Romero’s 40 years of death

looks at what Night of the Living Dead and George Romero's other zombie classics have to say about U.S. society.

"THERE ARE two types of people in the world," a friend of mine once said, "those who get zombie movies, and those who don't."

My friend and I both love zombie movies, and conversely don't understand people who don't "get" them. My friend was talking about the modern zombie genre--which is characterized by bloody "gags" (heads exploding, intestines being eaten, chewing on human arms as if they were turkey legs) as well as social criticism and satire.

Early zombie movies were something else entirely. They were chock full of colonial ideas based on wildly misinformed and racist prejudices. Take for example, the 1932 film White Zombie, starring Bela Lugosi as the "voodoo master" of (Black) Haitian zombie slaves.

The modern zombie genre began in 1968 with George Romero's low-budget black-and-white masterpiece Night of the Living Dead. Romero continued the genre he created in the four decades that followed with Dawn of the Dead (1978), Day of the Dead (1985) and Land of the Dead (2005).

The DVD release of Romero's latest zombie flick, Diary of the Dead (2008), provides an opportunity to review those 40 years of death.

In 1968, with a crew of friends and colleagues from Pittsburgh (where he worked on local television ads as well as on Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood of all things) Romero headed to rural Pennsylvania to make the movie that turned zombie films (and horror movies more generally) upside down.

It was this film that created the "rules" of the zombie genre--which are often broken, but provide the baseline for understanding elements of future horror films as widely divergent as 28 Days Later and Zombie Honeymoon.

Some social catastrophe (often of unknown origin) has suddenly animated the recently dead, causing them to murder the living and feast on their flesh, creating an ever more widely expanding army of the undead--resulting in what amounts to a zombie apocalypse. A horror genre in which society becomes an (apparently) unthinking army of walking death is pregnant with potential for social criticism.

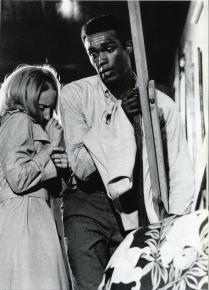

Night of the Living Dead was born out of the political strife of the 1960s. For example, the hero of the film, Ben (played by Duane Jones) was Black. Romero has insisted that he didn't cast Jones for political reasons but because he was the most qualified actor he knew. This in itself would have been political in the filmmaking world of 1968.

But when Night of the Living Dead was released, it became a cult sensation, with millions reading into the film elements of the Black liberation struggle (and state repression against the struggle) as well as the barbarism of the U.S. war in Vietnam.

As Elliot Stein wrote in the Village Voice, Romero's movie "was Middle America at war, and the zombie carnage seemed a grotesque echo of the conflict then raging in Vietnam. In the first-ever subversive horror movie, the resourceful Black hero survives the zombies only to be killed by a redneck posse."

As Romero recalls, the political impact of his movie began to sink in as he drove the footage to New York City for editing. He heard on the radio the news of Martin Luther King's assassination--which would soon be followed by the largest wave of mass urban uprisings in U.S. history.

When the credits roll in Night of the Living Dead, images flash of sheriff deputies led by German shepherds (just like those in Bull Conner's Birmingham) and men with meat hooks dispassionately pilling up corpses into bonfires.

TEN YEARS later, Romero returned to the genre he created with a sequel to Night of the Living Dead--the original Dawn of the Dead, famously set inside a massive indoor suburban shopping mall.

Romero got the idea while touring an actual shopping mall development in Pennsylvania:

They had these sealed-off rooms upstairs packed with civil defense stuff, which they had put there in event of some disaster--and that's what gave me the idea. I mean, my God, here's this cathedral to consumerism, and it's also a bomb shelter just in case society crumbles.

Unlike the 2004 remake, Romero's version is a far funnier (dead people have trouble using escalators for example), more grotesque and more political film--and like Night of the Living Dead, it bears the marks of the political time in which it was made.

The film takes aim at what Romero sees as an increasingly empty consumerism that is failing to compensate for the social disintegration marked by the economic crises of the 1970s and the beginning of a rightward shift of politics that would be the hallmark of the 1980s.

Romero's most depressing zombie movie is easily his 1985 film, Day of the Dead--meant as a critique of the stultifying politics and militarism of Ronald Reagan's reheated Cold War. The movie takes place in a retooled missile silo where a group of scientists (including a genuine mad scientist) and soldiers (including a megalomaniac commanding officer) study the undead looking for a way to kill, control or cure the undead.

The most sympathetic character in the movie is not even a human being--but a zombie named "Bob" who learns how to use tools and even a gun. Eventually the zombies take over the silo and kill almost everyone--except for a scientist and two helicopter pilots who escape to a deserted island.

Romero's original script called for an even more explicitly anti-militarist plot in which armies of the undead were forced by army scientists to fight each other--but costs put such a movie out of reach.

It would be 20 years before Romero returned to the zombie genre in 2005 with Land of the Dead--his only zombie movie with a large Hollywood budget. Land of the Dead takes aim at both growing economic inequality and George Bush's "war on terror." A corrupt businessman (played by Dennis Hopper) has taken control of an armed outpost of survivors in the ruins of Pittsburgh--from which raiding parties are sent out to gather supplies.

Within the outpost, the rich live in a luxurious high-rise, replete with a shopping mall and fine dining--while the poor live in slums. The class divisions within the outpost are mirrored by the violence of the raids on the zombie-infested towns beyond the outpost.

A raid on "Union Town" goes bad, an army of zombies follows the raiding party back to Pittsburgh, attacks the outpost, and more or less abolishes class distinctions by eating most of the rich people in town.

ROMERO'S LATEST film, Diary of the Dead--largely critical of the mass media--is his first movie that returns to the beginning of the zombie apocalypse since Night of the Living Dead. It is also his least successful zombie movie--bearing a weakness found in his dead series, a certain amount of moralizing. Usually, however, his movies are artistically good enough to more than make up for this weakness.

In Dawn of the Dead, for example, the storytelling, character development, and groundbreaking zombie effects outweigh Romero's deep-seated (and occasionally annoying) belief that "we" are all collectively to blame for society's problems (and by extension the social catastrophe of the walking dead).

Still, Diary of the Dead isn't a bad movie. It begins with a news report (that was never aired) about the murder-suicide of an immigrant couple and their son. Their corpses come back to life and attack the police, medical workers and reporters on the scene.

You quickly learn that the cameraman posted the video on the Internet after it was suppressed (either by the government or the television station). A false news report was planted instead that it was an attack by "illegal aliens."

The footage is incorporated into a film student's documentary, Jason Creed's The Death of Death--shot for the most part on two hand-held cameras--that makes up the bulk of Diary of the Dead.

All the moralizing in the narration voice-over (done by one of the characters)--for example: "are we really worth saving?"--mars a lot of the movie.

The problems with Diary of the Dead flow out of the problems with the way Romero views the politics in his movies. As he protested once, "I'm not trying to preach, or ask questions. Well, maybe ask questions, but certainly not answer any questions."

The problem is, of course, that this is an answer of sorts. All the right things outrage George Romero, but he sees no solution to the social catastrophe he sees all around him. In his movies, in the end, there is no real way out of the zombie apocalypse. There is hiding--in a shopping mall, a missile silo, a farmhouse or a safe room--and there is escape--to Canada (he seems to like the idea of escaping to Canada) or to a deserted tropical island.

But there is no way to stop the horror of living death.

But you can't judge Romero on this alone. His movies are products of their time--and the last four decades have seen a great deal of catastrophe, but only recently glimmers of hope.

Moreover, at his best, Romero knits together a critique of society into interesting (and often humorous) dramas that reflect the mundane horror of everyday life in a society that millions secretly fear is already one of living death.