Myth of the liberal lion

Ted Kennedy's political career reflects the course of American liberalism, from its heyday in the 1960s to its sorry state today.

FOR DECADES, Ted Kennedy was the bogeyman used by conservatives in their fundraising appeals to raise millions of dollars. To them, the liberal Kennedy seemed to represent everything they hated--there was no easier way to get a right-wing crowd booing and hissing than to mention Kennedy's name.

So it was more than a little jarring to hear conservatives sing Kennedy's praises for his "bipartisanship" in the wake of Kennedy's death from brain cancer on August 25.

"There is nobody else like him," Republican Sen. Judd Gregg told the Associated Press. "If he had been physically up to it and been engaged on this [the current health care reform debate], we probably would have an agreement by now."

Yeah, right.

But the Kennedy that the right both demonized for being a liberal icon and praised for his willingness to "reach across the aisle" was one and the same. And the media punditocracy's assessment of him--a doctrinaire liberal turned bipartisan dealmaker--says a lot about what they consider the most important part of his legacy.

With a virtual guarantee of re-election every six years in the overwhelmingly Democratic state of Massachusetts, Kennedy compiled a consistently liberal voting record, with little fear that Republicans would be able to mount a serious challenge to him.

Kennedy went through a series of personal scandals that might have led to jail time for a less politically connected man--from leaving the scene of an accident on Chappaquiddick Island, Mass., that killed a young female campaign volunteer in 1969, to his entanglement with his nephew who was charged with rape in 1991. But none of it put his re-election in doubt.

"[Kennedy] once said that 'I define liberalism in this country'...and he really did for a whole half century, " presidential historian Michael Beschloss told MSNBC's Keith Olbermann on Countdown. Along the way, Kennedy played a key role in redefining and redirecting liberalism and its chief standard bearer in the U.S. political system, the Democratic Party.

Fundamentally, Kennedy's political career is a chronicle of the decline of American liberalism, which once promised to end poverty in America, but now debates whether including even a mild "public option" in a health care reform bill might be a bridge too far.

TED KENNEDY was the youngest child of the wealthy Kennedy dynasty that dominated Democratic politics in the post-Second World War era.

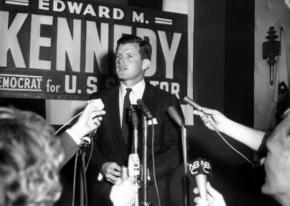

He was elected to the Senate at age 30 in 1962 when one of his brothers was president and the other was attorney general. The New York Times decried this as an example of dynastic politics "demeaning to the dignity of the Senate and the democratic process." Even Kennedy himself later conceded that the Times had a point.

He came to Congress as a standard-issue Cold War liberal. Through most of his first term in the Senate, he lined up with the northern wing of the party, then riding the liberal high tide of the Kennedy-Johnson years. Kennedy supported the creation of Medicare and Medicaid, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the War on Poverty.

He was also a loyal vote to fund the Vietnam War. He broke with the Johnson administration's pro-war position only in 1967, not long before his brother Robert launched his challenge to Lyndon Johnson in opposition to the "unwinnable" war.

The Kennedy-Johnson years were a time of economic expansion, when liberalism spoke of creating a "Great Society" of equality and opportunity. Kennedy's role in 1965 as floor leader to push through changes in immigration law abolishing quotas by national origin reflected this. In a time of economic boom and low unemployment, anti-immigrant voices were marginalized.

At that time, Kennedy stood in the mainstream of the Democratic Party, along with fellow senators Walter Mondale and George McGovern, who could be counted as reliable votes for legislation endorsed by civil rights organizations and the AFL-CIO. But Kennedy's signature issue was health care.

In the early 1970s, Kennedy and Rep. Martha Griffiths of Michigan supported the creation of a government-run "single-payer" system to make health care a right for every American. Kennedy and Griffiths ran into opposition from Republican President Richard Nixon and business organizations.

Kennedy abandoned his own bill in 1974 and later supported legislation that preserved the role of the private insurance industry in the health care sector. "My feeling is that this is the central cop-out of liberal leadership," long-time single-payer advocate Dr. Quentin Young said in an interview with Socialist Worker in 2003. "Ted Kennedy was the author of an excellent single-payer [universal insurance] bill of 1971. But now, since it's not considered feasible, they don't even push for it."

Kennedy's willingness to give up on big plans in exchange for incremental half-measures was emblematic not only of his adaptation to the back rooms of the U.S. Senate, but also of a larger shift in the ambition and scope of liberalism as it began to feel the assault of the conservative ascendancy of the 1970s.

Within a few years, not only was a strengthened Republican Party readying the neoliberal attack on the gains of the 1960s, but conservative politics began to influence the mainstream of the Democratic Party. The policies that later became known as "Reaganomics"--austerity for the poor, pro-business tax cuts for the rich, and deregulation--actually got their start during the ill-fated Democratic administration of Jimmy Carter, with an assist from Ted Kennedy.

As Lee Sustar wrote in Socialist Worker:

It was Kennedy who called for deregulation of the airline and trucking industries as early as 1974, two years before Carter was elected. "[Kennedy] won Carter to the cause in the 1976 campaign and ultimately gave the president the issue," the Boston Globe noted...The consequences of Kennedy-sponsored deregulation are still being felt in the series of airline bankruptcies today and the virtual deunionization of the trucking industry.

Pro-business Kennedy staffers Alfred Kahn, who became a guru of deregulation under Carter, and Stephen Breyer, now one of the more pro-business justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, pioneered these policies. Breyer also promoted, as far back as 1979, the idea that forms the core of today's "climate change" legislation--using a market in "pollution credits" to address environmental damage.

KENNEDY WASN'T as conservative as Carter, or as the next neoliberal Democratic President Bill Clinton. In fact, Kennedy mounted a failed liberal challenge to Carter for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1980. He denounced Clinton's 1996 "welfare reform" bill abolishing Aid to Families with Dependent Children.

But once the "liberal lion" Kennedy endorsed a free-market policy like deregulation, it made it easier for other more conservative Democrats to go along with the Republicans as the GOP proceeded to move U.S. politics to the right. Kennedy even voted for the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings bill imposing mandatory budget cuts in 1985.

As much as right-wing politicians demonized Kennedy, they were happy to have his support when it came their way. "Even Ted Kennedy is for it..." became a punch-line for conservatives seeking to win support for their retrograde policies. "Teddy was the only Democrat who could move their whole base," right-wing Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch told the Associated Press. "If he finally agreed, the whole base would come along, even if they didn't like it."

After George W. Bush stole the White House in 2000, he made a point of wooing Kennedy on two of his chief domestic policy initiatives--the No Child Left Behind education law, passed in 2001, and the Medicare prescription drugs benefit, passed in 2003. Both of these laws have become Trojan horses for continued privatization, union-busting and corporate welfare.

That may not have been Kennedy's intention as he rounded up liberal support for these bills, but it certainly was George Bush's and Karl Rove's. This raises the question of what Kennedy thought he was doing when he was negotiating with such dishonest brokers.

Even if Kennedy could claim that Bush and Rove snookered him on these pieces of legislation, he couldn't say the same about another bipartisan initiative that loomed over the last few years of his life--the immigration reform bill he crafted with Republican Sen. John McCain. In fact, Bush and Rove--and big business--looked to the Kennedy-McCain bill as an outline for their own position on immigration reform.

Despite the fact that millions of immigrants and their supporters marched to demand legalization for all of the undocumented in 2006 and 2007, the Kennedy-McCain bill would have codified a massive "guest worker" program and increased "border security." Kennedy himself continuously made the case that his bill didn't amount to an "amnesty" for the undocumented.

Although it fell far short of the real demands of immigrants and their families, Kennedy-McCain came to be seen as the only "realistic" legislation on offer. In the event, though, even Kennedy-McCain wasn't conservative enough for anti-immigrant Neanderthals in the Congress, and it went down to defeat.

It's this Ted Kennedy--the one who put ideological ideals aside to cut bipartisan deals--who the political media has celebrated so much since his death.

Over his Senate career, Kennedy cast over 15,000 votes. Many of those votes were in favor of expanding services for the poor, the elderly, children and the disabled, and rights for workers, immigrants, racial minorities, women, and gays and lesbians--or against eliminating them. He described his 2003 vote against authorizing "this misbegotten war" in Iraq as "the best vote I have cast."

But we shouldn't forget that--as a mainstream politician who mastered the Washington game of logrolling and back-scratching--Ted Kennedy also enabled policies that have devastated the lives of the ordinary people for whom he claimed to fight.