The making of the Russian Revolution

Russia was the first and only country to achieve a socialist revolution--that is, a society in which ordinary people had their hands on the levers of power. For that reason alone, the capitalist rulers of the world cannot allow that example to stand. Its history has been systematically distorted and buried, so it is up to Marxists today to cut through the myths and remember its lessons for today.

Russia 1917 will be the central theme of one-day conferences sponsored by SocialistWorker.org's publisher, the International Socialist Organization, taking place in cities around the country in November and December. Here, to provide an introduction to some of the questions and answers that will come up at the conferences, we are publishing excerpts from a special series on the Russian Revolution written a few years ago.

How the Stage Was Set for Revolution

Alan Maass | The Russian Revolution of 1917 is a reminder that the struggles which change the world often take place where they are not expected--where the possibilities of success seem least favorable.

The Russia of the Tsars was one of history's most terrible dictatorships. The vast majority of Russians lived in impoverished conditions that were little changed from centuries before. All were subject to the iron authority of the Tsarist regime and the Russian nobility. Various half-hearted attempts to reform the system from above--or, by contrast, to force change through failed assassination plots--had little if any effect on the lives of most Russians.

Yet this Russia was the setting for a revolution that gave us the only lasting glimpse so far of what a future socialist society--in which the mass of workers collectively and democratically control society--will look like.

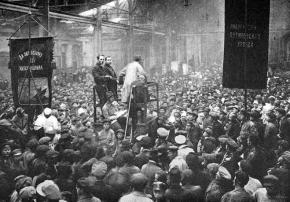

The Russian Revolution is the story of millions of people making history--"the forcible entrance of the masses into the realm of determining their own destiny," in the words of the Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky.

Russia's experiment in workers' power lasted only a few short years. The counterrevolutionary regime built on its ruins recreated all the oppressions of the old Tsarist system--and justified them with the rhetoric of socialism.

Nevertheless, the accomplishments of the revolution--in toppling one of the world's cruelest tyrants, in creating the first organs of mass workers' democracy, in bringing alive the talents and hopes of a whole society--remain a source of inspiration today.

The February Revolution

Kirstin Roberts | February 23 was International Women's Day, a socialist, working-class holiday in celebration of the struggles of working women to emancipate themselves and their class. As Leon Trotsky, one of the leaders of the Russian Revolution, later wrote: "The social-democratic circles had intended...meetings, speeches, leaflets. It had not occurred to anyone that it might become the first day of the revolution."

But the women textile workers of Petrograd came out on strike, and they dragged behind them the Bolshevik Party-led metal workers of the Vyborg district.

By the end of International Women's Day, 90,000 workers were on strike. The next day, the 24th, about half of Petrograd's workers were on strike, and large numbers were demonstrating in the streets. "The slogan "Bread!" wrote Trotsky, "is crowded out or obscured by louder slogans: 'Down with the autocracy,' 'Down with the war!'"

By the third day, large numbers of soldiers who had been mobilized to squash the demonstrations had instead joined the revolt, and could be seen using their weapons to shoot at police stations and liberate political prisoners.

One more day, and barracks of peasant soldiers in the cities--training to eventually take their turn in the trenches of the First World War, whose carnage fired the anger of the demonstrators--began to rebel openly and come over to the side of revolution.

Large numbers of these soldiers were mobilized by the most militant workers to seize the police stations, arrest government officials and army officers loyal to the Tsar, and drive troops loyal to the government out of the cities.

The Tsar's ministers fled or were arrested. Finally, on March 2, three centuries of Romanov rule came to an end, when the Tsar abdicated.

Lenin Prepares the Bolsheviks

Todd Chretien | The February Revolution in 1917 toppled the Romanov dynasty and replaced it with two competing governments.

The first, the Provisional Government, was an ad hoc formation peopled with large landowners and wealthy capitalists. Prince Lvov, a member of the aristocracy with a certain humanitarian reputation, assumed the title of president, while Alexander Kerensky, a radical lawyer and member of the Socialist Revolutionary party, became the Minister of Justice, lending an air of "radicalism" to the government.

On the other hand, the Soviet (which means "council" in Russian) of Workers, Soldiers and Peasants represented all categories of urban workers, the soldiers from the trenches and a wide swath of the peasantry.

Although this wasn't apparent to everyone involved, these two forms of government were inherently incompatible--because of the extreme contradictions between the needs of the ruling classes for profit and war, and the desires of the oppressed classes for land, bread and peace.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was largely fought out over the question of which half of this "dual power" would replace the other, and the attitudes of the various political parties towards this confrontation.

The Bolshevik leader Lenin returned to Russia from exile on April 3 and immediately presented a radical new policy to a divided Bolshevik Party, in what became known as the April Theses:

[T]he country is passing from the first stage of the revolution--which, owing to the insufficient class-consciousness and organization of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie --to its second stage, which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants...

No support for the Provisional Government; the utter falsity of all its promises should be made clear.

The hostility with which other socialist parties and even a number of Bolsheviks greeted the theses exposed the gulf between Lenin's view of a socialist revolution based on the self-emancipation of workers and poor peasants, and the other socialist parties' vision of a democratic capitalism based on shared power between the landlords and peasants, the officers and soldiers, and the bosses and workers.

How Workers' Power Was Organized

Amy Muldoon | Socialists embrace the Russian Revolution not just because a hated autocrat was deposed, but because the whole Tsarist system was overthrown by the most far-reaching, democratic movement of the oppressed that history has ever seen. The soviets (Russian for "councils") were the mechanism of the transformation and stand as a model of the creativity and efficiency of workers' self-rule.

The soviets first appeared in the 1905 Revolution in Russia, which was inspired by the fight for a shorter workday, but quickly led to a direct political assault on the despotism of the Tsar.

Initially created out of strike committees, the soviets rapidly evolved into organizing centers throughout Russia's major cities for the working class to debate and implement tactics in the struggle. The soviet was both a weapon of workers' power against the old system and the beginning of an accountable, democratic replacement.

Based on elected deputies, or delegates, from each workplace (in the case of peasants, by location, and in the case of soldiers, by units), the soviets were incredibly sensitive to the changing moods and demands of the population. With no perks or terms of office or bloated campaign funds, soviet representatives truly voiced the wishes of their constituents--or were soon replaced if they didn't.

The 1905 Revolution was defeated, but when the First World War drove Russian society to the brink of destruction, and sparked a revolutionary upheaval, the soviets re-emerged around the country to facilitate workers' struggle.

This time, however, the soviets were reproduced on a much wider scale--appearing among peasants, soldiers, even students and housewives--and were joined by other forms of workers' organizations.

The Revolt Against the Tsar's Empire

Sarah Knopp | When Russia's Tsar was toppled by the revolution of February 1917, his empire had a population that was 43 percent Russian and 57 percent non-Russian.

A majority of people--in Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, modern-day Belarus, the Ukraine, Georgia, Turkish Azerbaijan and Central Asia--lived under an occupation by a government whose language and laws were not their own.

In addition, Jews and other ethnic minorities spread throughout "Great Russia" suffered pogroms and persecution. There were hundreds of laws to restrict the rights of Jews and make them second-class citizens.

As Leon Trotsky later wrote in his History of the Russian Revolution, nationalism, tied up with the agrarian question, had been latent in areas like the Ukraine--and was released by the explosion of the February revolution.

In most of these places, peasants suffered under landlords drawn from the ruling classes of the stronger nations. In Volga, the Caucuses and Central Asia, for example, land was seized from tribes like the Bashkirs and Kirghiz, and given to wealthy Russians. Thus, the oppression of the peasantry went hand in hand with national oppression.

Among the lower classes in all the colonized areas, a fight for national independence was raised along with the general awakening of the human spirit brought about by the revolution. The poor peasants of these areas might fight under the banner of nationalism, but as Trotsky wrote, "their nationalism was only the outer shell of an immature Bolshevism."

All the different socialist tendencies in Russia, both those supporting and participating in the Provisional Government (chiefly, the Socialist Revolutionaries and Mensheviks), and those trying to overthrow it (the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin and Trotsky), claimed to support "self-determination." Programs are one thing, though, and content is another.

The Revolution Gains Strength

Paul D'Amato | Lenin's plan for the Bolsheviks seemed straightforward and simple: "Patiently explain" that all power must be taken by the soviets, and the experience of the working masses would itself move them leftward. This approach proved stunningly successful, winning the party thousands of new recruits.

But it also raised new and more difficult tactical questions related to the uneven character of the struggle--how to avoid the most advanced sections of the working class and soldiers in Petrograd moving faster than other parts of the country and creating a situation in which they would become isolated and crushed by the counterrevolution?

There were a number of factors creating this danger. One, the soldiers of the Petrograd garrison, numbering about 300,000, were quickly radicalized by their opposition to the military offensive and the impending possibility of transfer to the front, so they felt they had to act.

Second, the Petrograd workers, particularly in the Vyborg district, where the city's major factories were concentrated, had already by June, if not earlier, gone over to support Bolshevik demands. The same was true for the sailors of Kronstadt and the Baltic fleet. Third, anarchists were conducting a high-pitched agitation in favor of immediate overthrow of the provisional government, and were gaining a growing hearing.

All these factors were pulling the Petrograd Bolsheviks to the left and compelling them to act.

The result was a series of demonstrations; one in April, one in June, and one in July--each time larger, better armed and more militant--which threatened to spill over into street fighting and a premature bid for power in Petrograd.

Demonstrations were necessary as a method of probing the enemy and counting forces. But there was the constant danger of premature confrontations. Several times, Lenin and the Bolshevik Central Committee had to pour cold water on the party's hotter heads.

Repression and Resurgence

Paul D'Amato | For the first few weeks after the July Days demonstrations--a premature armed uprising that wasn't supported by the mass of Russian workers--it seemed that the reaction might be victorious. The aftermath produced a wave of demoralization among workers and soldiers.

There was a brief orgy of attacks, both physical and political, against the Bolshevik Party, but clearly intended as part of a more general reaction against the entire left. Hundreds were arrested, including Kamenev, the Kronstadt Bolshevik leader Raskolnikov and other leading Bolsheviks. Fearing for his life, Lenin went into hiding, along with Zinoviev. Trotsky was also arrested.

But in the end, the reaction was relatively short-lived, and the movement bounced back in a matter of a month--stronger, deeper and broader. Suspicious of the government still and alarmed by the specter of counterrevolution, Russian workers refused to give up their arms.

The greater the threat of reaction, the more the Bolsheviks were welcomed as the guardian of the revolution's left flank. While the party's recruitment briefly stopped, it lost very few members, and its organization survived the period intact.

The local district soviets--which were more in touch with the rank-and-file mood--showed little interest in attacking Bolsheviks. What most interested them was preventing the government from disarming the workers, stopping left-wing soldiers from being sent to the front, resisting the reinstitution of the death penalty at the front, and challenging the growth of the extreme right.

All these concerns led straight back to the revival of the Bolsheviks' standing and the lowering of the standing of the moderate soviet leaders, who were even more strongly allied with the Provisional Government now than before the July Days.

How Kornilov Was Defeated

Jen Roesch | By August, Gen. Kornilov emerged as the leading figure around which the right-wing forces were gathering. The head of the Provisional Government, Kerensky, had appointed Kornilov commander of the armed forces in early July, but he was rightly seen by the masses as the face of counter-revolution.

When he organized a military assault on Petrograd, workers moved into action with a practical defense of the capital through a popular mobilization.

With the official government paralyzed, the Committee for Struggle formed by the Petrograd soviet became the command center for the defense. To this was joined an extraordinary mobilization of the masses from below. Ad-hoc revolutionary committees sprang up everywhere. Between August 27 and 30, more than 240 were created across Russia. Local organizations led the fight in every arena.

The Bolsheviks demanded the arming of the workers and formed workers' militias. Lines of workers signed up to become "Red Guards," and the Bolshevik Military Organization took the lead in their training and deployment. Unarmed workers dug trenches, erected barbed wire fencing around the approaches to the city and built barricades.

At the Putilov works, workers labored through the night to finish construction of weapons that were then sent to the field without testing. Metal workers accompanied the weapons to the field and adjusted them on the spot.

The railway and telegraph workers played a particularly decisive role. "In a mysterious way, echelons would find themselves moving on the wrong roads," Trotsky wrote. "Regiments would arrive in the wrong division, artillery would be sent up a blind alley, staffs would get out of communication with their units."

Meanwhile, teams of agitators were sent out to argue with Kornilov's troops. Many of the soldiers had not been told why they were being sent towards Petrograd, and they turned on their officers. In one division, the troops raised a red flag inscribed "Land and Freedom" and arrested their officer.

Within four days, the Kornilov plot had collapsed. His forces disintegrated as the workers and soldiers again took the center stage of revolution.

The Party and the Revolution

Paul D'Amato | The argument that the Bolsheviks "hijacked" the revolution fails to take into account that the Bolsheviks were only one political party among many competing for the support of the Russian people.

The fact that the Bolsheviks were able to win mass support away from the Social Revolutionaries and Mensheviks flowed not from their superior persuasive powers or ability to command blind obedience, but because of their program.

They were the only party that demanded land to the peasants, factories to the workers, all power to the soviets and an end to the war. "All other major political groups," writes historian Alexander Rabinowitch, "lost credibility because of their association with the government and their insistence on patient sacrifice in the interests of the war effort."

In short, whereas the other parties acted as a brake on the revolution, the Bolsheviks wanted to see it through to the end.

At the same time, the party was not for some kind of minority putsch against the Provisional Government led by Kerensky. Lenin and other party leaders worked to restrain the movement when they felt that a premature revolt threatened the movement as a whole with defeat.

Lenin's bold and determined leadership, as well as the Bolsheviks' relative unity and discipline compared to other political parties, were key factors in the revolution's success.

But this unity and discipline was not bureaucratic--it was organic and political. The party debated and voted on all key questions, and local organizations of the party possessed a great deal of leeway to carry on their own independent initiatives.

Rabinowitch attributes much of the Bolsheviks' success in transforming themselves from a party of 25,000 on the eve of the February Revolution into a mass party capable of leading a successful struggle for power with a membership of a quarter million to "the party's internally relatively democratic, tolerant and decentralized structure and method of operation, as well as its essentially open and mass character."

The Final Act of the Revolution

Michele Bollinger | The defeat of the coup attempt led by Kornilov at the end of August set the stage for the final act of the Russian Revolution.

The crucial moment arrived in October when the Kerensky government suddenly announced plans to move the bulk of the Petrograd garrison--now as much a center of the revolution as the city's factories--to the front. "In unison," Rabinowitch wrote, "garrison troops proclaimed their lack of confidence in the Provisional Government and demanded the transfer of power to the soviets."

The Military Revolutionary Committee sent its own commissars to replace the government's representatives in all garrison units. The committee issued an order that "no directives to the garrison not signed by the Military Revolutionary Committee should be considered valid."

Effectively, the soviet had taken control of the armed forces in Petrograd away from Kerensky--"disarming the Provisional Government without firing a shot," Rabinowitch writes.

Meanwhile, preparations were taking place for the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets from throughout the country--where the Bolsheviks were certain to have the majority of delegates.

On the eve of the congress, the Provisional Government made a last attempt at a crackdown. For example, Kerensky ordered the bridges raised in the center of the capital to disrupt movement--as the Tsar had done during the February Revolution.

The Military Revolutionary Committee's countermoves were coordinated out of the Smolny Institute--formerly a woman's boarding school, which had been taken over as the central headquarters of the Petrograd soviet, and where the leaders of the Bolsheviks and other revolutionary groups gathered.

Late on October 25, detachments of armed workers seized the Winter Palace, where Kerensky had holed up with other top officials of the Provisional Government. Kerensky himself had fled hours earlier. The remaining ministers were arrested without a fight.

The next morning, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets convened and adopted a decree transferring power to the soviets. The Provisional Government had been toppled, and the demand for "All Power to the Soviets"--the embodiment of workers' democratic self-rule--was made a reality.

The Legacy of 1917

Alan Maass | The tragedy of the Russian Revolution is that it only survived for only a brief period of time, besieged by civil war, imperialist intervention and economic crisis. Ultimately, the revolution was overthrown, but in a form no one expected--a new ruling class came to power on the ruins of the workers' state, but it ruled in the name of "socialism."

Nevertheless, in spite of everything Stalinism did to discredit socialism, the defenders of the status quo today haven't stopped slandering the Russian Revolution of 1917. Even as a memory of a struggle from a distant time under very different conditions, it remains a threat.

Near the end of his brilliant History of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky quotes a former Tsarist general, whose word sums up the ruling class' enduring hatred of the Russian Revolution.

"Who would believe that the janitor or watchman of the court building would suddenly become Chief Justice of the Court of Appeals?" the general said. "Or the hospital orderly manager of the hospital; the barber a big functionary; yesterday's ensign the commander-in-chief...yesterday's locksmith head of the factory?"

Who indeed? This was the promise of the Russian Revolution and the tragedy of its defeat after only a few short years--that society could be remade without privileges and power for the few; remade without a small minority born to rule and the rest ruled; remade without the stultifying oppression, exploitation and alienation that afflicts almost everyone under capitalism.

That promise remains to be realized--and to do it, the history of the Russian Revolution needs to be uncovered and understood by a new generation of revolutionaries so its lessons can be put to use in the ongoing struggle for a socialist society.