The first Bud Billiken

uncovers the forgotten story of a Chicago writer with a militant commitment to the fight for civil rights.

THE ANNUAL Bud Billiken parade on Chicago's predominantly African American South Side draws hundreds of thousands of people in early August each year (this year, on August 8), with a theme of encouraging Chicago kids to attend school.

The parade name is taken from a fictional character, "Bud Billiken," whose column "Bud says" appeared in the Chicago Defender newspaper, penned by several writers.

Over the last 20 years, the parade has become more of a citywide event, even though it's still staged on the South Side. Corporate sponsors and politicians dominate, many of them responsible themselves for the terrible state of public education in the city.

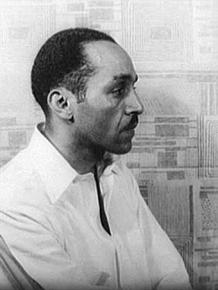

While this may be annoying, there is a hidden aspect of the parade that would surprise many--that the first Bud Billiken was African American novelist Willard Motley. Many parade participants and spectators would be even more surprised to learn that the Chicago-born and -raised Motley was a militant fighter for civil rights and active campaigner in one of the most controversial criminal defense cases in Chicago's history.

Most people walking Chicago's streets today wouldn't recognize Motley's name--even though, according to literary historian Alan Wald, he "was in all likelihood the most prolific novelist associated with the concluding years of the Black Chicago Renaissance."

BORN IN 1909 and raised in Englewood on the South Side of Chicago, Motley aspired from a young age to be a writer. As a teen, he wrote a children's column, using the pseudonym "Bud Billiken," in the Chicago Defender for a little over a year between December 1922 and January 1924.

Motley had an adventurous spirit, and soon after he graduated in 1929, he began a series of cross-country trips that netted him a small income as a travel writer. Many of the people he met on his travels provided raw material for his later novels. It's also important to recognize that Motley, according to friends and supporters, was gay--though not openly so, since this was a time when being Black and gay could have lethal consequences.

By the late 1930s, Motley was back in Chicago and lived in the Maxwell Street neighborhood around 14th and Union Streets, one the few multi-ethnic and multiracial neighborhoods in the city at the time. He helped launch Hull House Magazine in 1939, and the next year, he started working for the Federal Writers Project of the Works Project Administration, the New Deal era program that supported writers during the Great Depression.

With the approach of the Second World War, Motley began to take militant positions on political issues that would be characteristic for the rest of his life. "When the Selective Training and Service Act was passed in 1940, Motley declared that he would not serve in the segregated military," according to Wald. He filed for and received a conscientious objector status from the U.S. military.

While working as a lab technician, Motley spent the war years researching and writing what became his best-known novel Knock on Any Door. It quickly became a bestseller in 1947, selling over 47,000 copies in its first three weeks on the market and 350,000 over the next two years, and it was made into a popular 1949 film starring Humphrey Bogart.

The novel tells the story of Nick Romano, a street tough who kills a cop and is sentenced to death. Motley sees that Romano's tragic life is shaped by the poverty, bigotry and despair of his upbringing. He portrays Romano as a sympathetic character, and Motley's opposition to the death penalty is clear and eloquent at the climax of the story.

Motley, like the much better known Chicagoan Richard Wright, used his success to support causes for social justice. Soon after Knock on Any Door became a bestseller, he became an active member of the campaign to save James Hickman from the electric chair.

JAMES HICKMAN was an African American father of seven who shot and killed his landlord David Coleman in July 1947. Coleman, who was also African American, had made repeated threats to burn the tenants out of the building he leased at 1733 W. Washburne in Chicago. Coleman's tenants resisted his efforts to cut these tiny, shabby so-called "apartments" into even smaller ones.

Coleman apparently made good on his threats. Near midnight on January 16, 1947, A fire consumed the Hickmans' apartment, while James Hickman was working the night shift. Panic overwhelmed the family as they scrambled to escape the inferno. With only one stairwell, which was blocked by fire, and no fire escape, the only way out was through the one window in their apartment, and straight down three stories to the ground. Neighbors piled blankets on the ground below to break their fall.

James's wife Annie and his son Willis would survive the fire and the leap to the ground, but four of his children were found dead underneath the bed. The artist Ben Shahn would later immortalize this scene and the entire Hickman story in a series of illustrations in Harper's in 1948.

Hickman returned home the following morning to find his family gone. He later recounted to the respected Chicago journalist (and future U.S. Ambassador to the Dominican Republic) John Bartlow Martin that a neighbor approached him and broke the tragic news: "He said, 'Mr. Hickman, I hate to tell you this, four of your children is burnt to death.' And I weakened to the ground."

Hickman found his family, buried his children, moved into a new apartment and returned to work. The Chicago police didn't seriously investigate the case, despite testimony at the coroner's inquest of the deadly threats made by Coleman. Coleman would later be fined only a few hundred dollars for a housing code violation--small consolation for the Hickman family.

During the next six months, James's wife and surviving son became increasingly worried about his mental stability. James suffered terrible mood swings and near breakdowns.

On July 16, he picked up a gun and went to confront Coleman at his home on the South Side. He found Coleman sitting in a car outside his house and accused him of setting the fire. Hickman later claimed that Coleman admitted it. Hickman raised his pistol and shot him four times. Coleman was mortally wounded and died three days later.

Hickman went home, and was arrested without resistance and confessed to the shooting of David Coleman. The State's Attorney offices for Cook County (where Chicago is located) announced that they would charge Hickman with murder and seek the death penalty.

A defense campaign was organized to support Hickman by members of the Chicago branch of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party and leading labor activists in the city. They argued that the real cause of the death of David Coleman was the racist housing policies of the real estate companies and property owners that confined African Americans to housing in the South Side ghetto and tiny enclaves in the rest of city. If James Hickman and his family had been allowed to live wherever they chose, none of this would have happened.

Motley threw himself wholeheartedly into the Hickman defense campaign. His involvement opened many doors for supporters of Hickman. But one door that Motley couldn't open was to the daily Chicago Sun newspaper, one of the largest papers in the city.

Motley met Hickman in prison and wrote an eloquent appeal that the defense committee attempted to publish in the Sun. But Sun's owner, Marshall Field, heir to the Field family fortune and a well-known liberal, refused to print Motley's appeal, even though the defense committee was prepared to pay for the space. Motley publicly attacked Field for his hypocrisy, as one of those "rich liberals...who talk out of both sides of their mouths."

The defense committee had Motley's appeal circulated to many of the largest Black newspapers in the country, including the Chicago Daily Defender. Motley didn't hold back his feelings about the case when he wrote of visiting Hickman:

You have seen many pictures of men who have killed. You have seen the photographs of the returned soldier. Perhaps next door lives a boy who killed some other boy during the war. In the war, millions of men killed other millions of men because they believed they were a threat to their homes, their wives, their children. This threat was thousands of miles from home. These were strangers killed, with whom there had been no personal contact.

James Hickman killed the man who had threatened his wife and children with a death more horrible than the Nazi gas chambers. And carried it out. This is what I was thinking of as I sat talking to Hickman today. Hickman needs help. There are three children left who need him. A wife who needs him. Will you help us help him?

HICKMAN'S TRIAL lasted nine days in November 1947 and ended with a hung jury. The following January, the State's Attorney's office announced it wouldn't seek to retry Hickman because of the public outcry surrounding the case. Samuel Freedman, the assistant State's Attorney who prosecuted Hickman, belatedly concluded, "The state feels this man has paid enough with the loss of his children."

Soon after the victory in the Hickman case, Motley continued to take militant positions in an increasingly hostile political environment. He supported the 1948 Progressive Party campaign of Henry Wallace for president. Wallace had been Roosevelt's vice president during the Second World War, and he pledged, if elected, that he would continue the reforms of the New Deal, support civil rights, and pursue peace, not conflict, with Russia.

Wallace's presidential campaign was largely supported by the American Communist Party and was subjected to intense red-baiting through out the campaign. He would only garner 1 million votes in the election.

The following year, Motley became a public supporter of Jimmy Kutcher, a member of the Socialist Workers Party who was fired as a "subversive" from his job as a clerk in the Veterans Administration--though he didn't play the high-profile role in the Kutcher campaign that he did in the Hickman case.

Kutcher was a veteran who fought in some of the toughest battles in the early days of American involvement in the Second World War. His legs were irreparably mauled by artillery fire during the Italian campaign and were amputated later. He walked with prosthetics for the rest of life. It took a decade for Kutcher to win his job. Kutcher's story is recounted in his book The Case of the Legless Veteran.

In 1949, Motley also publicly supported the campaign to free 12 leaders of the Communist Party who were indicted under the repressive Smith Act. They were convicted and spent many years in prison. Henry Winston, the one Black defendant, went blind from lack of medical treatment in federal prison, and wasn't released until 1961.

Motley left the U.S. in the early 1950s to live in Mexico. He died there in 1965. Since his death, Motley has all but been forgotten, except by a handful of scholars. Chicago is a city that claims to be proud of its history--yet the story of Willard Motley/Bud Billiken is another one of the many examples of how people deemed "unacceptable" or "inconvenient" to the political establishment are thrown to the wayside. This is an unnecessary tragedy. Motley's papers, including hundreds of unpublished items, are archived at Northern Illinois University, just a short drive from Chicago.

The Bud Billiken parade organizers should put aside space and time to highlight the life and work of Willard Motley on parade day. Hopefully, when young people finish marching and get back to school this fall, they will have teachers who can tell them about the man who really was Bud Billiken.

Thanks to Alan Wald for his help in writing this article.