My voice was heard from death row

Stanley Howard was sentenced to Illinois’ death row in 1987 based on a confession tortured from him by Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge’s underlings. Held in an interrogation room for over 40 hours, Stanley was repeatedly punched and kicked, and had a typewriter bag put over his head to suffocate him.

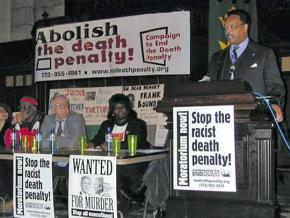

In prison, Stanley, along with other police torture victims, formed the Death Row 10 and reached out to the Campaign to End the Death Penalty (CEDP) for help. The CEDP agreed, and a deep bond developed as they worked together, from the inside and the outside, to try to win justice for these prisoners. CEDP members and other activists organized press conferences, protests and rallies, and Live from Death Row forums, where prisoners would speak to an audience via speakerphone. Stanley called in to many of these forums, and he was a columnist for the CEDP’s New Abolitionist newsletter.

As a result of the determined work of prisoners themselves, activists on the outside, lawyers and journalists, the death penalty in Illinois was exposed for its racism, unfairness and shocking errors. In 2003, Stanley was pardoned of the charge that landed him on death row by then-Gov. George Ryan as he commuted all death sentences. Unfortunately, Stanley remains in prison on another charge but hopes to be released soon. He has just finished a book called Tortured by Blue that is on its way to the printer.

, the former national director of the CEDP, interviewed Stanley about the years working in the CEDP and what lessons and reflections might be important today.

IN THE two decades that the Campaign to End the Death Penalty (CEDP) existed, what stood out to you as its accomplishments?

THE CEDP was established when executions in America were at a high point since the death penalty was reintroduced.

It was also when politicians were fighting with each other trying to prove who among them was tougher on crime. This fight led to the elimination of many safeguards and protections so that it would be easier to convict and quicker to execute.

Through its organizing skills and activism, the CEDP was able to help change the landscape of the criminal justice system, taking it from the unjust tough-on-crime era to a path where even the staunchest Republicans are calling for reforms.

The CEDP was part of the push that forced Illinois Gov. George Ryan to openly admit that the death penalty was “broken” and filled with errors. His admission led to the first moratorium on capital punishment, the clearing out of Illinois’ death row and the eventual abolition of the death penalty in the state.

IN WHAT ways was the CEDP different from other groups you encountered in organizing against the death penalty?

I BEGAN working with the CEDP in 1998 when its national director, Marlene Martin, responded to one of the many letters I sent out from my cell on death row.

I was seeking assistance on a new idea I had to form what we called “the Death Row 10” — a group of prisoners on death row who had all been convicted after being tortured by Chicago police under the command of Jon Burge. She agreed to help us in any way she could.

Some of the CEDP members, including Joan Parkin, Alice Kim, Noreen McNulty, Julien Ball, Marlene and others, were also members of the International Socialist Organization. And in my opinion, what made them different than other anti-death penalty groups was their willingness to confront the so-called powers that be.

They weren’t passive paper-pushers who sat in an office submissively until an execution was inevitable. They were proactive. They were hard-nosed activists who had no problem organizing our families and friends, or networking with other people and groups for rallies and protests.

And what I liked the most is they had no problem with face-to-face confrontations with police department officials, Chicago’s Mayor Richard M. Daley, or Cook County State’s Attorney Dick Devine, and later Anita Alvarez. No one was off-limits from their opposition.

The CEDP came around at the time when we needed someone to think outside of the box and take our fight to the street — to the people. And their grassroots organizing was our number-one fighting tool. It was the main weapon that kept politicians and public officials back-peddling and running for cover.

WHAT CONCLUSIONS did you draw about how we need to organize against the criminal justice system and racism?

I CAN understand why some groups feel the need to organize among themselves, with African Americas separate from whites and others. Their fears and suspicions are real, but it must not serve as the reason to isolate your group from organizing with like-minded people and groups.

Our fight to expose the Chicago police torture scandal, the death penalty, and the broken, corrupt, racist criminal justice system involved people of all races — the human family — networking and fighting as one.

That’s how people fought together to help abolish slavery and bring an end to Jim Crow, and that’s how they stood on the front lines with my blood family to save my life when I was about to be lynched on Illinois’ death row.

Our brothers and sisters who are carrying the torch and standing on the front lines today need to understand that in the era of Trump and Jeff Sessions, we need all hands on deck for battle. Nothing should divide our human family in the fight for political, social and economic justice — because divide is exactly what Trump is trying to do. We must stand and fight together.

I’ve been really motivated and inspired by those who are carrying the torch today. I’ve seen them standing and demanding justice for Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Laquan McDonald and so many others. And I can close my eyes and still hear all of them screaming as one: “Hands up, don’t shoot,” “I can’t breathe” and “16 shots and a cover-up.”

I saw a young white woman activist lose her life in Charlotteville, Virginia, standing up against white hatred. My days behind bars are soon coming to an end, and I will be marching and shouting in solidarity with you.

HOW DID you, as an individual, change, learn, grow and develop as a result of being involved with the CEDP?

WORKING WITH the CEDP and members of the ISO was a crash course in activism for me. They opened my eyes to a lot of things I didn’t know about or care about — causes that were bigger than my personal fight to save my life.

I saw people dying because they couldn’t afford medication or health insurance. I saw how poor folks are housed and educated, compared to those at the top of the food chain. I saw how top 1 Percent robs the bottom 99 Percent out of most of the world’s wealth without shame.

I saw million of children dying of starvation while only a few people together had hundreds of billions in wealth. I saw the injustices surrounding mass incarceration and how the school-to-prison pipeline worked. I saw the unjust and racist manner in which the death penalty was being used in this country.

And I saw how this rigged system was being controlled by the same two political parties that drive this country into the ground, while the rich get richer (and all the tax breaks) and the poor get poorer.

The CEDP gave me the opportunity to use my voice to speak out from my cell on death row.

I was given my own column, called “Keeping It Real,” in the CEDP’s newsletter The New Abolitionist. And I participated in many “Live from Death Row” events, where I was able to call in and speak to audiences around the country about the death penalty, my life on death row and the Chicago police torture scandal.

I loved being able to interact with the audience, where they were able to ask me questions — most had a hard time believing that cops were torturing suspects in Chicago to obtain so-called confessions.

I grew and changed so much that when George W. Bush kicked off the war in Iraq in 2003, right after I was released from death row based on innocence, I started a group called “Prisoners Against the War” while I was in Statesville prison.

Working with the military resisters in New York City and ISO members Thomas Barton and Alan Stalzer, prisoners were able to send letters to the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. We wanted them to know that we supported them 100 percent, but were against the war and wanted them to come home safely.

I hated that warmongers were able to send our brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers, onto battlefields to kill each other when we’re all part of the same human family.

I’ve been forever changed because I was taught that I have an obligation and duty to get in the fight. There will be no standing on the sidelines and hoping that things will get better — I had to get in the fight in some form or fashion to make it better.

Thanks for giving me this opportunity. I’ll see you all on the front lines real soon.