Anti-racist internationalism

In the last installment of a three-part series on the history of the Workers Party--the forerunner of the Communist Party--and its anti-racist organizing in the 1920s, discusses the party's opposition to U.S. intervention and occupation abroad. Click here to start reading the series from the beginning.

WHILE THE Workers Party began to campaign against racism targeting African Americans between 1924 and 1927, it simultaneously organized sustained opposition to U.S. intervention abroad, especially in Latin America and Asia. These actions emerged from the Workers Party's view that the socialist revolution they advocated in the U.S. was intimately linked, even dependent upon, successful revolutions by workers in nations colonized or occupied by the U.S.

Similarly with respect to the communists' opposition to domestic racism, the Workers Party's anti-colonialism originated in the political practice of the Bolshevik Party. After an aborted communist uprising in Germany in 1923, the Russian leadership of the Comintern began to look beyond Western Europe for potential allies. If revolutionary potential in Western Europe had sustained the Bolsheviks' hopes between 1917 and 1924, thereafter, growing anti-colonial protests, especially in China, took center stage.

This shift to the East emerged on the front pages of the Daily Worker and would become a major focus of activity and organization for the Workers Party, especially between 1925 and 1927. The role this anti-colonial agitation played in developing a sense of anti-racist internationalism among U.S. Communists is particularly revealing.

In the first edition of the Daily Worker on January 13, 1924, party secretary Charles E. Ruthenberg reviewed the state of the Workers Party, noting that the Communist International "had criticized the Workers Party on one point; that is, that it had not carried out a sufficiently aggressive campaign against American Imperialism." In response, Ruthenberg committed the party to "launch a nationwide campaign against American imperialism in the West Indies, Central America, South America and in the Philippines" with special emphasis on the communists support "for the independence of the Philippines."

As was the case with opposing domestic racism, a series of articles and editorials in the Daily Worker led the way. In January 1924, communist intellectual Bertram Wolfe wrote the first of many pieces for the Daily Worker analyzing the Mexican labor movement and U.S. economic and diplomatic pressure on the post-revolutionary Mexican state. Dozens of articles over the next three years criticized U.S. military intervention in Nicaragua and Haiti, the conditions facing workers in the Panama Canal Zone, the labor movement in Cuba, and the conservative role played by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) south of the border.

Beyond simply reporting on the struggles conducted by Latin American workers, the Daily Worker asked its readers to identify with them as partners facing a common enemy. In the U.S., argued the editors, "Workers and farmers are blind to their own interests if they join in the profit struggle to 'protect the lives and property' of American dollars invested in Nicaragua."

OF ALL the colonial issues the Workers Party addressed, it most systematically campaigned around the developing Chinese Revolution between 1924 and 1927. The Daily Worker printed hundreds of articles during this period and there were whole weeks when coverage of the Chinese National and Communist Parties were featured prominently on the front page, especially during the summer of 1925 and the spring of 1927.

In this three-part series, Todd Chretien uncovers the early history of the U.S. Communist Party and its efforts to build a radical struggle against racism.The CP and the anti-racist fight

A typical headline in March 1925 read, "Workers (Communist) Party Urges Need of Cooperation Between American and Chinese Masses." The Daily Worker editors presented a heroic image of the Chinese working class to the party members and to their wider readership, typified in a cartoon in a special May Day 1927 issue titled, "Young China--Armed and Defiant." In it, a young Chinese worker holds a rifle in one hand and a red flag in the other.

Although this image might well be criticized for drawing a stylized understanding of the complexity of the Chinese working-class movement, the point here is to consider its impact on rank-and-file communists and their sympathizers in the U.S. At the time, anti-Chinese bigotry ran deep in the American working class, and Chinese workers often faced exclusion, discrimination and worse, especially on the West Coast.

Beginning in July 1925, the Workers Party began to mobilize its membership in cities across the U.S. to support the Chinese Revolution. In New York City, the local party worked alongside members of the Chinese Nationalist Party--or the Kuo Min Tang (KMT) as it was denoted in the press of the era--to organize five outdoor soapbox meetings. Fifty Communist speakers fanned out to strategic locations, including Union Square, 110th Street and Fifth Avenue in Harlem and Brownsville, Brooklyn, addressing workers during shift changes at shops and factories.

The article reporting this effort claimed that "[t]ens of thousands of workers...stopped to listen to communist speakers and to speak to the Kuo Min Tang, the Chinese People's Party." The Daily Worker may have exaggerated this enthusiasm, but it did note that at "the Union Square meeting there were a good many Chinese listeners." In the following days, the Workers Party attempted to duplicate its efforts in a number of other cities.

In Minneapolis, the Daily Worker reported an audience of 800 under the banner of "Hands Off China!" A leading local communist explained the "causes of the social explosion now convulsing China" and then a "Chinese student and member of the Kuo Min Tang" addressed the meeting. In Akron, Ohio, the Trade Union Education League, a caucus of radical trade union activists closely affiliated to the party, "held a successful picnic as an anti-imperialist demonstration, pledging itself to 'Hands Off China!'"

In Cleveland, Ohio, the Daily Worker recounted one of the most successful mass meetings, claiming some 1,500, including a sizeable number of African Americans, in attendance. "The secretary of the Cleveland branch of the Kuo Min Tang, Brother Hong, then mounted the rostrum. He was greeted by thunderous applause." The report asserted that he was loudly cheered when he asked, "What would you American workers do if you had to work 14 or 16 hours per day for low wages in a mill where your overseer was free to beat you?...You would fight, wouldn't you?" The report described this meeting as "the best that Cleveland has seen in a long time" and that a "large number of Chinese workers and many members of the Kuo Min Tang took part."

Oakland, Calif., communists conducted a similar effort to raise funds, collecting a total of $37.80 by holding what they dubbed "the first meeting ever held in this city at which Chinese, Japanese and American speakers spoke from the same platform." The Daily Worker reported, "Minister Alice Sum, president of the Unionist Guild and Cham Sut Yen, secretary of the Guild and the editor of Kung Sing, a Chinese labor paper presented the situation from the Chinese point of view." Next, the "solidarity of Japanese labor with their striking brothers of China was eloquently told by a young Japanese student, Kenotsu, and interpreted by Shiji Matsui of Berkeley."

Across the bay in San Francisco, communists supported an effort to put the Central Labor Council on record against U.S. intervention in China. The Daily Worker reported that "to everyone's surprise," the resolution presented by "the workers guild.., which is a Chinese working-class organization," easily passed the council. The resolution also garnered more than a dozen local union endorsements, presumably comprised predominantly of white, male workers, including painters, tailors, cap makers, cigar makers, carpenters, retail clerks and many others. If modest, these efforts are nonetheless significant given white California labor's history of anti-Chinese exclusion.

At this stage, the party, following the analysis put forward by the Comintern leadership, placed its hopes in the revival of the global revolutionary movement on the unity between the Nationalist Party and the Communist Party of China. A March 22, 1927, Daily Worker editorial predicted that "the fall of Shanghai to the People's Army...put on the order of the business of the Chinese Communist Party, the trade unions, the left wing of the People's Party and the peasant organizations, the establishment of the Chinese Soviet Republic."

The Daily Worker editors' predictions proved catastrophically flawed, as Nationalist strongman Chiang Kai-shek turned on the Chinese Communists in a coup on April 12, 1927, executing thousands of party members and supporters. The Daily Worker printed gruesome photos on page one of the summary executions of scores of Chinese Communists, noting that "American and British troops look exultingly on."

As noted above, the special May Day Daily Worker edition printed the "Young China" cartoon, stressing the continued identification with what the American Communists perceived to be their revolutionary comrades in arms who had been betrayed by the Chinese Nationalists in alliance with the U.S. government. The Workers Party acted on this belief, organizing a May 7 demonstration in New York's Union Square to show their continued support for the Chinese left.

With between 5,000 and 10,000 participants, the Daily Worker reported that the rally featured "Chinese, Japanese, Porto Rican [sic], Haitian, Italian, Negro and American speakers." The Communists portrayed the protest as a example of multiracial, international unity, noting that at "one time a Chinese, a Negro and a Japanese occupied the three [speakers] stands, at another time three women were speaking in the shifting kaleidoscope scene."

United Mine Workers left-wing leader Powers Hapgood, recently returned from a union-sponsored trip to China, shouted to the assembled throng that "one does not wonder why they are revolting under foreign control." The Workers Party kept up a steady supply of articles following the aftermath of the April coup, even if, by the second half of 1927, the decline of the Chinese Communists' fortunes diminished the party's emphasis on public demonstrations.

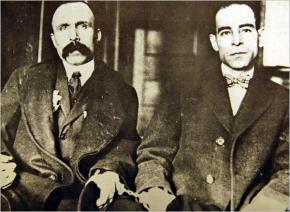

REELING FROM a string of setbacks, including Chiang's April coup in China, the defeat of the Passaic textile strike in 1927 and the sudden death of party secretary Charles Ruthenberg in March of that year, one potential bright spot appeared to be the growing global mobilization to save Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti from the electric chair. The immigrant Italian anarchists were convicted for a 1920 murder in Boston, but were widely believed to have been framed for their revolutionary political beliefs.

Throughout the spring of 1927 the Workers Party, which had campaigned for the two men since 1924, mobilized its membership and sympathizers to picket, petition, march and form emergency committees to plan a general strike to prevent the executions. While the Daily Worker continued to report on the aftermath of the April massacre in China and instances of lynching in the U.S., party journalists moved Sacco and Vanzetti to the front page throughout the summer of 1927.

On July 8, 1927, the Workers Party helped mobilize up to 25,000 in Union Square at a protest that ended with police attacks. The Daily Worker reported growing protests around the country and around the world as the execution date neared. Legal maneuvering and the threat of mass protests gained Sacco and Vanzetti a 10-day reprieve on August 11, setting the final showdown for the next execution date of August 22.

I will not recount the failed campaign to save Sacco and Vanzetti here. Suffice it to say that the Workers Party did everything in its power to stop the executions. Much of this activity was conducted under the banner of the International Labor Defense (ILD), established in 1925 by Workers Party leader and ex-Wobbly James P. Cannon after a discussion with legendary mine workers leader William "Big Bill" Haywood, then living in exile in Moscow.

The relevant aspect here is how the party understood the Sacco and Vanzetti case in relation to organizing against domestic racism and colonialism.

The July cover of Labor Defender featured a photo of Chinese workers surrounding a heavy machine gun, emblazed with the headline "Hands of China!" Inside, photos commemorated solidarity protests organized in Chicago outside the British consulate against foreign intervention in China. The photos featured banners written in Chinese characters proclaiming pro-union and anti-colonial slogans. The display is placed next to several photos from the interment ceremony of Ruthenberg's ashes in Moscow.

The issue featured articles analyzing the potential for a U.S. invasion of China and argued that American workers' "interests lie in support of the Chinese revolutionary movement, for it is fighting for a cause which is our own, the cause of victory against the imperialist master class." The article contended that "the American workers have a common cause with the courageous Chinese people" and, therefore, "must end the support of the American imperialists to the butchers of the Chinese trade union movement and the peasants' movement."

The Labor Defender editors plainly encouraged their readers to conceive of the working class united across national boundaries that explicitly included non-European workers as equal partners. They did this by juxtaposing photos of Chinese workers and white Chicago communists as well as alternating stories about Passaic strikers, the fight for Sacco and Vanzetti, and a feature article about China.

Finally, the editors profiled a story about Pablo Manlapit, a Filipino strike leader imprisoned in Hawaii, reporting that "[p]eople of other races have besides the Filipinos have expresses a desire to help in this case and they will find in this paper a willing agency for carrying out their wishes."

In the midst of the Sacco and Vanzetti campaign, when the Communists were making their maximum effort to enlist predominantly white AFL locals, they insisted on their belief that workers must conceive of these fights as intimately linked across racial and national lines. However, there is a glaring absence from the Labor Defender's portrayal of anti-racist, international solidarity.

The Workers Party made little attempt to specifically appeal to African American organizations or individuals in its campaign to defend Sacco and Vanzetti. The Daily Worker continued to report on instances of racist violence against African Americans throughout the summer of 1927, including a front-page article defending Black residents' right to self-defense against threats by white racists. Yet, I did not find any examples in either the Daily Worker or the Labor Defender of the Workers Party reporting on the participation of African American organizations or activists in the Sacco and Vanzetti case.

It is certainly possible that the Workers Party approached their contacts in the NAACP to inquire about involving them in the Sacco and Vanzetti campaign. However, if they did, there is no record of it in their public journals. If they had, for example, approached the NAACP about participating in one of the dozens of defense committees the communists helped establish and had been rebuffed, we can safely assume that the Daily Worker or the Labor Defender would have publicly noted this.

This only goes to show that solidarity across racial lines and between native-born and immigrant workers is rarely easy to achieve, and it was perhaps at its most difficult in the context of the Klan and Republican-dominated Roaring '20s.

DESPITE ITS shortcoming, the Workers Party in the 1920s broke new ground by developing a sustained and serious attitude toward fighting anti-Black racism and campaigning more openly against U.S. colonialism. Moreover, they explicitly linked both of these endeavors to their strategy for building unity within the American working class.

Lenin and the Bolshevik's great contribution to the American radical movement was to insist that exploitation and oppression had to be understood as a social totality that could not be overcome by downplaying one at the expense of the other. In order to do so, the party had to break with the radical wing of the labor movement's pre-war indifference to these questions. This was a tremendously important accomplishment, one which helped make possible the rise of larger and more successful working-class, anti-racist mobilizations in the 1930s.

Once they began this transformation, however, they were faced with the power of Jim Crow and the growing expansion of American imperialism. Segregation and racism had most often forced the workers' movement and the Black freedom struggle down separate tracks. Episodically they bent toward one another, but more often than not they were kept hostile and apart by the racism emanating from the exigencies of profit and saturating every level of society.

The American working-class movement was also compromised when it came to its record in opposing so-called Manifest Destiny, often seeing "free soil and free labor" as a panacea to the problems of capitalist exploitation, while remaining blind to the realities of genocide against indigenous peoples, colonial conquest such as the seizure of Mexican territory and the conquests of Guan, Puerto Rico, Cuba and the Philippines and the despicable history of exclusionary immigration laws targeting, especially, Asian workers. There were always exceptions to the rule, but they proved episodic and only partially developed.

None of this is to say that the Workers Party in the 1920s boasted a spotless record. Adding to their learning curve was the fact that the party was faction ridden and increasingly fell under the sway of the growing bureaucracy clawing its way to power in Russia. By the late 1920s, Stalin's henchmen had destroyed the revolution and imposed increasingly erratic and often downright bizarre policies on its Comintern affiliates. This is a well-known story and one that must be integrated into any history of the Workers Party in the 1920s.

But it would be wrong to read this outcome backward, as is too often done by friend and foe alike, treating the years of struggle by tens of thousands of communists as simply the prelude to a foregone conclusion. Even worse would be an attitude that refuses to learn the lessons those men and women gave so much of themselves to teach us. Hopefully this article has made a small contribution to recovering some of this legacy.

If the Workers Party can be faulted for their occasional scatter-shot methods, awkward initiatives and faulty expectations, its members must be appreciated for the contribution they made to a project which is as necessary today as it was then: the theoretical elaboration and practical merging of the politics of revolutionary socialism and liberation.