The road to Harper’s Ferry

On October 16, 1859, a small band of men, led by the radical abolitionist John Brown, attacked the federal armory at Harper's Ferry, Va. The group hoped to strike a spectacular blow against a government that upheld the horrific institution of slavery, and to spark a wider uprising against the slave power in the American South.

The attack was defeated--the raiders were besieged and Brown captured by a U.S. Army unit led by future Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. But John Brown's raid wasn't a failure. The great abolitionist Frederick Douglass disagreed with Brown's plan, but wrote of its ultimate impact: "If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery...Before this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain."

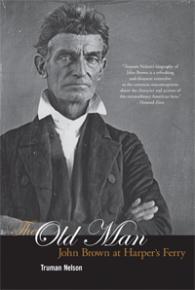

In The Old Man (that was Brown's nickname), narrates the events at Harper's Ferry, with both a historian's grasp of the issues that formed the backdrop to the raid, and a novelist's eye for detail and character. Now the book has been republished by Haymarket Books.

Here, with permission, we reprint part of a chapter from The Old Man that describes John Brown's clandestine meeting with Frederick Douglass in the hopes of persuading him to join the Harpers' Ferry raid.

AT CHAMBERSBURG, the Old Man had gone to earth in an abandoned quarry west of the town. There he could remain in concealment for days, as gray and monolithic as the uncut granite all around him. Although Douglass was to be his most important recruit, he again followed the rules of the classic coup by not telling Douglass how far he intended to go until he had agreed to come along or had given evidence of firm commitment.

The Old Man had known Douglass since late in the 1840s when the latter visited him while he was living in Springfield, Massachusetts. Douglass had just completed a tour of the West for the American Anti-Slavery Society, speaking two or three times a day, and was utterly exhausted by the abuse he had endured. The windowpanes of the hall in which he lectured had been smashed, and he himself had been pelted with rotten eggs and garbage, struck by stones and sticks, and insulted with filthy outcries of "Nigger, go home." While riding on trains or stagecoaches, he was forcibly ejected from any seat a white man wanted. He was not allowed to come to the table while any white man sat there and sometimes went for days without a decent meal while whites feasted sumptuously before his eyes.

Through all this, the American Anti-Slavery Society, which employed Douglass, told him to confine his resistance to the truths that all men are brothers and are enemies only through misunderstanding one another. He was warned that any physical action on his part might bring about an actual war between the blacks and whites in which the blacks, a tiny, unarmed minority, would be slaughtered.

Douglass, wondering how much longer he could stand this physical abuse, went to see some outspoken militants of his own race, Henry Garnett, J.N. Gloucester and J.W. Leguen. They insisted that it was not true that all whites would combine against them if the blacks took up guns. They told him about a group John Brown had organized in Springfield called the League of Gileadites, in which this white man had joined with forty-four black people in an agreement to arm themselves "in case of an attack on any of our people." The American people, Brown told them, would be more impressed by the personal bravery of the black man than by the peaceful recital of his wrongs, however truthful: "Nothing so charms the American people as personal bravery. The trial for life of one bold and to some extent successful man, for defending his rights in good earnest, would arouse more sympathy throughout the nation than the accumulated wrongs and sufferings of more than three millions of our submissive colored population."

Douglass left a description of the Old Man as he first saw him: "He was lean, strong, and sinewy, built for times of trouble, fitted to grapple with the flintiest hardships. Clad in plain woolens, shod in boots of cowhide, he was straight as a mountain pine. His eyes were gray and were full of light and fire. He moved with a long, springing, racehorse step, neither seeking or shunning conversation."

Since the two men met first at Brown's wool establishment, a prosperous-looking business, Douglass thought Brown was wealthy, but when he went to the Old Man's home, he found it a small and simple abode, such as lived in by poor folks. Brown told him money saved by this way of life was to be put into the struggle for black liberation. After a frugal meal, Brown began to talk with Douglass, the pacifist, with a blunt honesty such as the black man had never met with before from any white man. Brown told him he thought the slaves should gain their freedom in any way they could, that the slaveowners had forfeited their right to live, and that neither political action nor nonviolent pleadings and demonstrations could abolish the oppression of the blacks.

Brown told Douglass he had been looking for a long while for black men he could join with in a plan of guerrilla warfare. They would hide themselves in the Allegheny Mountains where they run off to the Deep South. A body of black and white guerrillas, by the use of natural forts, could stand off all attackers and conceal large numbers of liberated slaves until they were trained to carry out wider and wider forays of slave liberation. Brown insisted that he knew these mountains well, as a practical shepherd and a surveyor, and if bodies of guerrillas would swoop down on the slave plantations, it would no longer be possible for the planters to operate with slave labor.

In this way the money value of slavery would be completely wiped out, and the institution along with it. Douglass wanted to know how he would support these fighters, and Brown answered promptly, "We will live off the enemy." He argued that slavery was a state of war and that slaves deserved all their master's property, having earned it through generations of toil. When Douglass suggested the slaveowners might be peacefully converted to freeing their slaves, Brown replied with some heat, "I know their proud hearts; they will never give up until they feel a big stick around their heads."

Douglass was not ready to join the Old Man. "To get this plan in operation, money and men, arms and ammunition, food and clothing were needed," Douglass wrote later, "and these, from the nature of the enterprise, were not easily obtained, and nothing immediately was done. Captain Brown, too, notwithstanding his rigid economy, was poor, and was unable to arm and equip men for the dangerous life he had mapped out. So the work lingered until after the Kansas trouble was over."

However, Douglass's life was profoundly changed by this encounter. The next time he was attacked by a mob, he took a stick and hit back. Shortly after, he broke away from the nonresistant Garrisonians, moved to Rochester, New York, and started a paper known as The North Star. In one of its earliest issues he wrote about John Brown, "who, although a white man, is in sympathy a black man, and is deeply interested in our cause as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery." During the next twelve years they met briefly from time to time, and Douglass had been involved in getting the Old Man out to Kansas, which, as Douglass said, "left him with arms and men, for the men who had been with him in Kansas believed in him, and would follow him in any humane though dangerous enterprise he might undertake."

THE OLD Man felt that he and Douglass were of the same mind about the Kansas troubles and that a judicious and compelling argument for the attack on Harper's Ferry could be based on them. "I approached the old quarry very cautiously," Douglass later wrote, "for John Brown was generally well armed and regarded strangers with suspicion. As I came near, he regarded me rather suspiciously, but soon recognized me and received me cordially." It was no wonder the Old Man had a light lapse of recognition; instead of the fierce young lion-headed Douglass of the previous decade, he saw a stately and rather portly gentleman of great distinction, moving with the dignity of an ambassador of his race.

Douglass had with him a stalwart young black recruit, Shields Green, who had been attracted to the Old Man when they met in Rochester. The first moment was awkward, however. "Well, Captain," Douglass began, "when I reached Chambersburg a good deal of surprise was expressed, for I was instantly recognized, that I would come there unannounced. I was pressed to make a speech to them, with which invitation I readily complied."

The Old Man had an expression on his worn, anxious face that indicated that public speaking at this juncture was not the best of tactics. "He was then under the ban of the government and heavy rewards were offered for his arrest, for offenses said to have been committed in Kansas," Douglass remembered. "I felt that I was on a dangerous mission and was as little desirous of discovery as himself...although no reward was offered for me."

Kagi, on guard high on the rocks in a place of concealment, came down, carrying his Sharps, and the four of them, Douglass, Shields Green, Kagi, and Brown began to discuss plans and possibilities. The conversation lasted the rest of that day and half of the next. The Old Man announced triumphantly that he was at Chambersburg to pick up two hundred new Sharps carbines, two hundred revolvers, and almost a thousand pikes, with which to empower those who would nobly dare to be free. Douglass began to reminisce about the time the Old Man had appeared before the Convention of the Radical Political Abolitionists in June of 1855.

The Convention, a remnant of the defunct Liberty Party, was deep in a discussion of affairs in Kansas.

Kansas was the place where the fault in the American earth--that it was "half-slave, half-free," as Lincoln put it--first broke through at the surface and American citizens confronted one another with arms in their hands and an unbridgeable gulf between them. One hundred and twenty-six thousand square miles of virgin soil, it had been Indian Territory until 1855, and was then opened for settlement. Americans began to confront one another over the question of slavery with guns in their hands and Congress tried to stave off open warfare between these systems with a so-called organic law by which the actual settlers would vote in a plebiscite to make it either a free state or a slave state.

Douglass wrote, "the portentious shadow of a stupendous civil war became more and more visible."

Slaveholders complained bitterly that they were about to be despoiled of their share in a territory won by common warfare, or bought by a common treasure. However, the rapidly growing antislavery (but not abolitionist) party in the North insisted that southerners could settle in any part of the Union, along with their "property," so long as "property" was not interpreted to mean men and women. Declaring that the Founding Fathers had not intended the extension or the perpetuity of slavery, they hammered out a slogan for their new Republican Party: Liberty, National; Slavery, Sectional.

The idea of a plebiscite is always politically attractive, and when it was announced, Douglass advocated thousands of free blacks be sent to Kansas to colonize and "stand as a wall of living fire" to keep slavery out. Once the blacks were in Kansas, he argued, "armed with spades and rakes and hoes and other useful implements of defense, they need not be driven out."

At the time of the plebiscite, however, five thousand southerners, armed to the teeth, pushed across the Kansas border on horseback or in wagons, occupied all the polling places, and terrorized the election officials into accepting their ballots, although most of them returned to Missouri the following day. The new government of Kansas became proslavery; the Territorial Legislature passed a law making the advocacy of antislavery a capital crime, punishable by hanging, and both a territorial judiciary (appointed by the proslavery National Administration) and the highest officials of the Administration itself gave notice that the new Territorial Legislature was to be backed to the hilt by all the enforcement powers at the government's command.

After the Border Ruffian invasion was sanctioned by the Democratic Administration, Douglass realized that it was almost impossible even for white northerners to settle in Kansas. They were damned as "abolitionists" and harassed by roving bands; their cabins were burned and looted, their fences torn down, their crops trampled, and their cattle run off. Finally, as Emerson put it, when "the poor plundered farmer comes into the courts, he finds the ringleader who had robbed him, dismounting from his own horse and unbuckling his knife to sit as judge."

Douglass, whose mind had a superb, statesman-like quality, did not agree with other black leaders who felt that the Kansas struggle was irrelevant to them; a white racist struggle between the northern speculators and the slave expansionists. "The important point to me, as one desiring to see the slave power crippled, slavery limited and abolished, was the effect of the Kansas battle upon the moral sentiment of the North, how it made men abolitionists before they themselves became aware of it, and how it rekindled the zeal, stimulated the activity, and strengthened the faith of our old antislavery forces."

He was not surprised to see the Old Man turn up at this 1855 Abolitionist Convention, and to learn from him that five of his sons had gone to Kansas to settle, to help swing the Territory to an antislavery position. The Old Man asked Douglass if he could make an appeal to the Convention for money to buy arms. When this was arranged, Douglass found opposition among many of the members, who had long deplored John Brown's reputation for wanting to solve the question directly with violence and revolution. But when the Old Man got up to speak, his worn face lit from within by long-banked fires, the audience was completely won over and subscribed more than sixty dollars to buy the guns. He read a letter sent him by his son, John, Jr.:

Dear father...I tell you the truth when I say that while the interest of despotism has secured to this cause hundreds and thousands of the meanest and most desperate men, armed to the teeth with revolvers, Bowie knives, rifles, and cannon--while they not only are thoroughly organized, but under pay from slaveholders--the Friends of Freedom are not one fourth of them half armed, and as to Military Organization, among them, it no where exists in the territory. The result of this is that the people here exhibit the most abject and cowardly spirit whenever their dearest rights are invaded and trampled down by lawless bands...They boast that they can obtain possession of the polls in any of our election districts without having to fire a gun...Now the remedy we propose is that the Anti-slavery portion of the inhabitants should immediately, thoroughly arm and organize themselves in military companies. Here are five men of us who are not only anxious to fully prepare, but are determined to fight. Now we want you to get for us arms. We need them more than we do bread.

Sitting there amongst the grim, inhospitable rocks, the Old Man was heartened by Douglass's recollections of the Convention, since it seemed to pave the way for the delicate process of recruitment. His whole plan depended on people's remembering and approving his deeds in Kansas. He patted Douglass affectionately on the shoulders and said, "Now it is yourself, Frederick, that we need more than bread."