What made Mumia a revolutionary?

reviews a new documentary on the life of Mumia Abu-Jamal--one that focuses on the period before he became a voice for justice from prison.

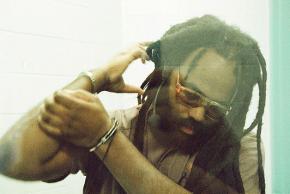

MANY ON the left are familiar with the struggle for justice of political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal, wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in 1982 for the killing of a Philadelphia police officer. The death sentence was later overturned, but Mumia's appeals against the conviction have been turned down.

Fewer are aware of Mumia's own politicization, his evolution and influence as a revolutionary writer and thinker--or, in the words of radical scholar and activist Angela Davis, "the most eloquent and most powerful opponent of the death penalty in the world...the 21st-century Frederick Douglass."

A new documentary, Mumia: Long Distance Revolutionary, gives us a previously unseen glimpse of the world's best-known prisoner in an immensely powerful narrative of his life and works. Commentary from dozens of prominent figures such as Alice Walker, Cornel West, Dick Gregory, Michelle Alexander and Dave Zirin are woven with Mumia's own words on racism, repression and struggle.

The film's most important contribution is the deeply felt impact of those words and insights. As the late historian Manning Marable describes:

The voice of Black journalism in the struggle for the liberation of African American people has always proved to be decisive throughout Black history. When you listen to Mumia Abu-Jamal you hear the echoes of David Walker, Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Dubois, Paul Robeson and the sisters and brothers who kept the faith with struggle, who kept the faith with resistance.

THE FILM paints a more detailed biographical picture of Mumia than past documentaries, situating his family history in the early 20th century Great Migration of African Americans from the South.

Vittoria spends some time outlining Mumia's radicalization in the 1960s and the impact of the Black revolutionary struggle, relating, for example, Mumia's early experience of police brutality at a 1968 protest against a campaign appearance by George Wallace, the racist candidate for president. Mumia describes the confrontation:

I remember being pummeled and being beaten to the ground, and I remember looking around, and I saw a pant leg, and it was blue and had a stripe on it, so it told me this was a cop. So doing what I was taught to do all my life, I said, "Yo, help, police!" and I remember the guy walking over very briskly and his foot going back and kicking me in the face. And I've always said thank you to that cop because he kicked me straight into the Black Panther Party.

Mumia went on the become the Lieutenant of Information of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party at the age of 15, irrevocably shaped by the global struggles of the era.

As writer Tariq Ali describes onscreen, the violence of the Vietnam War had a profound impact on the understanding for millions of the nature of the system as a whole. Imperialism abroad and repression at home led many to conclude, as Mumia puts it, that "America is a wholesale terrorist."

In the 1970s, Mumia began to build a profile as a journalist, working for local radio and later National Public Radio, earning citations and awards for his work. Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo and the Philadelphia police department unleashed vicious brutality on African Americans, and the repression meted out against the Black Panther Party and later against the MOVE movement, featured prominently in Mumia's writing.

By December 1981, when a moonlighting Mumia pulled his cab over to help his brother fend off police, Mumia's vocal criticism of law enforcement was well-known.

The film touches relatively briefly on the facts of Mumia's arrest, trial and conviction, highlighting the overt racism of the police and the courts, and how they railroaded an innocent man onto death row. His trial was riddled with judicial misconduct, from the illegal removal of Black jurors to coerced confessions, contradictory physical evidence, outright lies on the part of the police, and the suppression of Mumia's rights in the courtroom.

The lack of a fair trial has been widely condemned, including by Amnesty International, which in 2000 "concluded that the proceedings used to convict and sentence Mumia Abu-Jamal to death were in violation of minimum international standards that govern fair trial procedures and the use of the death penalty...[T]he interests of justice would best be served by the granting of a new trial."

In the face of this overwhelming miscarriage of justice, advocates and activists built what grew to be an international struggle in support of Mumia, depicted in the film in several scenes of protests from the streets of Philadelphia to Paris and Berlin.

VITTORIA PAINTS a picture of the harsh realities of mass incarceration through dramatizations of Mumia's own existence behind the walls scattered throughout the film.

"The audience deserves to know what life is like in solitary confinement for almost 30 years," the director said in an interview. "Building the cell became an all-important element. The trick is to use it as connective tissue, not as a way to drive the narrative, but as a way to allow the audience inside this man's hell. Quick shots, darkly lit, glimpses of this writer's claustrophobic concrete wall existence."

Amid these brutal conditions, Mumia becomes a prolific writer, commentator, artist and jailhouse lawyer. As Alice Walker remarks onscreen, "My sense of Mumia is that he is working almost all the time. I mean, he must work as much as I do, and I work a lot."

From behind bars, Mumia continued his work as a journalist, with regular radio broadcasts and the publication of six books and hundreds of columns and articles. His first book, in 1995, Live From Death Row, generated national attention for his case while inspiring a new generation of activists radicalized by the "voice of the voiceless."

Above all, as the film makes clear, Mumia lends us a vision of resistance and its urgency today. From the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to mass incarceration, from Hurricane Katrina to the Egyptian Revolution, Mumia, as Educators for Mumia's Mark Taylor puts it, "takes one to the heart of the struggle."

The role of oppression, empire and the U.S.'s two-party system in furthering inequality lie at the center of his analyses, along with those on the front lines of the fights against them. Mumia's writings have held up these fighters--both those well-known to many and those who Mumia introduces to us for the first time, including those imprisoned alongside him.

In the meantime, Mumia continues the fight for his own case. Over the course of decades, appeals courts denied his claims until 2001, when a federal court overturned his sentence, but not his conviction. The authorities, however, refused to move Mumia from death row, extending his torture for another decade until, finally, in late 2011, the Philadelphia District Attorney gave up pursuit of a death sentence.

Mumia was eventually transferred to general population, when for the first time since his conviction, he was able to have contact visits with his family and supporters.

Mumia: Long Distance Revolutionary is a remarkable and necessary film. His struggle is far from over, and Mumia and supporters are gearing up for the next phase in the battle for his freedom. Activists are mobilizing on April 24 in Philadelphia to commemorate his 59th birthday, and the film is a crucial vehicle for building the campaign for the 24th and beyond.

Other movies such as Justice on Trial and In Prison My Whole Life will better arm those new to the case with the background and details of his arrest and conviction, as well as useful books such as The Framing of Mumia Abu-Jamal by J. Patrick O'Connor.

That said, Long Distance Revolutionary is an invaluable and moving portrayal of Mumia's contribution to the ideas that inform our struggle for a better world and, as Alice Walker puts it, the ability "to maintain one's humanity in the face of injustice." For these reasons, Mumia inspires activists worldwide to move into action on many fronts. With a looming fight to win his freedom, this film couldn't come at a better time.