Our lawyers, but not our law

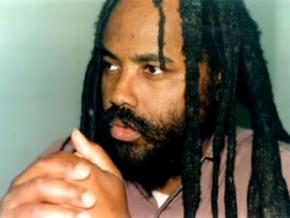

reviews the newest book by prisoner-activist Mumia Abu-Jamal.

"PETITIONER CAN not make any pretense of being able to answer the learned Attorney General of the State of Florida because the petitioner is not an attorney or versed in law nor does not have the law books to copy down the decisions of this Court. But the Petitioner knows there is many of them. Nor would the petitioner be allowed to do so."

These are the words of Clarence Earl Gideon, a homeless man with an eighth grade formal education, decrying the fact that he had been denied the right to a lawyer at trial. And yet Gideon went on to train himself in the prison law library, appealing to the Supreme Court on his own behalf.

His handwritten, impeccably argued appeal sparked the landmark Gideon vs. Wainwright, the 1963 case that established the fundamental right of a criminal defendant to legal council. It's a lesson worth absorbing: The only reason defendants even have a right to professional representation is because of one prisoner's advocacy on his own behalf.

One can watch Law and Order five nights a week and see prisoners depicted only as villains or, at best, victims passively assisted by professionals. Mumia Abu-Jamal's new book Jailhouse Lawyers reminds us that today--with a prison system so enormous and unwieldy that one in every 100 U.S. citizens is incarcerated--often the only legal advice available to those on the inside comes from other prisoners, schooled in the law by necessity and interested in helping out of basic solidarity.

This phenomenon isn't just a curiosity--as the book notes, some of the most fundamental prison reform litigation has had its origin behind bars. The heart of Jailhouse Lawyers, fittingly, is a series of case studies telling the stories of these figures.

The cases range from the humble to legendary. They include an anonymous woman whose advocacy overturned a paternalistic New Jersey Department of Corrections decision preventing a fellow prisoner from marrying. The book dedicates an entire chapter to issues faced by female prisoners, the fastest-growing section of the prison population.

The book also tells the stories of jailhouse litigators like David Ruiz, whose skillfully crafted civil rights complaint against the Texas Department of Corrections forced fundamental changes in that state's plantation-style prison system.

GIVEN THE role of jailhouse lawyers in exposing injustices, it's not surprising that they have come under attack. Abu-Jamal points to a study that found that, of all groups within prisons, "no segment of the modern American prison population--not Blacks nor gays not AIDS patients nor gang members--outweighed jailhouse lawyers when it came to prisoners who were targeted but the prison administration for punishment."

Ruiz, for instance, was flung into solitary confinement for launching his complaint. "It is telling that those who, for the most part, are the most studious of prisoners, those who are most apt to use pen and paper--rather than, say, a 'lock in a sock'--to address and resolve grievances, are the most targeted of all prison populations."

But the assaults haven't just come on the inside. The law-and-order mania of the last few decades has been accompanied by an assault on jailhouse lawyers. The so-called Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) of 1995 severely restricts the kinds of issues prisoners can litigate. Proponents of the PLRA sold the bill by citing anecdotes of frivolous lawsuits, mainly tall tales that Jailhouse Lawyers skillfully unmasks.

And yet its consequences have been dire. As Abu-Jamal points out, following the act, the kind of torture displayed in the Abu Ghraib photos, "if committed in an American prison, would have been insufficient for a judge or jury to award damages, for the Prison Litigation Reform Act signed by President Bill Clinton does not allow recovery for psychological or mental harm or injury."

For Abu-Jamal, ultimately, the significance of jailhouse lawyers is that they point to a fundamentally different way of relating to legal matters, based on class solidarity. As he points out, "street lawyers, by their very nature, have a state-created space, a bar so to speak, that effectively distances them from their clients."

Yet he is aware, throughout this book, that even putting aside various issues of concern--the use of jailhouse lawyers as snitches, incompetent jailhouse lawyers--there is danger in becoming too invested in fighting in the courts. The law, he reminds us, is a tool of the powerful. As Steve Evans, another jailhouse lawyer, says in the book: "That's they law; it ain't our law, dude."

Finally, Abu-Jamal agrees with Ed Mead, cofounder of Prison Legal News: "The main thing is to put jailhouse lawyering in a context of class struggle. And when you put it in that context its limitations become abundantly clear." Truly fighting the prison system means building social movements, and Jailhouse Lawyers looks to the civil rights movement and revolutionary politics for inspiration in this regard.

Mumia says very little about his own case in this book (though those familiar with his case will know that the fact that he was denied the ability to represent himself at trial is a fundamental issue). As this is published, there is once again an organized campaign to try to execute him, with a new anti-Mumia film, The Barrel of a Gun, funded by Philadelphia GOP honcho Kevin Kelly, set to debut in December, and a new Philadelphia DA who has publicly sworn to make his death sentence a reality.

New activists looking to understand the issues that have made this case an international symbol of the anti-death penalty struggle should see Mumia Abu-Jamal: A Case for Reasonable Doubt? and In Prison My Whole Life, two acclaimed documentaries, and read J. Patrick O'Connor's recent The Framing of Mumia Abu-Jamal.

And then they should read Jailhouse Lawyers to remember that Mumia Abu-Jamal is not just the victim of shocking injustice, but also, as Angela Davis says in her introduction to the book, "one of the most important public intellectuals of our time."