Exposing a topsy-turvy world

is co-author, with the late Howard Zinn, of Voices of a People's History of the United States, a companion volume to Zinn's classic People's History of the United States. On the 90th birthday of the people's historian, he recalls Zinn's lasting message--that the only hope for accomplishing meaningful change is to work for it.

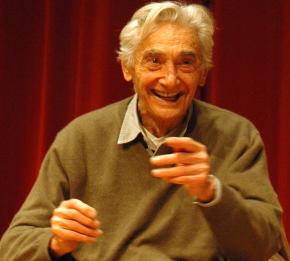

HOWARD ZINN would have turned 90 on August 24 if his seemingly boundless energy and youthfulness had not been cut short in January 2010.

Toward the end of his life, when a New York Times reporter called him with the morbid task of interviewing him in preparation for his future obituary, he asked him, "What's your deadline?" Howard never missed an opportunity to add levity, a sense of humanity, to the often over-serious and sterile culture of the left.

Going through Howard's archives recently, gathering some of his talks for a book, I found early speeches of Howard's I had never listened to before. The speeches, going back to 1963, showed Howard's sharp political acumen, his clarity, his ability to speak the language of his audience in a way that crystallized their passions and ideals.

But they also revealed something I had not quite expected. Here in 1963, speaking in Atlanta to activists of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a very serious gathering, was Howard joking with his audience about ending his talk short because he was hungry.

I had thought that maybe Howard had probably grown into his ease with an audience, his dry wit. But he was clearly a natural from the beginning. How else would someone only 26 years old, as he was in 1948, be asked to introduce Henry Wallace at a presidential campaign event in Brooklyn? And how else could he sustain his remarkable optimism over all the years of setbacks and challenges he encountered?

It's worth remembering that A People's History of the United States first came out in 1980 as a tide of reaction was seeking to bury the social movements that inspired Howard's book and which he saw as the hope for the future. It could have seemed a hopeless venture in that political environment to seek to change the way the U.S. understands and teaches its history, and yet he achieved precisely that.

NOT SURPRISINGLY, there has been a backlash against Howard's impact on popular culture and on a younger generation whose teachers have found ways to bring into their classrooms A People's History of the United States, as well as the book I had the privilege to edit with Howard, Voices of a People's History of the United States.

There are historians who want to police the boundaries of their discipline to say Howard strayed too far into engagement with the world. There are liberals threatened by his political independence and desire to see more fundamental change than can be imagined within the ever-narrowing horizons provided by the Democratic Party. And there are always people who want us to know that things are "more complicated," by which they mean really, "things aren't really so bad."

Howard challenged these ideas in a terrific speech he gave in 1970:

If you don't think, if you just listen to TV and read scholarly things, you actually begin to think that things are not so bad, or that just little things are wrong. But you have to get a little detached, and then come back and look at the world, and you are horrified. So we have to start from that supposition--that things are really topsy-turvy.

Howard had that rare ability to step back and help us understand our topsy-turvy world primarily because he approached politics and history from the standpoint of someone who thought it was possible to turn our world right side up--to put people before profit, the environment before the interests of mining companies.

As strange as it is to say of someone who was 87, Howard's passing was a shock. All of us who knew him and worked with him were usually racing to catch up with him, even as he became more frail and had difficulty walking.

While working on our film The People Speak, Howard would spend full days in the editing room of our post-production house, working to craft every frame and word. He was not content to let others do the work, to rest on his laurels.

To the end, he was committed to the belief that the only hope for meaningful change is to work for it--and that there is no more meaningful life than one spent working alongside others for a better world.

That is why you will find Howard's ideas and books at any Occupy encampment that is allowed to spring up, why every week on the subway I see some new person engrossed in reading A People's History, why Howard's legacy is more relevant than ever in our age of ever-diminishing expectations.

First published at Alternet.