise of Barry Goldwater--a city with 700 members of the John Birch Society. A major newspaper, The Dallas Morning News, helped spur the sales of a book called God, the Original Segregationist by running excerpts. Cold War anti-Communism mutated into a belief that the United States and the Soviet Union were in the process of being merged under the direction of the United Nations, in the course of which all reference to God would be outlawed. John F. Kennedy was riding roughshod over American liberties, bypassing Congress and establishing a totalitarian dictatorship in which, as H.L. Hunt warned, there would be "no West Point, no Annapolis, no private firearms--no defense!"

An almost Obama-like dictatorship, then. Needless to say, these beliefs and attitudes are still with us, even if many of the people who espoused them are not.

Miller identifies two tendencies or camps within right-wing political circles in Dallas during the late 1950s and early '60s. "Moderate conservatism" was closer to established Republican Party principles of free enterprise, unrelenting anti-Communism and the continuing need to halt and begin rolling back the changes brought by the New Deal. Meanwhile, "ultraconservatism" combined a sense of apocalyptic urgency with fear of all-pervasive subversion and conspiracy. A reader familiar with recent laments about the state of the Republican Party--that it was once a much broader tent, with room for even the occasional liberal--might well assume that Miller's moderate conservatives consisted of people who liked Ike, hated Castro and otherwise leaned a bit to the right wing of moderation, as opposed to ultraconservative extremism.

That assumption is understandable but largely wrong: Miller's moderates were much closer to his ultras than either was to, say, the Eisenhower who sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas. (Or as someone the author quotes puts it, the range of conservative opinion in Dallas was divided between those who wanted to impeach Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren and those who wanted to hang him.)

Where the difference between the moderates and the ultras ultimately combined to create something more durable and powerful than either of them could be separately was in opposition to the civil rights movement and their realignment of the segregationist wing of the Democratic Party. I'll come back to Miller's argument on this in a later column, once the primary season has progressed a bit. Suffice it to say that questions of realignment are looking a little antiquarian all the time.

First published at Inside Higher Ed.