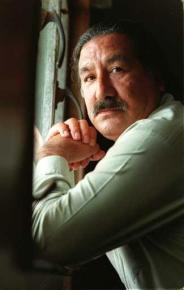

Freedom denied again for Leonard Peltier

examines the federal authorities' politically biased decision to keep political prisoner Leonard Peltier behind bars.

THE U.S. Parole Commission has once again denied parole to American Indian activist and renowned political prisoner Leonard Peltier. After languishing in prison for 33 long years for a crime he did not commit, Peltier has been condemned by the U.S. government to remain behind bars for at least 15 more years.

In 1977, Peltier was sentenced to two consecutive life terms for the deaths of two FBI agents, Jack Coler and Ronald Williams, who were killed in a gunfight on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota on June 26, 1975 in what is known as the "incident at Oglala."

Peltier did not kill the agents--a fact that the U.S. government has not disputed for years. At an appellate hearing in the 1980s, the U.S. attorney conceded: "We had a murder, we had numerous shooters, we do not know who specifically fired what killing shots...we do not know, quote unquote, who shot the agents."

Given this concession, the continued denial of parole for Peltier is awful enough. But federal officials didn't stop with that. The commission set a "reconsideration hearing" for Peltier--in which he will get another chance to plead for parole--in the year 2024. Given his grave health issues, Peltier is unlikely to live until then.

FBI official Thomas Harrington had the nerve to gloat that Peltier deserves to remain in prison because he "demonstrated a complete disrespect for human life and for the law." Indeed, there has been an ongoing smear campaign against Peltier for years, led most notably by former FBI agent Joseph Trimbach.

In reality, the FBI's flagrant abuse of the law--both in the circumstances that surrounded Peltier's case and during his trial--is the real crime.

During the 1977 trial, the U.S. government relied on suppressed evidence, used perjured testimony and even fabricated evidence in order to exact revenge for the deaths of Coler and Williams.

In the years that followed, the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled, "There is a possibility that the jury would have acquitted Leonard Peltier had the records and data improperly withheld from the defense been available to him in order to better exploit and reinforce the inconsistencies casting strong doubts upon the government's case."

But the court system has refused to grant Peltier a new trial.

PELTIER'S FREEDOM--either via parole or clemency--would validate what his family, friends and supporters have argued for over three decades: that Leonard's prosecution and conviction were due solely to his involvement in the American Indian Movement (AIM) in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

AIM led struggles for justice for Native Americans around the country, including a series of high-profile actions such as the 1972 takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington, D.C., and perhaps most famously, the 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973.

These struggles exposed the treacherous conditions of racism and deep poverty faced by American Indians--particularly in places such as the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, where people fought against the corrupt and thuggish rule of tribal president Dick Wilson, who ran the Guardians of the Oglala Nation (known as the GOONs).

Federal officials and Wilson's GOONS launched a vicious attack on Wounded Knee. Some 500,000 rounds of ammunition were fired into the camp. In the wake of the occupation, AIM was targeted by both the FBI, through its murderous COINTELPRO program against radicals, and a local "reign of terror" carried out by Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) police and GOONs.

Between 1973 and 1976, the per capita murder rate on Pine Ridge was the highest in the country--170 per 100,000 people, or around 20 times the U.S. average. This was the context of the famous "incident at Oglala."

On June 26, 1975, two unmarked cars chased a red truck onto the Jumping Bull property on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Across the field from the road was the compound where the Jumping Bull family lived, and where AIM members and their families had set up camp. When the agents, who hadn't identified themselves, began firing on the ranch, Peltier and others, who were defending the compound against violence, fired back, not knowing who the men were or what they wanted.

Within minutes, more than 150 FBI SWAT team members, BIA police and GOONs had surrounded the ranch. The two FBI agents, as well as one Lakota man, Joe Killsright Stuntz, were killed. To this day, no one has been convicted of Joe Stuntz's death.

The largest FBI manhunt in history followed, culminating in the murder charges against Peltier, Bob Robideau and Dino Butler. Robideau and Butler were acquitted in 1976 in an embarrassing defeat for the U.S. government. This is why U.S. officials went after Peltier with a vengeance in his separate trial--and why they have such a stake in keeping him in prison.

But ever since Peltier was put behind bars, his supporters in the U.S. and around the world have waged a campaign to free him. In recent months, large numbers of people signed petitions and wrote letters in support of parole. On July 28, people traveled for a vigil and rally outside of the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pa.

THE DENIAL of parole is a devastating blow to Leonard, his family and the millions of people around the world who have demanded Leonard's freedom. While Leonard's supporters are no strangers to disappointment, many felt they had reason to be optimistic this time.

As the Leonard Peltier Defense-Offense Committee put it on its Web site:

[F]rom the time of Peltier's conviction in 1977 until the mid-1990s--according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice--the average length of imprisonment served for homicide in the United States ranged from 94 to 99.8 months (about 8 years). Even if you were to take Peltier's two consecutive life sentences into account at the higher end of this range, it is clear that Peltier should have been released over a decade ago.

On that basis alone--according to the due process and equal rights protections of the U.S. Constitution--Leonard Peltier should immediately be released.

Peltier has met all the requirements for parole, in addition to maintaining a model prison record. In addition, he is almost 65 years old, in poor health and in need of quality, specialized medical attention.

What's more, Peltier's parole hearing took place in a new political climate. President Barack Obama is no stranger to Peltier's case. Many Peltier activists supported Obama for president in part due to the promise he made to the Crow Nation while campaigning last year.

"I know what it's like to not always have been respected, or to have been ignored, and I know what it's like to struggle," Obama said then. "And that's how I think many of you understand what's happened here on the reservation. That a lot of times you have been forgotten. I want you to know that you will never be forgotten--you will be on my mind every day that I am in the White House."

But American Indians need more than sentiment and reassurances from Obama. A broader struggle to free Leonard will need to be mobilized in order to win--and that means pressuring Obama to act.

In the late 1990s, activists forced former President Bill Clinton to publicly discuss the possibility of freeing Peltier through executive clemency. Instead, Clinton bowed to FBI pressure to deny clemency for Peltier--instead extending his generosity to the likes of multimillionaire crooked businessman Marc Rich.

President Barack Obama has the power to grant executive clemency. But for this to happen, the movement to free Leonard Peltier will need to be galvanized and take a more visible form. The potential for this certainly exists--and people can take their cues from Leonard's fighting spirit.