No profit in housing the homeless

The mortgage crisis has caused a "glut" of vacant homes in the U.S. But as explains, under the free-market system, those homes are more likely to be destroyed than provided to the homeless.

IT'S NO secret that one of the key problems in the U.S. housing market is that there are more houses for sale than buyers for them. Because of the mortgage crisis that caused home values to plummet and banks to tighten up their requirements for making new mortgage loans, the pace of sales has slowed way down.

Currently, there are 4.5 million existing homes for sale, or a nearly 11-month supply at the current pace of sales. There are also 453,000 new homes on the market, also an 11-month supply.

In short, there are way too many homes than can be sold for a profit (not to mention growing supplies of vacant condominiums and apartments). Until a real dent is made in this supply of vacant housing, prices will continue to fall.

As it stands, even though construction of new homes has dropped precipitously, the vacant supply is rising, not falling, as homeowners who can't afford mortgages put their homes up for sale--plus houses that were foreclosed upon also go on the market.

What's the extent of the problem? New data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that the combination of people losing their homes and continued construction of unaffordable new homes means that 18.5 million out of the estimated 129 million housing units in the U.S. now sit vacant--a whopping 14.3 percent.

According to the Census Bureau, U.S. households on average have 2.57 people. So the vacant housing stock could provide homes to at least 47.5 million people--or about 15 percent of the U.S. population. And that's a conservative estimate when you consider that many vacant houses could comfortably house many more people than the household average.

To put this number in perspective, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration estimates that 3.5 million people in the U.S. experience homelessness in a given year, and about 842,000 people are homeless in any given week. So there are enough vacant homes to house the homeless in any given week 56 times over.

Further, in 2005, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights estimated the global homeless population at 100 million. So, roughly speaking, there is enough vacant housing to provide shelter for nearly half the world's homeless population in the U.S. And when you factor in the growing amount of vacant commercial real estate, such as office buildings and shopping centers, an even further dent could be made.

UNDER A sane system, this would be fantastic news--homelessness could be wiped out entirely in the United States, and large parts of the globe. But under capitalism, it's bad news.

Consider the situation in New Orleans. Nearly three years after Hurricane Katrina, up to 200 of the 1,000 "chronically homeless" in the city camp out nightly underneath a filthy highway underpass. The camp sits literally a few hundreds yards away from a massive public housing project that the city emptied, surrounded with razor wire and has been trying to demolish ever since the storm.

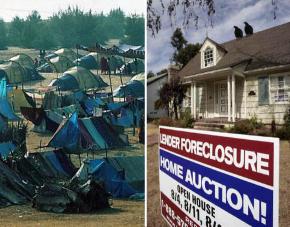

Meanwhile, in the Southwest, tent cities are arising, occupied by people who lost their homes to foreclosure. The city of Santa Barbara, Calif., for example, has set aside 12 parking lots to allow people who lost their homes to live out of their cars. In many cases, the people living in the lots still have jobs, but simply can't find affordable housing.

CNN interviewed Barbara Harvey, a 67-year-old mother of three children currently living out of her SUV with two golden retrievers. Harvey was laid off a year ago from a job that nevertheless paid so little she was still paying three-quarters of her income toward housing. Two months ago, she was forced out of her condo. "It went to hell in a hand basket," she told CNN. "I didn't think this would happen to me. It's just something that I don't think people think is going to happen to them, is what it amounts to. It happens very quickly, too."

Harvey now works part time for $8 an hour, and she draws Social Security to help make ends meet, but that's not enough to afford apartments in a community where the median house price is more than $1 million.

What other solutions are being offered? Rather than trying to occupy vacant houses, Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke suggested that cities and states should destroy vacant homes to help bring supply and demand back into balance.

In a speech in March, Bernanke praised the Genesee County Land Bank in Flint, Mich.--a "highly depressed" market, in his words--for acquiring vacant units through tax liens and demolishing them. Bernanke sniffed that such programs could "mitigate safety hazards and reduce supply."

Meanwhile, Lawrence Lindsey, a former assistant to the president on economic policy in the Bush administration and a leading proponent of Bush's $1.35 trillion tax cut for the rich, wants to tap immigrants to buy the houses.

Sounds great, right? Only it turns out that Lindsey isn't thinking of undocumented workers. Instead, he has proposed a plan to grant "provisional green cards" to any foreign investors willing to spend at least $10 million to buy groups of residential properties and hold them for five years. His logic? By luring up to 100,000 investors to buy properties, $1 trillion would be pumped into the housing industry.

How does that makes it any easier for people to actually live in these houses? That's not something Lindsey has an answer for.

All these examples illustrate in stark terms that the interests of capitalism lie only in making a profit and not meeting human need. Another kind of society is not only desirable, but necessary.