A union that defied an era of retreat

reviews the history of a union that represented an alternative in the 1920s.

MEMBERS AND students of the labor movement have an excellent new book on a little studied chapter of left-wing history in Sharon McConnell-Sidorick's recently published volume on the hosiery workers of Philadelphia. Silk Stockings and Socialism offers fascinating insight into a corner of U.S. labor and radical history that has received far too little attention until now.

Leaning heavily on the methods of cultural history, the book delves into a world that in some regards seems to have existed a million years ago. And yet, with the timely revival and increased popularity of socialist politics in the U.S., readers will likely find more than a little that is fresh and relevant to our own time.

McConnell-Sidorick's history uncovers the radical history of garment and hosiery workers in the working-class immigrant neighborhood of Kensington in Philadelphia, which became a rich and nourishing ecosystem for radical, independent and socialist movements.

Home to the original leaders of the Knights of Labor in the 19th century, Kensington had become, by the 1920s, an epicenter of radical working-class politics in greater Philadelphia, leading to the rapid growth of the left-led American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers (AFFFHW).

The book draws on interviews with former union members, a wealth of archival material and oral histories collected in the 1930s by investigators from the University of Pennsylvania to paint a dynamic view of life in Kensington and the world that the hosiery workers fashioned as they struggled to achieve a measure of dignity and economic security for themselves and their families.

THE AFFFHW managed to grow during the 1920s, a decade known more as a period of labor retreat and defeat in the face of a brutal employer's offensive to roll back whatever gains workers and their unions had made during the First World War period.

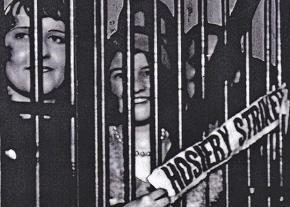

While other large employers across Philadelphia and the region were annihilating unions in their workplaces and instituting an "open shop" regime, the AFFFHW threw down the gauntlet against hosiery manufacturers and thoroughly beat them in two postwar strikes that established and consolidated union power in the hosiery shops of Kensington in 1919 and 1921.

Financed by the surging demand for luxurious silk stockings in the "Roaring Twenties," the consumer spending patterns of the Jazz Age seem to have created a niche market--something that the hosiery workers would use forcefully to their advantage to establish an impressive measure of union power.

Throughout the period of union growth, the small but militant AFFFHW sponsored an impressive array of labor, political and social activities that represent a high water mark for unions of the era. Conscious of the fleeting nature of their strike victories if not consolidated, the union attempted to build its strength across the industry, spending the rest of the decade in an inspiring "follow the shops" campaign to organize runaway hosiery manufacturers.

U.S. garment and textile manufacturers represent some of the earliest examples of capital flight in the 20th century--they consciously moved old operations or opened up new ones in far-flung corners of the country thought to be immune to unionization, from Durham, North Carolina to Kenosha, Wisconsin.

But AFFFHW organizers followed them wherever they went, signing up members, calling strikes and chartering new branches of the union.

And as the union grew, its organizing practices did as well, shifting from a more insular male-dominated organization of skilled hosiery knitters to embrace a semi-industrial model of embracing unskilled and semi-skilled workers that swept thousands of new embers, most of them young women, into the union's ranks.

By shifting to more of an industrial approach, the union gained far more bargaining power than larger ones, plus gained a creative and idealistic generation of young people who would leave their imprint on the union before the end of the decade.

A University of Pennsylvania study cited in the book found that more than 70 percent of the industry's workers during that time were under the age of 30, and 40 percent were under the age of 21, making it different from most other unions of the time.

WHAT WAS it about this union that allowed it to survive and thrive whiles others didn't?

McConnell-Sidorick argues that some of the key factors were its creation and reinforcement of a dense web of union-sponsored institutions, community connections and political initiatives that won the loyalty of its young members.

Strands of that web included union reading and study circles; social outings, dances and singing groups; scholarships for members to attend labor education institutions like the Brookwood Labor College; union-built affordable housing; organizing programs in which rank-and-file members became agitators for the union at nonunion shops during their lunch breaks; childcare provided at union meetings; early efforts at what the 1960s generation termed "consciousness raisings"; and support for local labor party initiatives and the left wing of the Socialist Party.

The union's political efforts seem particularly impressive in the face of much of the current labor movement's cynical insider opportunism, paired with an insistence on remaining a loyal ATM for the Democratic Party. McConnell-Sidorick describes the AFFFHW sponsorship of a Labor Party ticket in city elections in 1931:

The party adopted an impressive platform, similar to that of the Socialist Party, in preparation for a run in the 1931 primaries. Labor called not only for the socialization of utilities and transportation, but for unemployment insurance; an end to evictions and for the building of municipal housing; an income tax on the rich; and an end to discrimination on the basis of sex and race.

The local Labor Party ran members and officials of the AFFFHW for a full slate of candidates in every district of Philadelphia, but was knocked off the ballot on a technicality--but not before garnering support from thousands of union members and working-class voters.

In 1932, the local union endorsed the Socialist Party in national elections, with an SP member and key local labor movement collaborator named James Maurer running as the vice-presidential candidate on a ticket with Norman Thomas.

By the late 1930s, the union would play an outsized role locally, helping new unions form across Philadelphia and using sit-down strikes and mass picketing to bring many of the remaining nonunion hosiery shops to heel. As one of the Communist hosiery workers featured in the book remembered:

When I recall the events that took place at Fifth and Luzerne Streets on May 6, 1937, they intermingle with the recollections of what I have read over the years about the storming of the Bastille and the Winter Palace. The Apex [hosiery mill] strike was a thing apart, it was hardly a strike; it was an invasion."

The AFFFHW in Philadelphia also played a role in the formation of a new union at the Philco radio plant, which would become one of the key locals in the soon-to-be-chartered United Electrical workers union. The hosiery workers would go on to become one of the earliest and staunchest supporters of the CIO in Philadelphia.

AVID READERS will probably be left with more questions and an even keener interest in some of the points touched on in the book that definitely deserve more study. Among them:

Why exactly did the AFFFHW seem to avoid the brutal factional war between the Communist and Socialist Parties that wracked other garment unions during the 1920s--most notably the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU)?

What were the organizational and political lines of debate involved in the local's rising opposition to the national leadership of Emil Rieve, who followed the lead of his contemporaries David Dubinsky and Sidney Hillman in seeking partnership with the garment manufacturers in exchange for stabilizing the industry?

What was the impact of the split in the Socialist Party between left and right wings?

What role did the hosiery workers play in the developing CIO after its early years as it grew and bureaucratized?

These questions are beyond the scope of McConnell-Sidorick's book, but may inspire others to dig deeper into the history of the AFFFHW.

In any case, Silk Stockings and Socialism is a rich contribution to the historical literature on the period--and an inspiring read for any participant in the workers' movement today who seeks a better world by standing on the shoulders of those who came before us.