Tragedy strikes back at home

was deployed to Iraq with the Army's 10th Mountain Division and is a member of Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW). In March 2007, he helped start IVAW's first active-duty chapter and became a dedicated antiwar activist.

Here, he reports on the growing epidemic of suicides among veterans of the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

IN THE early morning hours of October 20, 2008, Pfc. Timothy Alderman took his own life in his barracks at Fort Carson, Colo. He died of an apparent prescription drug overdose.

The 21-year-old had been stationed in the Iraqi city of Ramadi. Before his long deployment to the Middle East, he had never suffered from any mental health problems. In fact, according to his medical records, he didn't think he would have difficulty returning home because he "mostly had fun killing people and getting paid for it."

But like hundreds of thousands of other veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, Alderman left the battlefield, but the battlefield didn't leave him.

He began struggling with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the medical condition that has become the signature wound of the U.S. "war on terror."

According to an investigative series by Salon.com's Mark Benjamin and Michael de Yoanna, Alderman sought help from his chain of command upon his return, but was met with demeaning comments from his company sergeants, such as, "I wish you would just go ahead and kill yourself. It would save us a lot of paperwork."

On October 13, only a week prior to his suicide, Alderman joined a small group of soldiers in writing sworn statements about their experiences in Iraq. In his statement, he describes dealing with repeated nightmares about a February 2007 combat experience in which he pulled the dismembered corpse of a fellow soldier from a vehicle that had been hit by a roadside bomb.

"I am seeking help, but I feel like I'm not being treated right," wrote Alderman in the statement. "I mean mental help. I struggle every day with it."

Though the Army has ruled his death a suicide, there is another possibility: Alderman may have died as a result of a lethal interaction of the many powerful drugs prescribed to him by Army medical personnel because of his mental condition. According to Benjamin and de Yoanna:

On discharge, records show, doctors had Alderman on 0.5 mg of Klonopin for anxiety, three times a day; 800 mg of Neurotin, an anti-seizure medication, three times a day; 100 mg of Ultram, a narcotic-like pain reliever, three times a day; 20 mg of Geodon at Noon and then another 80 mg at night, as a treatment for bipolar disorder; 0.1 mg of Clonodine, a blood pressure medication also used for withdrawal symptoms, three times a day; 60 mg of Remeron, for depression, once a day; and 10 mg of Prozac twice a day.

Alderman is also reported to have taken Xanax and morphine.

Though the Army is quick to dismiss his death as yet another tragic case of suicide, evidence suggests that there was negligence by his caregivers in identifying and treating his symptoms properly.

In fact, Benjamin and de Yoanna contacted an Army psychiatrist to ask about the list of drugs and dosages Alderman was taking. "Oh God," the psychiatrist replied. "That's shitty. That breaks all the rules. He was overmedicated. That's bad medicine."

As evidence for declaring Alderman's death a suicide, the Army points to a letter that Alderman pinned to his wall, addressing his deceased mother. But according to Alderman's military friends, the letter didn't read like a suicide note.

Regardless of whether it was a suicide or accidental death, one conclusion is inescapable: the military could have done much more to ensure that Alderman was taken care of when he returned home.

Alderman's former roommate puts responsibility for Alderman's death squarely on the military. "I know he didn't commit suicide," he told Benjamin and de Yoanna. "I don't think he should have been released from the hospital. I know for a fact the Army killed my friend. I want something done. The Army is killing people left and right, and nobody cares."

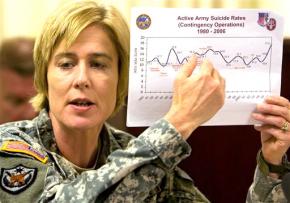

ALDERMAN WENT on some 250 combat missions in Iraq and had 16 confirmed kills, according to members of his unit. Now, he is one of 128 soldiers who committed suicide in 2008. According to the Army's own statistics, this is the highest suicide rate for soldiers in three decades.

There are several barriers that veterans like Alderman face when seeking help for combat-related mental health disorders.

First, there's the stigma. Even when the symptoms of trauma are crystal clear, a soldier who acknowledges such an issue must confront the conflict between seeking help and the constant pressure within the military to send soldiers to the battlefield. Already, many soldiers have been sent on multiple deployments, and especially in the macho culture of the military, mental health issues generally aren't considered serious enough to warrant real attention.

Then, there are worries about admitting to a mental health disorder because it might affect a future promotion.

There has also been widespread negligence by the military in providing adequate health care, especially mental health care, for soldiers. Whether it is failing to recognize and treat PTSD, or overmedicating soldiers who suffer from stress or injuries, the trauma associated with war has created a crisis for veterans who are not receiving proper care when they return home.

The Veterans Administration, which deals with health care for veterans when they are discharged from the military, has not been any less negligent than the military when it comes to dealing with suicides and treatment for trauma.

Both the military and VA have failed to put adequate resources into addressing the huge needs that active-duty personnel and veterans have as the U.S. enters the eighth year of its "war on terror."

As one example, some 300,000 veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, nearly one in five, suffer from major depression or PTSD upon returning home, but only about half of them seek treatment--at least in part due to the long wait times for appointments with doctors and other therapies.

According to a CBS News report last April, the head of mental health for the VA, Ira Katz, said the following in an internal VA email regarding suicide attempts by veterans:

Shh! Our suicide prevention coordinators are identifying about 1,000 suicide attempts per month among veterans we see in our medical facilities. Is this something we should (carefully) address ourselves in some sort of release before someone stumbles on it?

Speaking on the record in November 2007, however, Katz told CBS News, "There is no epidemic in suicide in the VA." But if 1,000 veterans a month attempting suicide is not an epidemic, then what is?

Katz's duplicity is chilling--not only for the veterans who are already enrolled in the VA, but also for soldiers who are being ordered to Iraq and Afghanistan today, and are likely to return home to a mental health system even more overburdened than it is currently.

IN OCTOBER 2006, Spc. Zach Choate, who served as a scout with the Army's 10th Mountain Division in southern Baghdad, was riding in his vehicle on a combat patrol when a roadside bomb detonated, ejecting him from the gunner's turret. After returning to the U.S. for treatment, he was awarded the Purple Heart. He was also diagnosed with PTSD.

After receiving his military discharge, he waited seven months for his disability claim to go through. This was after waiting more than a year to get his medical records back from the military. He now regularly receives treatment at the VA Hospital in Atlanta where he says his problems with PTSD are not being adequately addressed.

"The only questions my doctor asks me to identify how I am doing with PTSD is whether I am suicidal and how I am medicating," he said in an interview. "It seems like she is not properly trained to deal with my issues."

For most veterans, the transition from military health care to the VA is already the hardest transition that they face. Along with the waiting time for a disability claim to be approved, there is also the trouble associated with injured veterans who did not serve two full years in the military. Without two years of service, a soldier is not eligible for VA care, no matter what their injury from combat may be.

This policy jeopardizes the well-being of veterans who are being sent to Iraq and Afghanistan immediately after finishing basic training.

With the Obama administration taking over in Washington, hopes are higher than ever that veterans will be taken care of when they come home. This is especially true after the glaring failures of the Bush administration, which even opposed improving education benefits for veterans because it feared that GIs might then leave the military in order to go to college.

But with the escalation of wars overseas and the economic crisis at home, the money needed to take care of veterans will not be allocated without veterans and civilians alike making this a central demand from the new administration. Putting force behind the demand "Money for jobs and education, not for war and occupation" is essential if veterans are to get the benefits they deserve.