Natural beauty or unnatural oppression?

tells the story of the National Park Service--and argues that we need to understand its unsavory history without abandoning the goal of conservation.

THIS YEAR marks the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the National Park Service (NPS).

The NPS today is widely viewed the way Ken Burns coined it in his six-part documentary: "America's Best Idea," But is it?

The NPS was no doubt a better idea than slavery, imperialism and the genocide of Indigenous people. But Burns's description glosses over the bloody and contradictory history of the park system, particularly its relationship to Native Americans.

As Alston Chase wrote in Playing God in Yellowstone:

Congress, in creating the park "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people," destroyed the livelihood of another people. From the beginning this sad fact was a skeleton in the closet of our park system, a past too embarrassing to contemplate, for it demonstrated that the heritage of our national park system and environmental movement rested not only on the lofty ideal of preservation, but also on exploitation.

THERE ARE many players in the complex story of the national park system: rich "do-gooder" conservationists such as John D. Rockefeller; ordinary environmentalists; American Indians, who were and still are often "in the way" of establishing parks; poor rural Blacks and whites in places like the Smoky Mountains; railroad companies; and, of course, the capitalist energy sector, always looking to suck every last drop of resources out of the earth.

Decades before any national park was ever established the painter and author George Catlin put forth a vision for them in his 1832 book North American Indians.

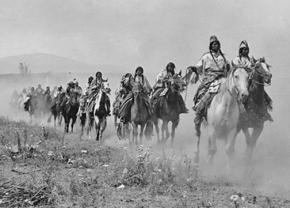

One imagines--by some great protecting policy of government...a magnificent park, where the world could see for ages to come, the native Indian in his classic attire, galloping his wild horse, with sinewy bow, and shield and lance, amid the fleeting herds of elk and buffalo.

As the first proponent for a national park, Catlin's vision was essentially a zoo for Native cultures--which would be replicated years later.

The first park was created in 1872 when President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Act of Dedication to create Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Five years later, Grant sent two small parties from Montana to explore the area and report back to the government.

At the same time, a band of Nez Perce Indians led by Chief Joseph was fleeing efforts by the U.S. Army to force them to join all other Indians in the West on reservations. As they were journeying toward Canada, Joseph's band ran into the exploratory parties, resulting in the death of two of the tourists visiting the new park.

The conflict with the Nez Perce--who were eventually captured by the U.S. Army just before reaching the Canadian border--was a sign of things to come in the relationship between American Indians and national parks.

ALTHOUGH YELLOWSTONE and many other parks were established early on, it wasn't until 1916 that Congress and President Woodrow Wilson created the NPS to oversee all the national parks.

The bill established the NPS "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

The early park advocates were almost all wealthy white men looking to preserve a slice of pristine nature from their own planet-destroying industries. Henry Mather, the first director of the NPS, made his money in the mining industry. John D. Rockefeller built an oil empire and then used some of his earnings to buy private land that he gave to the government to establish Acadia National Park in Maine and the Grand Tetons National Park in Wyoming.

The parks grew dramatically as they were advertised around the country. Railroad companies made sure their lines would go through the parks--and often owned the hotels and hospitality elements of various parks. Outside the parks, the railroad lines were the center of mining and clear-cutting of forestland for the timber industry.

The parks were supposed to represent America before Europeans arrived on this land mass--a vision that often did not include Native Americans. Natives were therefore cleared out of areas in which parks were established, making the creation of parks both a reflection of the "Manifest Destiny" ideology and a tool to carry it out.

Those Indians who remained in the parks were to be treated as part of the exotic wildlife or relics of the past without distinct personalities.

Glacier National Park was established over the objections of the Blackfeet Nation, who disputed NPS ownership. The Blackfeet lost all hunting and fishing rights in the park, but they were used as props for the tourist experience. In the 1920s, at the East Glacier Lodge, which was owned by the Great Northern Railroad, Blackfeet members were featured in a "Northern Plains Indian camp" in front of the hotel to "provide local color."

Horace Albright, the second director of the NPS, wrote in his 1928 book Oh Ranger that in national parks one could still find "real Indians, the kind that wear feathers, don war paint, make their clothes and moccasins of skins...The best place for the Dude to see the Indian in his natural state is in some of the national parks."

The mid-20th century saw the creation of Smoky Mountain National Park and Shenandoah National Park--both on Appalachian land where President Andrew Jackson's infamous removal of the Cherokee via the Trail of Tears had taken place a century earlier. Some of the poor descendants of the settlers who replaced the Cherokee found themselves being evicted by the same government, this time for the purpose of creating national parks.

ENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS were some of the leading proponents of national parks as valuable tools for environmental conservation, but for decades, these groups failed to understand the importance of linking their cause with Native American self-determination. On the contrary, many environmentalists argued that parkland needed to be "saved" from Natives who didn't know how to manage it.

In the mid-1970s, the Sierra Club supported NPS efforts to expand the Grand Canyon National Park, but came up against the Havasupai Tribe, some of whose Tribal Council members wanted to build a dam to help their nation get out of poverty.

The Sierra Club started a smear campaign against the Havasupai, calling them dupes of developers and using language such as "theft," "land grab" and "raid" to make their case--a true irony, considering the circumstances. The Havasupai ended up winning this battle when 185,000 acres of land was transferred from Park and Forest Service lands to the tribe--and the dam was never built.

Today, the NPS, like environmental justice groups, has better relationships with Indigenous nations. There are more indigenous people on the NPS staff, and there is more space for some nations to tell their story. But the agency still has a ways to go with training--and more importantly, it continues to oppose handing over parks to Indigenous nations that lay claim to some of these areas.

Badlands National Park in South Dakota is often cited as an example of the improved relationship between Native Americans and the NPS. Half of the park is in South Dakota and the other is on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

The part on the reservation is co-managed between the NPS and the Oglala Lakota Nation's Park and Recreation department. It's a great reform, but the NPS is still unwilling to allow the tribe to manage the park on its own.

Over time, the national parks--which were started as a refuge from capitalism in the minds of their founders--have been forced to become yet another revenue-producing entity, motivated more by generating tourist dollars than protecting the planet.

In the 1950s and '60s, the NPS launched Mission 66, a project to pave roads and improve park infrastructure to bring thousands of people to experience the parks via their cars, illustrating the contradictory nature of national parks in a capitalist society that always prioritizes profit over preservation.

The 100th anniversary of the NPS is an occasion to celebrate efforts to preserve and appreciate the natural beauty of the U.S. But it's also a moment to recognize the contradictions of national parks without abandoning the idea of preservation and conservation.

We need to fight for more democratic national parks that actually fight to save the earth and ensure Native American self-determination. It will take a social movement to push parks forward with justice at the core of their values.