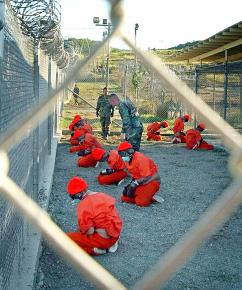

What’s next after Guantánamo?

In the wake of Barack Obama's executive order to close down Guantánamo, explains what his actions mean--and don't mean.

AS ONE of his first acts as president, Barack Obama issued an executive order to close the U.S. prison camp at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, within a year.

The same executive order affirmed that current detainees have the constitutional right to habeas corpus--having their cases heard in U.S. courts--something the Bush administration repeatedly denied and fought to prevent.

In a second executive order issued the same day, Obama revoked Bush administration policies on interrogations, and instructed that prisoners be treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions while being questioned by U.S. officials.

Many people see the closing of Guantánamo as a vindication of the change that Obama promised during the election campaign. The prison camp stands as a potent symbol of the worst abuses of the Bush administration and its "war on terror"--torture, indefinite detention and the shredding of civil liberties.

Right-wingers, however, had a different reaction. "The president makes two moves that could bring terrorists to the U.S.," reported Fox News. Republican House Minority Whip Eric Cantor warned, "I think the first thing we have to remember is that we're talking about terrorists here...Actively moving terrorists inside our borders weakens our security. Most families neither want nor need hundreds of terrorists seeking to kill Americans in their communities."

This is nothing but fear-mongering--and it accepts as necessary the Bush administration's appalling policy of detention without any rights at Guantánamo and a system of military kangaroo courts.

BUT THERE are omissions and inconsistencies in Obama's actions that should concern anyone who cares about human rights.

For example, as journalist Allan Nairn pointed out, Obama's executive order on interrogation has a loophole. It only applies to the treatment of prisoners "in the custody or under the effective control of an officer, employee or other agent of the United States Government, or detained within a facility owned, operated or controlled by a department or agency of the United States, in any armed conflict."

That formulation would allow the use of torture by other governments' security forces operating on orders from the U.S.--under, for example, the "extraordinary rendition" program used by the Bush administration to evade the law by farming out the torture of "war on terror" prisoners to U.S.-allied regimes.

Beyond this, Obama's actions are framed in a way that wholeheartedly accepts the ideological justification of the "war on terror."

For example, as his executive order notes, the closing of Guantánamo is being done in order to further U.S. foreign policy and national interests, not out of a recognition of the fundamental rights of detainees.

The same logic was on display during the confirmation hearings for Eric Holder, Obama's choice for attorney general. Holder told senators that he regards waterboarding as torture (something that retired Adm. Dennis Blair, Obama's nominee for director of national intelligence, of which the CIA is a part, refused to say). As AlterNet's Liliana Segura noted:

Holder's headline-generating answer on the question of waterboarding--which he bluntly labeled torture--deserved a certain amount of praise, especially given recent memories of the preposterous testimony by Alberto Gonzales a few years back...

But Holder also made it clear that he believes we are living in dangerous times, and thus his first goal will be to "strengthen the activities of the federal government and protect the American people from terrorism." "Nothing I do is more important," he said. "I will use every available tactic to defeat our adversaries, and I will do so within the letter and the spirit of the Constitution."

In fact, during the hearings, Holder took a page out of the Bush administration playbook, asserting that enemy combatants could be held in detention as a preventative measure "for the duration of a conflict"--which, Segura wrote, "in the context of the 'war on terror' is a direct threat to habeas corpus and due process." Segura added:

When asked whether prisoners at Guantánamo who might not be convicted could nevertheless be kept in U.S. custody due to the belief that they still pose a threat to the United States, Holder left the possibility open. "There are possibly many other people who are not going to be able to be tried but who nevertheless are dangerous to this country," Holder said. "We're going to have to try to figure out what we do with them."

Also disappointing to many activists are indications from the new White House that it won't seek to prosecute Bush administration officials who knowingly sanctioned torture.

Although Obama did take the step of revoking Bush's executive order making presidential records secret for up to 12 years after leaving office (a necessary step if prosecutions were to happen), according to the Associated Press, in a story that quotes anonymous administration officials, "there's little--if any--chance that the incoming president's Justice Department will go after anyone involved in authorizing or carrying out interrogations that provoked worldwide outrage."