Ambition without principles

The "New Labour" leaders who ran Britain for more than a decade didn't have two principles to rub together, concludes Irish journalist and socialist .

THERE ARE some who sneer at Nelson McCausland, the Northern Ireland government minister, for believing that God made the world in six working days back in the summer of 4004 B.C.

But at least Nelson doesn't believe--as far as I know--that the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq have made Britain safer by encouraging young Muslims to look favorably on the role of the West in Muslim lands.

But that's what former New Labour Home Secretary Jacqui Smith believes. Or so she says.

Smith was on the radio on Sunday morning explaining that the government she was part of until sacked last year following stories to do with porn movies (rented by her husband) and second-home expenses (inadvertently claimed) had never really put a foot wrong on foreign policy.

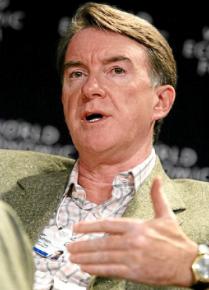

I listened to this as I turned the last few pages of Peter Mandelson's vanilla-scented autobiography The Third Man. Mandelson, a top official in the Labour Party governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, doesn't go so far as to suggest that the occupation of Muslim lands, or the no-nonsense tactics of "Our Boys in Basra," or the rendering of kidnap victims into the hands of torturers have turned potential recruits for al-Qaeda into applicants for the Territorial Army. But he sees no reason to look back in angst at the key decisions either.

Perhaps it says something about the loyalty of senior Labour figures to one another that two people who had something of a torrid time in government now have no serious criticisms to make of their colleagues' decisions.

On matters such as terrorism, invasions, assassinations, advances in thumbscrew technology, etc., Mandelson is all "comme ci, comme ça."

But when it's whether Tony should have told Gordon to eff off when he startled whinging about wanting to be prime minister right now, he spits nails in frustration at the stupidity of the pair of them. It is personal ambition and political maneuver which engages Mandelson's serious side.

THE THINGS he makes light of, however, continue to weigh heavily on minds elsewhere.

In the week of publication of the Mandelson book and Smith's reemergence from post-election purdah--the electors of Reddich gave her the heave-ho in May--the woman who headed the spy agency MI5 from October 2002 to April 2007, Eliza Manningham-Buller, told the Iraq inquiry under John Chilcot that, in essence, everything the antiwar movement had warned of prior to the invasion in 2003 had been spot on. Manningham-Buller recalled that she'd told the government prior to March 2003 that invading Iraq could enrage young British Muslims to the extent that some would turn to terrorism.

But Jacqui Smith believed, nevertheless, that the exact opposite would happen--and believes now that this, indeed, is how things have worked out.

The mind boggles. But it shouldn't. Listening to Smith and Mandelson in stereo, as it were, what became unsettlingly clear is that these people don't really believe in anything.

Mandelson provides an account of bitter and vicious faction-fighting which would do credit to a convention of cutthroats. Blair, he reports, saw Brown as "mad," "bad," "dangerous," "hair-raisingly difficult to work with" and "beyond redemption." And this knife-fight relationship could be vital in determining policy on areas of fundamental importance.

Former New Labour ministers who have commented on Mandelson's memoirs have likewise focused on who was skulking around Westminster waiting for the most advantageous moment to plunge the dagger into an old friend's back--rather than on, for example, the decision to bin the advice of everyone from the boss of MI5 to 2 million citizens tramping the streets and rush to war regardless.

There is nothing in Mandelson's book to suggest that there was a single serious discussion of political ideas among the leaders of New Labour between the moment they managed to get their feet under the cabinet table to the day they were dumped out of office.

New Labour was an empty vessel into which it was possible to pour any old ideology which seemed to serve ambition at the time.

But praise where it is due. Mandelson did choose the perfect title for his tome. In Carol Reed's 1949 film classic, The Third Man, Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles, is a cunning operator with no sense of morality, who betrays his friends and ends up shot in the back by a journalist as he sloshes and scrabbles in vain efforts to haul himself out of the sewer.

Nelson McCausland is a shining example of intellectual rigor, common sense and progressive political ideas when compared with this lot.

First published in the Belfast Telegraph.