Intro to Chomsky

Noam Chomsky has been a dedicated opponent of war and injustice for more than half a century. His dozens of books and writings for innumerable journals have made him one of the best-known radical voices in the U.S. and around the world, responsible for contributing to the commitment and shaping the thinking of countless people.

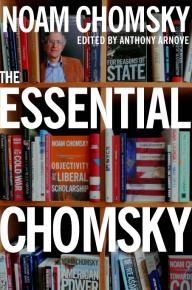

This year, the New Press published The Essential Chomsky, a collection of Chomsky's writing on not only politics, but linguistics and more. The book was edited by SocialistWorker.org columnist , author of Iraq: The Logic of Withdrawal. Here, we republish Anthony's introduction from the book, with permission from him and New Press.

FROM HIS early essays in the liberal intellectual journal The New York Review of Books, to his most recent books Hegemony or Survival, Failed States and Interventions, Noam Chomsky has produced a singular body of political criticism.

American Power and the New Mandarins (1969), his first published collection of political writing (dedicated "To the brave young men who refuse to serve in a criminal war"), contains essays that still stand out for their insight and biting sarcasm nearly four decades later. "It is easy to be carried away by the sheer horror of what the daily press reveals and to lose sight of the fact that this is merely the brutal exterior of a deeper crime, of commitment to a social order that guarantees endless suffering and humiliation and denial of elementary human rights," Chomsky wrote in that book, setting himself apart from the vast majority of the war's critics who saw it as a "tragic mistake," rather than as a part of a long history of U.S. imperialism.

Since 1969, Chomsky has produced a series of books on U.S. foreign policy in Asia, Latin America and the Middle East, all the while maintaining his commitments to linguistics research, philosophy and to teaching. And throughout, he has consistently lent his support to movements and organizations involved in efforts for social change, continuing a tradition of intellectual and active social engagement he developed early in his youth.

Avram Noam Chomsky was born in Philadelphia on December 7, 1928, and raised among Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father, William Chomsky, fled from Russia in 1913 to escape conscription into the Tsarist army. His mother, Elsie Simonofsky, left Lithuania when she was one year old. Chomsky grew up during the Depression and the rise of the fascist threat internationally. As he later recalled, "Some of my earliest memories, which are very vivid, are of people selling rags at our door, of violent police strikebreaking and other Depression scenes."

Chomsky grew up around working-class people, ideas and organization, and was imbued at an early age with a sense of class solidarity and struggle. While his parents were, as he puts it, "normal Roosevelt Democrats," he had aunts and uncles who were garment workers in the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union, Communists, Trotskyists and anarchists.

As a child, Chomsky was influenced by the radical Jewish intellectual culture in New York City. He regularly visited the Jewish anarchist newspapers and bookstores on Fourth Avenue. According to Chomsky, this was a "working class culture with working class values, solidarity, socialist values...Within that it varied from Communist Party to radical semi-anarchist critique of Bolshevism. That whole range was there."

After having almost dropped out of the University of Pennsylvania, where he had enrolled as an undergraduate when he was 16, Chomsky found intellectual and political stimulation from the Russian linguist, Professor Zelig Harris. Influenced by his parents, both of whom taught Hebrew, Chomsky gravitated toward the unusual intellectual milieu around Harris.

Harris taught seminars on linguistics that involved philosophical debates, reading and independent research outside the standard constraints of the university structure. Chomsky began graduate work with Harris, and in 1951 joined Harvard's Society of Fellows, where he continued his research into linguistics.

By 1953, Chomsky had broken "almost entirely from the field as it existed," and was soon publishing path-breaking work, drawing on the 17th century linguistics of the Port-Royal school and the French philosopher René Descartes, and the later work of the Prussian philosopher William von Humboldt, on the "creative aspect of language use." Though Chomsky would at times downplay or deny the connection, his political and linguistic work have both built on the idealist philosophical tradition that he has traced back from anarchism through "classical liberalism" to the Enlightenment and the early rationalists of the 17th century.

WHILE CHOMSKY, who joined the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1955 at the age of 26, received tremendous early recognition for his linguistic work, he began to make a wider political mark when he started writing long, detailed essays denouncing the war and the role of mainstream intellectuals who supported it for the New York Review of Books and then for left journals such as Liberation, Ramparts, New Politics and Socialist Revolution (later Socialist Review).

These essays brilliantly documented and condemned the actions of the U.S. government in Indochina and connected the war effort to the history of U.S. imperialism more generally. Chomsky became one of the most important and respected critics of the U.S. war effort, earning a place on President Nixon's infamous "enemies list." From this point on, he was the subject of intense vilification by various apologists of the system, much as he would later be subjected to repeated attacks for his critical writings on Israel.

In these early essays, we see Chomsky developing the basic themes of his best work: rigorously detailed analyses of U.S. planning documents, declassified records, official statements and hard-to-find sources; merciless critiques of liberals, establishment intellectuals and media commentators who provided a cover for U.S. imperialism; and an analysis that showed that the war in Vietnam was not the result of "mistakes," "honest misunderstanding," "attempts to do good gone awry"--or of bad or incompetent officials who could just be replaced by better ones. Rather, the war against Indochina was a product of systematic, deeply rooted features of the capitalist state.

Not just an intellectual critic of the war against the people of Indochina, he participated in direct action to back up his beliefs. Chomsky took part in one of the first public protests against the war in Boston in October 1965, at which protesters were outnumbered by counter-demonstrators and police, and became an important day-to-day organizer in the movement. These commitments extended well beyond Vietnam to involvements in the Central American solidarity movement, protest against the 1991 and 2003 U.S. interventions in Iraq and much more.

Chomsky has continued to speak out, write, give interviews, sign petitions and reach out individually wherever he feels he might be able to make a difference. And yet, he has also maintained his passionate engagement with his students and others in the field of linguistics, an area where he has continued to develop his theories and work.

People around the world take inspiration from Chomsky's example, and rightly so. He reminds a world that sees the United States through the lens of Fox News, or that experiences the United States through its blunt instruments of foreign control, that the people of the country have far different values and ideals. He speaks within a vital but often neglected tradition of dissent and from a standpoint of solidarity with literally all of those around the world who are engaged in a struggle for justice and social change.

On his trips to countries such as Colombia and Bolivia, usually with Carol Chomsky, he travels more to learn from the struggles of others than to teach or instruct, but his words still carry the immense power that criticism and analysis at its best can exemplify: the power of people to understand the world in order to better understand how to change it.