Toward an anti-racist practice

The question of racism and how to fight it is central for any socialist interested in fighting for a better world--especially socialists in the U.S., where racism is woven into the fabric of society. The history of the Workers Party in the 1920s--the forerunner of the Communist Party--offers some important lessons about confronting racism and colonialism that can still inform our organizing today. In the first article of a three-part series, chronicles the history of how these "Bolsheviks in America" addressed racial inequality.

IN THE wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution, the Workers Party--as the Communist Party in the U.S. was known during the mid-1920s--initiated a set of anti-racist and internationalist policies and practices aimed at fighting for African American equality at home and opposing U.S. intervention abroad. These actions marked a breakthrough in the socialist movement, ending a long period of relative indifference to the fight against racism.

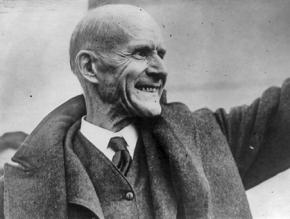

There had always been a section of the American socialist movement that was militantly anti-racist, exemplified by the Socialist Party's Eugene V. Debs and the Industrial Workers of the World. However, even at their best, these revolutionaries failed to theorize the link between their practical anti-racism and their militant class politics.

And if many socialists repeated the Communist Manifesto's famous slogan "Workers of the World Unite" by the late 19th century, defense of the working class in the U.S. was all too often paired with nativist sentiments and support for immigration controls, especially targeting Asian and Latin American immigrants.

The Russian Bolsheviks’ theory and practice of confronting national oppression, which only became widely known to socialists in the U.S. after the Russian Revolution, stood in sharp contrast to U.S. socialists' muddled record, and it quickly become a dividing line between the reformist and revolutionary wings of the movement.

This article will review the deficiencies of American socialism's attitude toward racism, the great transformation it underwent when confronted with the Russian alternative, and how the Workers Party applied its new theory in practical campaigns to challenge both anti-Black racism and the closely linked phenomena of U.S. colonialism and anti-immigrant bigotry.

There was nothing automatic about this development. It had to be fought out, but fought out it was. The revolutionizing of the American socialism movement in the 1920s changed the way that generations of Black and white revolutionaries understood the relation between socialism and Black liberation, thus forming one of the most important, and least recognized, chapters in what Howard Zinn famously called the People's History of the United States.

In this three-part series, Todd Chretien uncovers the early history of the U.S. Communist Party and its efforts to build a radical struggle against racism.The CP and the anti-racist fight

WHITE REVOLUTIONARIES played a prominent role in the abolitionist movement, and a cadre of socialists fought in the Civil War to end slavery, including Karl Marx's close friend and collaborator Joseph Weydemeyer. In fact, the International Workingmen's Association under Marx's leadership, explicitly linked the potential for working-class liberation to the necessity of anti-racist struggle. In 1865, writing to Abraham Lincoln upon his re-election on behalf of the International, Marx explained:

The workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American Antislavery War will do for the working classes.

Just two years later, Marx argued in his most famous work Capital:

In the United States of America, every independent workers' movement was paralyzed as long as slavery disfigured part of the republic. Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the Black it is branded.

Yet, Marx's insistence on an anti-racist socialism all too often succumb to indifference and worse during the very years when Jim Crow segregation and Klan terror reached their apogee.

In order to assess changes in the Workers Party's approach to racism and colonialism in the mid-1920s, we must review its most important precursors, the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). European immigrants and native-born white workers and intellectuals made up the vast majority of the socialist movement that emerged after the U.S. Civil War. There were notable exceptions, but African Americans, Latinos and Asians rarely joined the various socialist groups.

Jim Crow and the relatively small Black population in the Northern industrial cities, where socialist ideas took root most often, partially explained this reality. However, the socialist movement's failure to recruit African American workers in any substantial number also stemmed from its acquiescence to racism and its view of racial oppression as simply a form of class exploitation.

The Socialist Party, founded in 1901 by a coalition of utopian socialists, radical trade unionists and small Marxist groups, included within its ranks both segregationists and principled anti-racists.

Victor Berger, one of the Socialist Party's most conservative leaders and its most successful politician, serving two terms in Congress, represented predominantly German immigrant workers from Milwaukee, Wis. Berger spoke for a wing of the party that was openly hostile to African Americans and workers in nations under U.S. or European colonial rule, writing "There can be no doubt that the negroes and mulattoes constitute a lower race."

This sort of bigotry obviously held no appeal for Black workers, but even Berger's socialist opponents on this question tended to reduce racism to mere mechanical expression of class exploitation. Eugene V. Debs, the Socialist Party's left-wing champion and four-time presidential candidate, personally opposed Jim Crow and refused to speak to segregated meetings. Yet Debs himself argued in 1903 that the socialists "have nothing special to offer the Negro, and we cannot make separate appeals to all the races."

Debs' thinking, for both better and worse, carried over into the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Founded in 1905, the Wobblies, as they were popularly known, brought together elements from the leftwing of the Socialist Party, radical trade unionists from the Western Federation of Miners and a small group of Marxists in the Socialist Labor Party. The Wobblies steered away from what they called "politics" (a reaction against what they perceived as the Socialist Party's attempt to court moderate voters), usually focusing on organizing on the job as opposed to broader community issue-based campaigns.

Although the IWW did organize Black workers in certain important instances, it mirrored Debs' position in that it had nothing "special" to offer African Americans in terms of systematically campaigning against lynching or racism in housing, education, transportation or the courts.

A MINORITY of Socialist Party members did prioritize anti-lynching and Black civil rights. Mary White Ovington and William English Walling worked with W.E.B. Du Bois to found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909, and DuBois himself briefly joined party of a brief stint in 1912. Paradoxically, the socialists who gravitated toward the NAACP tended to hail from the reform wing of the Socialist Party and had very little in common with the militants from the IWW.

There were some exceptions such as Rose Pastor Stokes who supported both the NAACP and the IWW. However, in general, the three-way split between open segregationists like Berger, practical anti-racist working-class revolutionaries like Debs, and the moderate socialists who advocated for civil rights legal reforms did little to cement socialism and anti-racism in the popular imagination.

The October Revolution in 1917 in Russia lit up the socialist movement all across the world like a lighting bolt, likewise provoking splits and realignments in the U.S. in both the Socialist Party and the IWW. By 1919, a new communist movement emerged from the smoke. Battered by vicious state repression and bruised by ideological battles, the movement initially splintered into rival organizations, the two most prominent being the Communist Party of America and the Communist Labor Party.

This is not the place for an exhaustive history of this period, but for the purposes of the topic at hand, neither of main communist factions initially challenged Debs' position on racism. As ex-Wobbly and early Communist leader James P. Cannon wrote many years later,

the American communists in the early twenties, like all other radical organizations of that and earlier times, had nothing to start with on the Negro question but an inadequate theory, a false or indifferent attitude and the adherence of a few individual Negroes of radical or revolutionary bent.

Two developments began to change the Communists' theory and attitude. First, by 1919 it became clear that the Russian Bolsheviks' most prominent spokesman, Vladimir Lenin, placed a tremendous emphasis on what he called the national question.

The Russian Tsar had ruled over a vast empire, comprised of dozens of oppressed nationalities, with a multitude of languages, religions, and cultures. Just over half of the Tsar's subjects were ethnically Russian, yet all were governed by a Russian aristocracy that promoted what Lenin called Great Russian chauvinism, a sort of racism or national supremacy.

It enforced this ideology by means of legal prejudice and extra-judicial violence. The Bolsheviks demanded that revolutionaries who happened to be from an "oppressor nation" (or racial group) go out of their way to combat prejudice and violence against members of oppressed nations or racial groups.

THE BOLSHEVIKS' approach began to influence leading American Communists' thinking in earnest by the 1920 Second Congress of the Communist International. The Moscow-based Comintern, as it was commonly referred to, was a coalition of revolutionary parties that had supported the Russian Revolution and had broken away from their moderate socialist counterparts forming separate Communist parties.

Lenin, speaking at a session dedicated to the need for Communists to oppose colonialism and national oppression, declared, "What is the most important, the fundamental idea of our Theses? It is the difference between the oppressed and the oppressor nations." Indian Marxist M.N. Roy then spoke, asserting the centrality of establishing "mutual relations between the Communist International and the revolutionary movement in the politically oppressed countries...like India and China."

John Reed, renowned journalist and founding member of the Communist Labor Party, then stood before the International to address the situation facing African Americans. While familiar with the broad strokes of Black history, Reed was no expert and his report reads awkwardly at times. Yet, his demand that "Communists must not stand aloof from the Negro movement which demands their social and political equality" marks one of the first definitive steps by a leading white American Communist to supersede Debs' "nothing special" formulation.

Second, just as white Communists struggled to come to grips with the Bolsheviks' emphasis on racial and national oppression, a small group of African American revolutionaries gravitated toward the Russian Revolution and its anti-colonial implications.

Dedicated to fighting racism in the U.S. and colonialism overseas, West Indian-born Cyril Briggs and a small core of Black activists founded the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) during the First World War. Briggs first entered an alliance with the Communist Party of America in 1919 (the rival to John Reed's Communist Labor Party) based on his enthusiasm for the Communist International's anti-colonial policies, joining a handful of other Blacks, including Surinam-born Otto Huiswoud, a founding member of the Communist Party of America, and the poet Claude McKay, a Communist sympathizer and co-editor of the left-wing journal the Liberator.

Although unable to fulfill their initial hopes of recruiting large numbers of Blacks into the Party, Briggs and Huiswoud did help the Communists take the first difficult steps toward relating to important African American organizations. These efforts crystallized in terms of stated policy in 1922 when McKay and Huiswoud helped draft the Comintern's resolution on "The Black Question," calling on the American Communists to "fight for the racial equality of Blacks and whites, for equal wages and equal social and political rights."

This change at the level of theory has to be emphasized as it stands in sharp contrast to the theoretical positions of even the best practical anti-racists like Debs. However, a snapshot of the Workers Party itself and the American political conditions in the mid-1920s only goes to show the challenges the Communists confronted in putting their new racial policies into practice.

After several years of government repression and internal division between 1919 and 1922, various Communist organizations united into one group, called the Workers Party. In January 1924, the party launched the Daily Worker, published in Chicago until early 1927 when it moved to New York, featuring especially extensive reporting from New York, Detroit, Cleveland, San Francisco, Boston, Minneapolis and other industrial hubs.

The paper reached an estimated 17,000 readers each day, implying a larger regular readership of perhaps twice the average party membership of 12,000 for the years 1924 and 1927. During those same years, the Workers Party published another two dozen weekly or monthly regional, foreign language or industry-specific journals, including a daily Yiddish newspaper. Thus, while a large majority of their members were ethnic European immigrant male workers, the regular readership of Party publications extended considerably beyond this base, reaching around 100,000 people on a regular basis.

By no means a mass party, the Workers Party could boast far greater organizational coherence and human resources than any challenger on the radical left. One indication of their organized strength surfaced at memorial meetings organized in dozens of cities in early February marking Lenin's death on January 21, 1924. In New York, some 25,000 attended the event at Madison Square Garden, while thousands more attended meetings in Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Cleveland, Kansas City and elsewhere.

The party remained an outsider to the Black freedom and anti-lynching movements, but it does go to show that if the party made a priority of becoming a factor among African American activists and immigrant groups, it had a considerable capacity to do so. Besides its sheer size and the Comintern-inspired change in its attitude toward fighting oppression, the party had recruited, and was developing, a talented group of writers and activists, both Black and white, who were capable of translating theory into practice.