Insurrection at Harper’s Ferry

On an October day 150 years ago, a small band of men, led by the radical abolitionist John Brown, attacked the federal armory at Harper's Ferry, Va. The group hoped to strike a spectacular blow against a government that upheld the horrific institution of slavery, and to spark a wider uprising against the slave power in the American South.

The attack was defeated--the raiders were besieged and Brown captured by a U.S. Army unit led by future Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. But John Brown's raid wasn't a failure. The great abolitionist Frederick Douglass disagreed with Brown's plan, but wrote of its ultimate impact: "If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery...Before this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain."

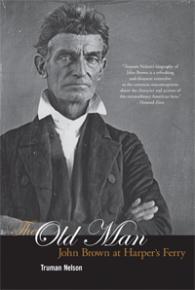

In The Old Man (that was Brown's nickname), narrates the events at Harper's Ferry, with both a historian's grasp of the issues that formed the backdrop to the raid, and a novelist's eye for detail and character. Now the book has been republished by Haymarket Books. Here, with permission, we reprint part of a chapter from The Old Man that describes John Brown's Harper's Ferry raid getting underway.

Whereas Slavery, throughout its entire existence in the United States, is none other than a most barbarous, unprovoked and unjustifiable War of one portion of its citizens upon another portion; in utter disregard and violation of those eternal and self-evident truths set forth in our Declaration of Independence...We, Citizens of the United States, and the Oppressed People, together with all other people degraded by the laws thereof, do, for the time being ordain and establish for ourselves, the following Provisional Constitution.

-- John Brown, Preamble to the Provisional Constitution

THERE WERE nineteen men going down that road to Harper's Ferry in the thick damp and mizzling dusk of an October night, nineteen men ready to take on the slavery and tyranny of the state of Virginia. Their aim was to confront the slaveholding South in such a way that either it went down, or they did. Three men were left behind to guard the arms and meet unknown supporters; Owen Brown, who had a withered arm; Francis Meriam, who had a missing eye; and Barclay Coppoc, so young and untried it seemed as if his mother should be giving him orders instead of John Brown.

They all knew what they had to do, at the moment and in the larger plan of the new state with its Provisional Constitution. Later, people would say that it was all unclear, but the men most concerned understood very well.

The Old Man was driving the wagon, wearing his "Kansas cap," a peaked cap with earlaps hanging down given him by an Ottawa Indian leader. It symbolized for him the continuity of his struggle. In the wagon were twenty pikes, a crowbar, a sledgehammer, and some pine fagots and bundles of tow for incendiary purposes. It was five miles to the Maryland end of the Potomac Bridge; Brown's company walked two by two down the rutted dirt road. It was chilly, and they wore gray shawls which were folded over their Sharps carbines. Cook and Charles Tidd went first; they were to cut the telegraph wires to Washington and Baltimore on poles just outside the bridge.

Before they entered the long, dark cavern of the covered bridge, Brown ordered them to fasten their cartridge boxes outside their shawls and to cock their carbines. John Kagi and Aaron Stevens moved in a half trot to the Virginia end of the bridge as the others paused at the entrance. A watchman came toward them with a lantern in his hand, alarmed by their bustling motion. They held him, and told him that he was their prisoner but that no harm was intended to him. Stevens took the watchman's lantern and waved it in a wide arc to tell Brown and the others it was safe to enter. The watchman, unperturbed, stood quietly until Cook and Watson Brown came along, cradling their Sharps guns in their arms. He began to laugh when he saw the blond, long-haired Cook trying to look threatening. Even with his Sharps gun, two revolvers in his belt, and the swagger of a pirate on his quarterdeck, he was unconvincing.

As the wagon entered the dark cavern of the bridge, the hoofbeats of the little horse echoed with a slow and steady timber, like drumbeats for marching men not now on parade. Sitting above the steady, even clop, clop, clop, clop, the Old Man tried to fix himself into a pace of thought and action that would be as even and deliberate. He must not hurry, make snap judgments, or show panic in any way. The action should be done with revolutionary decorum, with a decent respect for the opinions of mankind. He made another little prayer. "Please God, our Father, make it so there will be very little blood."

His head ached and his hands, trembling slightly on the reins, reminded him of the irreversible ills that years had accumulated. It was now or never; the twenty-four hours ahead would be the climax of his life. Everything he had ever read about revolution, about the classic coup, had to be remembered now.

THE SLOW plod through the pitch-black darkness of the bridge was oppressive. But at last he could see ahead the arcing glint of a lantern, signaling all's well. There were no shots, no outcries of hurt and death. So far the passage to the trial by fire was favoring him.

The watchman at the bridge was laughing until he saw the Old Man come up. Then he stopped. Coming out of the bridge, the men trotted, almost frolicking, after long days penned up in the farmhouse attic. The bridgehead emptied people and trains into a kind of public square. To the right as the travelers came out was, first, the train depot joined to a hotel called the Wager House. On the left was a shoddy saloon known as the Galt House. Straight ahead was an impressive three-story building where the completed guns were stored. To the right again, just beyond the hotel, was John Brown's target area, the Government Armory. This was the setting for the impending drama--all within a scale of sixty paces.

The first act of violence against the United States took place at the Armory Gate. It was locked shut. Tidd and Aaron Stevens tried to force it open. Daniel Whelan, a watchman in the United States service, was in the watchhouse, which was in the third bay of a brick building known as the Engine House because two of the bays held the arsenal fire-fighting equipment. Brown wanted to use this stout building as headquarters. Whelan, hearing the wagon rattling over the cobblestones of the square, and then stop, came out of the watchhouse, shouting: "Hold on!" He walked over to the gate, and he saw the men, wrapped in gray shawls and carrying deadly weapons; some of them were already leaping over the fence, filled with the alertness and energy that a dangerous mission releases in trained fighters.

Whelan had to tell his story many times, officially and otherwise. It never changed, and has the ring of truth: "I told them I would not open the gate, and one of them jumped on the pier of the gate over my head, and another fellow ran and put his hand on me and caught me by the coat and held me. I was inside, and they were outside and the fellow standing was over my head upon the pier. And then when I still would not open the gate for them, five or six ran in from the wagon, clapped their guns against my breast and told me I should deliver the key. I told them I could not, and another fellow said they had no time to be waiting for a key, to go to the wagon and bring out the crowbar and large hammer. They went to the little wagon and brought a large crowbar out of it. There is a large chain around two sides of the wagon-gate going in. They twisted the crowbar in the chain and they opened it. And in they ran. One fellow took me. They all gathered about me and looked in my face; I was nearly scared to death with so many guns about me. I did not know the minute or hour that I would drop. They told me to be very quiet and make no noise, else they would put me into eternity. The wagon was marched in. Brown dispatched all the men out of the yard, but he left a man at each side of the gate, along with himself. He, himself, had me and Bill Williams [the other guard], and then he said, 'I came here from Kansas, and this is a slave state. I want to free all the Negroes in this state. I have possession of the United States Armory now and if the citizens interfere with me, I must only burn the town and have blood.'"

The battle stations to which the men were dispatched had been carefully planned. Two were to be at each bridge. Three were to occupy the arsenal standing outside the grounds, but near enough for protective cover in a firefight; and another company, under the command of Kagi, was to take over Hall's Rifle Works, about a half-mile up the river on Shenandoah Street. This move was a very chancy one; it separated effective fighters from the main force and tied up Kagi, who was second in command to Brown and the best thinker among the liberators.

But the Old Man's overriding compulsion was to prevent bloodshed. He felt that keeping the thousands of guns at Hall's out of the hands of the counter-attackers was worth the very great risk of extending his men so far from the center of control. The men there would be fighting not to expand the area of battle, but to contain it.