Life under the occupiers

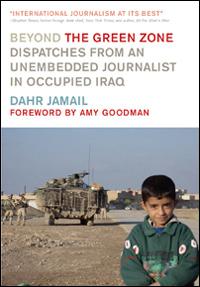

Beyond the Green Zone: Dispatches from an Unembedded Journalist in Occupied Iraq is Dahr Jamail's critically acclaimed, indispensable account of life in Iraq under the U.S. occupation.

The book goes past the polished desks of the corporate media and Washington politicians to tell firsthand the reality of life in Iraq. This lively book offers lyrical journalism, personal reflection, incisive analysis and groundbreaking reportage, including previously unpublished details of the first years of the U.S. occupation.

Dahr's writings on the Middle East can also be found at Dahr Jamail's MidEast Dispatches Web site. Beyond the Green Zone has been reissued in paperback with an updated afterword. Here, with permission, we reprint Dahr's afterword.

This fall, Dahr will join other authors on the Resisting Empire speaking tour, organized by Haymarket Books.

ON FEBRUARY 10, 2005, I traveled to Rome to provide testimony at a tribunal regarding Western media complicity in the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. The World Tribunal on Iraq (WTI) was an international peoples' initiative seeking the truth about the war and occupation in Iraq. The tribunal had already held meetings focusing on different aspects of the invasion and occupation, in cities such as Brussels, London, Mumbai, New York, Hiroshima, Copenhagen, Stockholm and Lisbon. The WTI found much of the Western media guilty of deceiving the international community and inciting violence with its reporting of Iraq.

The informal panel of WTI judges at the tribunal accused the governments of the United States and Britain of impeding journalists in performing their task, as well as producing lies and misinformation. The judges found that the corporate media reportage on Iraq was guilty under article six of the Nuremberg Tribunal, set up to try Nazi crimes, which states: "Leaders, organizers, instigators and accomplices participating in the formulation or execution of a common plan or conspiracy to commit any of the foregoing crimes (crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity) are responsible for all acts performed by any persons in execution of such a plan." For example, the tribunal found that Judith Miller of the New York Times was a part of this problem, having written numerous uncritical stories about alleged weapons of mass destruction in Iraq prior to the U.S.-led invasion.

Though I was exhausted and suffering symptoms of PTSD, providing testimony in front of the WTI panel that could help highlight the guilt of the mainstream media was an important moment for me. It was, after all, the complicity of the media that had initially led me to Iraq. While the majority of people in the United States remained largely ignorant of how complicit the corporate media truly was, the majority of the rest of the world appeared to understand this. This fact was underscored when later that summer I provided testimony at the culminating session of the WTI, in Istanbul, Turkey. The huge meetings were attended by more than 300 journalists from around the globe, but not a single representative from the U.S. mainstream media.

Meanwhile, the situation in Iraq continued to decline. The results of a survey taken by the respected group World Public Opinion, released on September 27, 2006, found that more than 70 percent of Iraqis wanted the U.S. military to leave within a year, and by a wide margin Iraqis believed U.S. forces provoked more violence than they prevented. Iraqis who supported attacks on U.S. forces had jumped to 61 percent, up from 47 percent less than a year earlier. By October 2006 the number of attacks against American troops had reached "unprecedented levels," according to the U.S. military. The Pentagon's quarterly report, released on November 30, 2006, stated that U.S. military and Iraqi security forces were being attacked more than eight hundred times every week, an average that had risen over 100 percent since the summer of 2005, and since January 2006, sectarian executions had increased more than fivefold.

By late 2007, about 70 percent of Iraqis believed security had deteriorated in the area covered by the U.S. military "surge" according to a BBC/ABC News/NHK opinion poll. Like earlier surveys, this poll found 60 percent of Iraqis considering attacks against U.S.-led forces as justified. By March 2008, 70 percent of Iraqis still wanted occupation forces to leave, according to an ORB/Channel 4 News survey.

Yet, as from the very first day of the invasion, it was the Iraqi people who continued to pay the highest price.

On October 11, 2006, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Medicine, in coordination with Iraqi doctors from al-Mustansiriya University in Baghdad, published the horrifying results of their scientific study of "excess deaths" in Iraq. Published in the peer-reviewed, prestigious Lancet medical journal in the United Kingdom, the study found that 655,000 excess deaths (2.5 percent of the entire population of Iraq) had occurred since the invasion and occupation in March 2003.

Eight days after the study was published, in another blatant example of censorship, the office of U.S.-backed Iraqi prime minister Nuri al-Maliki instructed the Iraq Health Ministry to stop providing mortality figures to the UN. According to the prime minister's directive, the prime minister's communications director would be responsible for "centralizing and disseminating such information in the future."

Meanwhile, Iraqi medics announced that as many as half of the 655,000 deaths in Iraq would have been preventable had it not been for the fact that even the most basic treatments were lacking. More than 200 doctors, nurses and pharmacists had been killed and more than 18,000 others--more than half of all Iraqi doctors--had fled the war-torn country. Iraqi doctors had been begging the international community to help stem the soaring death rate and assist in easing the suffering of their people but found that governments, along with the international medical community, ignored their plight. An International Committee for the Red Cross report in early 2008 stated, "It is shocking to see how Iraqis today lack the most essential needs in terms of health services."

The death toll in Iraq continues to mount daily, and two staggering results, by different groups, confirm this. The U.S.-based group Just Foreign Policy put the figure at just over 1.2 million dead in July 2008. In September 2007, a British Opinion Research Business survey estimated 1,220,580 Iraqis had been killed.

WITH BILLIONS of dollars allocated for reconstruction missing, due to a combination of criminal activity, corruption, and incompetence, it was not surprising that Iraqis were without the essentials of basic medical treatment. The country had never recovered from the genocidal sanctions that ran from 1990 to 2003. Even common aids like gauze, aspirin and medical tape continued to be scarce. The group Medact reported, "Easily treatable conditions such as diarrhea and respiratory illness caused 70 percent of all pediatric deaths," and said that "of the 180 health clinics the U.S. hoped to build by the end of 2005, only four have been completed and none opened."

Dr. Bassim al-Sheibani and his colleagues at the Diwaniyah College of Medicine told reporters, "Emergency departments are staffed by doctors who do not have the proper experience or skills to manage emergency cases. Medical staff...admit that more than half of those killed could have been saved if trained and experienced staff were available. Many emergency departments are no more than halls with beds, fluid suckers and oxygen bottles." As if that were not bad enough, hospitals had been a place of refuge for those hoping to escape the rampant violence. Now Iraqis were going out of their way to avoid them.

Public hospitals in Baghdad were controlled by the Shia, who had given death squads free access to enter and kill Sunni patients. Abu Nasr, whose cousin was injured in a car bomb and then dragged from his hospital bed and riddled with bullets, told the Washington Post: "We would prefer now to die instead of going to the hospitals. I will never go back to one, never. The hospitals have become killing fields." An Oxfam International and NCCI (a network of aid organizations working in Iraq) report in July 2007 stated that nearly one in three Iraqis (8 million) were in need of emergency aid. In addition, 4 million Iraqis regularly could not buy enough to eat, more than one in four Iraqi children were malnourished (compared to less than one in five under the genocidal sanctions), nearly half of all Iraqis lived in abject poverty (on less than one dollar per day), and 70 percent of Iraqis lacked adequate water.

In December 2006, Iraq's minister of labor and social affairs, Mohammed Radhi, said that unemployment remained at approximately 50 percent. This number remains the same, as of the time of this writing. In January 2007 it was announced that Iraq's inflation rate averaged 70 percent throughout 2006. Electricity production remains far below prewar levels, and has never exceeded them. By every account, Iraq's infrastructure is in shambles. According to the Iraqi government, an estimated $100 billion was required over four to five years to rebuild its shattered infrastructure. Not surprisingly, on October 31, 2006, at a news conference in Kuwait, Iraqi government spokesperson Ali al-Dabbagh announced, "The situation in Iraq surpasses Iraq's ability to finance development projects."

But it has become commonplace for Western companies--who often receive no-bid contracts, operate without any accountability, and refuse to make their profit margins transparent--to abandon, or even fail to begin contracted projects. For instance, San Francisco–based Bechtel Corporation completed only $2.3 billion of a $3 billion contract before leaving Iraq entirely in November 2006.

On February 26, 2007, Iraq's cabinet approved a draft of an oil law that would set guidelines for nationwide distribution of oil revenues and foreign investment in Iraq's giant oil industry. The law would grant regional oil companies the power to sign contracts with foreign companies for exploration and development of oil fields, and open the door for investment by foreign oil companies. If passed by the Iraqi Parliament, this law will open Iraq's currently nationalized oil industry to private foreign oil companies with terms never seen before in the Middle East. It is worth noting that the consulting company Bearing- Point, which is based near CIA headquarters in MacLean, Virginia, was commissioned by USAID to advise the Iraqi Ministry of Oil on drawing up a new hydrocarbon law. The U.S.-designed Iraqi law sets up an oil and gas council that could theoretically be populated by employees of multinational oil corporations and other U.S. corporate advocates, and could allow PSAs (whose wording was changed to "Exploration and Risk Contracts" in the latest draft of the law) in which American firms would enjoy an initial 70 percent profit from Iraqi oil extraction. After Bearing Point had prepared the early draft of the oil law, it was sent to the White House, several Western petroleum corporations, the British government, and then to the International Monetary Fund.

DURING THIS time, most Iraqi legislators and the general public knew little to nothing about it. The law, as well as the drafting process, was immediately criticized by analysts and labor groups, who warned that the bill is skewed in favor of foreign companies. The law specified that up to two-thirds of Iraq's known oil reserves could be developed by multinational corporations under contracts lasting up to 35 years. At the time of this writing, the law was fully expected to be ratified by the Iraqi parliament because powerful faction leaders in the government had already cleared it. Iraq's vice president, Abdel Mahdi, when he was the minister of finance, had already said that this law would be "very promising to the American investors and to American enterprise, certainly to oil companies." The law mirrors proposals that were originally written by the Bush administration before the invasion even began. Over the course of several meetings between December 2002 and April 2003, members of the U.S. State Department's Oil and Energy Working Group agreed that Iraq "should be opened to international oil companies as quickly as possible after the war" and that the "best way to facilitate this would be via production-sharing agreements."

The guidelines that form the basis of the current proposed oil law, which could give foreign companies control of two-thirds of Iraq's oil, are based on proposals submitted by Iraq's U.S.-appointed prime minister Iyad Allawi. He recommended that the "Iraqi government disengage from running the oil sector" and that all undeveloped oil fields in Iraq be turned over to private international oil companies using PSAs. In October 2006, Petroleum Economist magazine reported that U.S. oil companies had put the passage of this oil law before their security concerns as the deciding factor over their entry into Iraq. By June 2008, four Western oil companies were in the final stages of negotiations on contracts that will return them to Iraq, 36 years after losing their oil concession to nationalization. ExxonMobil, Shell, Total, and BP--the original partners in the Iraq Petroleum Company--along with Chevron and a number of smaller oil companies, were poised for no-bid contracts to service and exploit Iraq's largest fields. As far as the other reason for the occupation, the geostrategic positioning of the U.S. military, we need only look at the Quadrennial Defense Review released in February 2006. That report tells us that the U.S. military must be prepared to fight "multiple overlapping wars" and to "ensure that all major and emerging powers are integrated as constructive actors and stakeholders into the international system."

Adding insult to injury, during the autumn of 2006, Iraq, in a state of nearly complete and total political and economic collapse, was forced to pay more than $21.4 billion in "war reparations" to some of the richest countries and corporations in the world, on top of $41.3 billion previously paid in recompense for the 1991 Iraq War, in which Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

On June 6, 2008, it was revealed the U.S. government was holding hostage $50 billion of Iraq's money in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in order to pressure the Iraqi government into signing an agreement that would prolong the occupation indefinitely. The pact would also provide U.S. soldiers in Iraq with legal immunity. The vast majority of Iraqis, at least 70 percent, oppose a continuance of the occupation, thus the puppet government was in a precarious situation.

Yielding to U.S. pressure, 20 days later, Iraqi president Jalal Talabani spoke of progress toward the deal to secure the U.S. presence. Speaking after talks with George W. Bush, Talabani said both sides had made "very good, important steps towards reaching...this agreement." The Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) has led to widespread protest in Iraq when media reports stated the United States was demanding immunity for mercenaries and that the deal allowed the presence of more than fifty permanent military bases in the country. Also in late June, Sunni legislator Khalaf al-Alyan told a reporter, "The Iraqi-U.S. agreement contains several items that impinge upon the sovereignty of Iraq, including the right of the U.S. forces in Iraq to attack any nation and raid any Iraqi house and arrest people without prior permission from the Iraqi government."

MOST OF the Iraqis I met in Iraq have either fled or been killed. Salam had long since fled after receiving a death threat. His brother, whom I'd met during my last trip in Iraq, was later gunned down in broad daylight. I had been pleading with Harb to leave for months. His reply was always, "Habibi, my heart is in Baghdad. I can never leave." But by fall 2006, the situation had become so intolerable that he had taken his wife and young sons to Damascus. Ghreeb, who had assisted us in entering Falluja during the April assault, had been killed by unknown gunmen. Dr. Aisha from Yarmouk Hospital, whose brother was killed, his body dropped off at her hospital after she had returned from a speaking tour in the United States, fled the country and applied for political asylum. Suthir, who had taken me to al-Dora to chronicle the collective punishment being meted out there during my last trip, also fled with her family. Hamoudi took his family and fled to the Kurdish-controlled north of Iraq, after receiving a death threat. On June 12, 2007, Sheikh Adnan was kidnapped from his car, and is now presumed dead. The few others I met during my time in Iraq who remain do so under conditions that resemble something akin to prison or house arrest under the direst of conditions.

By February 2007, Iraq was experiencing the largest exodus in the Middle East since Palestinians were forced to flee their homes in 1948 amid the creation of the state of Israel. The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) announced that 50,000 Iraqis every month were abandoning their homes. UNHCR regional representative Stephanie Jaquemet announced that 2 million Iraqis had fled abroad and another 1.5 to 2 million were displaced within Iraq.34

By spring 2007 at least one out of every six Iraqis had fled their homes since the invasion of March 2003. Ken Bacon, the president of Refugees International, told a U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in January 2007, "This is the fastest growing refugee crisis in the world. The U.S. has a special obligation to help, since the violence in Iraq and the growing displacement comes in the aftermath of our invasion and occupation." At the same hearing, the Bush administration's senior refugee official, Assistant Secretary of State Ellen Sauerbrey, said that the Bush administration, which was spending roughly $30 million per day on military operations in Iraq, had only earmarked $20 million for Iraqi humanitarian needs in bilateral aid for all of 2007. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated there were at least 4.7 million Iraqi refugees, inside and outside of the country, in June 2008. "Many refugees are finding it difficult to survive," Philip Luther, Deputy Director of Amnesty International's Middle East and North Africa Program stated in a report in June 2008, "They are banned from working and unable to pay rents, buy adequate food for themselves and their families, or obtain medical treatment. Those lucky enough to escape Iraq rely on savings which, for many, are rapidly running out."

By January 2007 the Bush administration had only granted refugee status to 466 Iraqis since 2003. In February of that year, the Bush administration announced it would take in 7,000 Iraqi refugees, roughly the number flooding out of Iraqi borders every four days, but did not say who would be chosen and how. By late June 2008 the Bush administration had admitted a meager 4,742 Iraqis into the United States since the invasion was launched more than five years before. That same month, a UNHCR report slammed the Bush administration for their unwillingness to assist refugees, and gave them an "F" on their report card that rated countries in their efforts to assist. "While the Bush administration and the United Kingdom are busy trying to win the war, they have provided no leadership toward ensuring the rights and well-being of the victims of this war," the report stated.

While my hope of going to Iraq to bring truthful information back to U.S. citizens was only partially achieved, mainstream outlets in Europe and other areas of the world ran, and continue to run, many of my articles. Meanwhile, U.S. censorship remains largely intact. The national television and radio appearances I have made in countries like England, Ireland, Italy, Denmark, Qatar, Sweden, China, Japan, South Africa, Canada, Greece and Turkey had no equivalent in the United States. Internet and independent media outlets remain the primary sources in my home country.

I believe that if the people of the United States had the real story about what their government has done in Iraq, the occupation would already have ended. As a journalist, I continue to hold out hope that if people have knowledge of what is happening, they will act accordingly. If people in my country could hear the stories of life under occupation and put themselves into the Iraqis' stories, they would understand. I hold that hope because the stories of Iraq are our story now. Whether we accept that or not, it is the truth. The water from the Euphrates runs through all our veins.